32-C Maine Antique Digest, May 2015

- AUCTION -

earliest mechanical timekeepers.

At three and a half pounds is the

Patrizzi & Co. May 24, 2009, hardcover

auction catalog of “Pre-Pendulum Euro-

pean Renaissance Clocks.” This sale, also

a single-owner collection, was auctioned

in Milan, Italy. It benefited from the con-

sultations of horological expert Philip

Poniz, a friend who also has worked with

Sotheby’s and Antiquorum. He kindly

provided observations on several of the

Christie’s lots. I chatted with him during

the preview as he was closely examin-

ing one of the lots, and after the sale he

e-mailed me to add, “Clients and friends

bought a considerable number of them.

I will be busy restoring them for a long

time.”

Philip Poniz’s four-page introduction

to the Patrizzi & Co. catalog provides

an excellent overview of the history of

mechanical timekeeping and the impor-

tance of these early clocks, beginning in

the early 14th century. He equates their

significance with combustion engines

and computers. This history is far too

complex and lengthy to summarize here,

but the Guggenheim clocks also provide

a short introduction to the subject.

Several thick volumes of Sotheby’s

multipart sale of the Time Museum col-

lection also contribute to my bookshelf

sag. Three of the Christie’s lots (59, 78,

and 98) had been in that disbanded muse-

um’s collection that was sold off more

than a decade ago.

At another Sotheby’s sale, “The Justice

Warren Shepro Collection of Clocks” on

April 26, 2001, a circa 1720 English table

clock sold for $19,150. As lot 77 at Chris-

tie’s, it was passed at $11,000, well below

its $20,000/30,000 estimate. Although the

prestigious name Daniel Quare appears

on the dial, the auctioneer announced that

the clock was in the “manner of Daniel

Quare,” clearly halving its value.

The weightiest volume, at nearly

seven pounds even in softcover, is the

Italian-language exhibit publication

La

misura del tempo; L’antico splendore

dell’orologeria italiana dal XV al XVIII

secolo

. The 2005 show in Trento, Italy

was mounted and cataloged by Italian

horology expert Giuseppe Brusa. I deeply

regret not traveling to view the show, but

I can peruse the book’s 669 pages to view

detailed material on Italian clockmaking,

which made many early contributions to

the science. A lengthy English review

was prepared by Fortunat Mueller-

Maerki, another friend and colleague,

who chairs the Library Collections Com-

mittee of the National Association of

Watch & Clock Collectors.

Fortunat Mueller-Maerki attended the

Christie’s sale. He noted that there were

few clock people among the small audi-

ence and that phone and international

Internet bidders were the norm. I too saw

the auctioneer address online bidders in

California, Belgium, Spain, Germany,

Denmark, and Singapore. Although For-

tunat made no purchases, preferring to

spend his money on horology books and

ephemera, he commented on a disturbing

evolution. Fewer major auction houses

have regular specialty clock auctions or

related catalogs available to subscribers.

Except for the occasional strong col-

lections, clocks mainly appear singly in

furniture and decorative arts sales, where

they are difficult to locate and track. This

may then reinforce the idea that clock

people are not a good target group and

that fewer resources should be devoted

to that category and to experts who can

accurately assess and estimate values of

old clocks.

The situation is very different for vin-

tage watches, a hotter collectible with

their own auctions and expert teams.

However, some auction houses such as

Skinner and Bonhams do continue with

concentrated clock sales, perhaps mixed

with watches, scientific instruments, and

vintage technology. The trend may bene-

fit lower-tier horology auctioneers, such

as R.O. Schmitt Fine Arts, that cater spe-

cifically to clock and watch enthusiasts.

Toby Woolley, Christie’s head of clock

department, is based in London and has

been with the firm for nearly 25 years,

specializing in furniture and decorative

arts. He has been its clock director since

November 2011. He enjoys the multi-cen-

tury range of clocks, unlike other special-

ties that are confined to shorter periods.

He kindly escorted me through the pre-

view, offering additional information

and a few looks inside and under the gilt

cases. He never met Peter Guggenheim

but revealed that there was no question

that Christie’s would get this consign-

ment. From a dealer friend of mine who

knew Guggenheim well, I was told that

Guggenheim and Abbott sold their entire

collection of antique French furniture

when they moved out of New York City

and that Christie’s ably handled that sale

for them.

By my calculation, the total for the 50

sold clocks was $4,352,125. Of the nine

not meeting reserves, two are most worth

describing. Lot 78, passed at $48,000, had

been sold as lot 166 at Sotheby’s on June

19, 2002, in part two of the sale of theRock-

ford, Illinois, Time Museum collection.

This miniature English ebonized time-

piece could not reach its $70,000/100,000

estimate. Its early 18th-century London

maker, Samuel Watson, was a maker of

complicated astronomical clocks and had

several pages devoted to him in Cedric

Jagger’s 1983 book

Royal Clocks: The

British Monarchy and Its Timekeepers,

1300-1900

.

Lot 114 passed at $100,000, not close

to its $200,000/300,000 estimate. This

miniature English table clock had been

from the David Arthur Wetherfield col-

lection of clocks dispersed in 1928. By

the time Wetherfield died that year, he

had accumulated 232 fine English clocks

that filled his home in Blackheath, South

London. Perhaps his best was Thomas

Tompion’s William III towering long-

case clock, now at Colonial Williams-

burg. The passed lot, only about 6" tall

and made circa 1740 by Richard Peck-

over of London, was number 49 in a 1981

comprehensive book about the Wether-

field collection by British horologist Eric

Bruton. The clock also had Metropolitan

Museum of Art provenance as number 53

in the 1972 exhibit, and it is shown as fig.

97 in the R. W. Symonds 1986 edition of

Masterpieces of English Furniture and

Clocks

.

As a full-time restorer and seller

of antique clocks, I always am asked

whether an old clock runs and “keeps

good time.” This is a reasonable question

for factory-made clocks from the 19th

and 20th centuries. I do my best to keep

these antique machines running 24/7,

even after millions of ticks and bongs,

although I believe that Seth Thomas and

all those other makers would be amazed

that people still are attempting to use

clocks, really “appliances,” that they

manufactured 100 or 200 years ago. Cer-

tainly in the year 2115 there will be no

televisions or washing machines or SUVs

made today that anybody still will be try-

ing to use.

There was absolutely no mention of the

running condition of any of the clocks in

the Christie’s sale, nor in any other of the

exhibit and sale books and catalogs that

I have referenced. While collectors may

attempt to operate these ancient time-

keepers on occasion, and to have them

professionally restored by Philip Poniz

and the few others capable of this level of

work, the value of these clocks is in the

history, art, and craftsmanship they repre-

sent, not in whether they can tell the same

time as on your wrist, wall, or phone. Just

as the Smithsonian does not fly the

Spirit

of Saint Louis

nor the U.S. Navy sail the

U.S.S.

Constitution

out into the middle

of the Atlantic Ocean, these centuries-old

clocks deserve to rest and bask in their

glory, not to risk further deterioration and

damage. Except for a few running exam-

ples that are carefully maintained and

monitored, most museums and collectors

adhere to this concept.

Fortunately, I heard nobody at the pre-

view loudly asking why the clocks were

not ticking and keeping time. In a very

real sense, they still are keeping time.

For more information, contact Chris-

tie’s at

(www.christies.com).

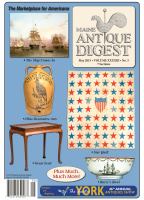

Bacchus may be drowning his sorrows for

selling under the $120,000/180,000 estimate

at $112,500. Made by one of two Kreitzers

of Augsburg, Germany early in the 17th

century, the clock has a later base, which

may have restrained bidding. The drink-

er’s eyes moved with each tick, and his

right arm hoisted the bottle to his mouth

every hour. This was number 27 in the 1972

Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit and

number 98 in the 1980 Smithsonian show.

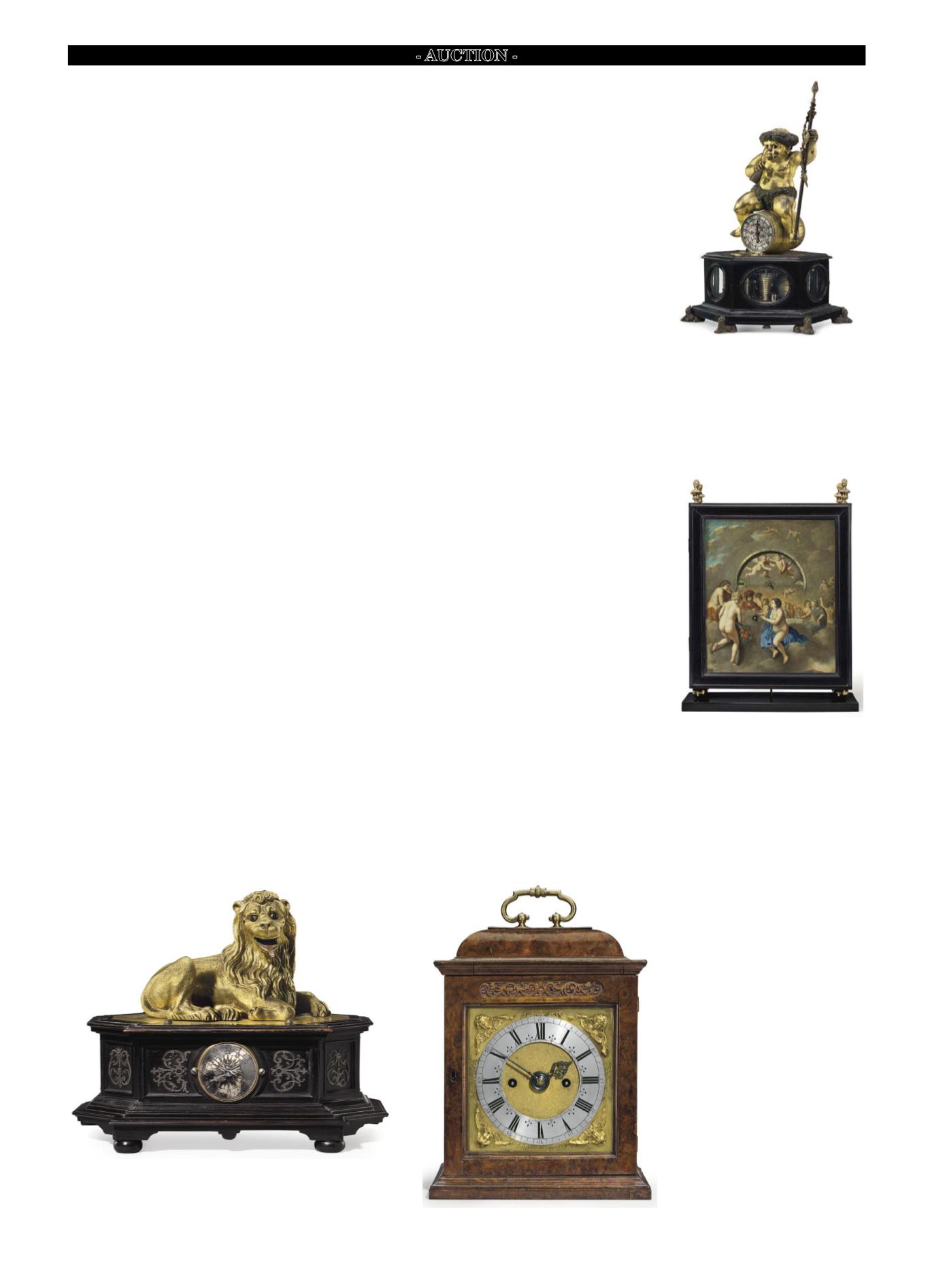

The English clocks in the sale were of uneven

appeal, but this circa 1685 London table clock by

Joseph Knibb exceeded, with premium, its high

estimate when it sold for $221,000. The maker’s

prominence in English clockmaking history and

the clock’s unusual “double-six” striking con-

tributed to the strong price. Designed to extend

mainspring power, “double-six” counted the

hours only from one to six, then started over.

Most of us could figure out that six dings in

the middle of the day or night actually signals

twelve o’clock, but obviously the concept did not

catch on.

Another lion automaton with moving eyes, tongue, and jaw on each hour,

this Augsburg German gilt-metal and ebony clock, circa 1630, was one

of the few selling to a room bidder. Number 28 in the 1972 Metropolitan

Museum of Art exhibit, here it sold for $155,000. The silvered dial shows

24 hours.

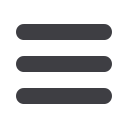

Two Dutch clock experts, whom I recently

visited in the Netherlands, both extolled

this ebony wall clock, 1680-90, by Pieter

Visbagh of The Hague. According to Hans

van den Ende, only three such examples

are known, and this one’s finials and

feet are French and later. Its revolving

chapters, indicating the time, are inte-

gral with the dial painting of a Bacchic

feast. The artwork, signed “C.P.,” could

be by well-known Dutch artist Cornelius

van Poelenburgh or one of his students,

Cornelis Palmer, said to have used the

same initials. The clockmaker succeeded

Salmon Coster, who made the first pen-

dulum clock for Christiaan Huygens in

1657, and the movement is quite similar

to that original groundbreaking design.

A brief Peter Guggenheim article on this

clock was published in the December 1969

issue of

Antiquarian Horology

, the maga-

zine of the Antiquarian Horology Society

in England, and this clock was pictured on

the cover. The clock, not a “night clock”

with internal illumination although simi-

lar in appearance, also is extensively cov-

ered in Reinier Plomp’s 1979 book

Spring-

driven Dutch Pendulum Clocks, 1657-1710

.

It sold for $62,500.