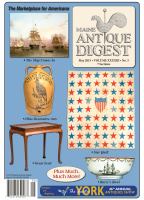

Maine Antique Digest, May 2015 31-C

- AUCTION -

☞

T

wenty-six hours was not too long

to wait. The New York City snow-

storm abated so bidders a day later

could try for clocks rarely available to buy

or even to view in museums. Described as

a “New York Kunstkammer,” the Abbott/

Guggenheim collection, belatedly offered

at Christie’s on January 28, included 59

preindustrial clocks in its 117 lots. The

other lots were equally important sculp-

tures, mostly bronzes, also collected for

decades by Drs. Peter Guggenheim and

John Abbott of Warwick, New York.

Eighty-five lots sold, 50 clocks among

them, for a sale total of $11,454,875.

Guggenheim, a psychiatrist and pro-

fessor of psychiatry, died at age 84 in

2012, survived by his partner of over 60

years, John Abbott, whom he married

in 2007. Related to “the” Guggenheims

(his great-uncle Solomon’s museum is on

Fifth Avenue, and his aunt was Peggy),

Peter received his first clock at age six

and never stopped collecting. He was an

amateur repairer who

amassed and gener-

ously lent a collection

of mostly German

16th- and 17th-cen-

tury

timekeepers,

many with additional

complications, func-

tions, and automation. Such clocks, fab-

ricated by masters working long hours

before mass production and division of

labor, were inaccurate and ornate, costly

and few, owned solely by royalty and the

very wealthy. Other such collections are

unlikely to appear on the market anytime

soon, and now this one has been scattered.

Two iconic museum exhibits had show-

cased many clocks from the collection.

From January 4 to March 28, 1972, the

Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted

Northern European Clocks in New York

Collections

. The thin softcover catalog,

written by assistant curator Clare Vin-

cent, described the show’s 81 clocks, 27

of which belonged to Guggenheim, and

21 of those clocks were in the recent

Christie’s sale. Vincent remains a cura-

tor in the Met’s department of European

sculpture and decorative arts, and she is

preparing another clock exhibit for later

this year. In the Christie’s auction cata-

log’s opening pages, Dr. Klaus Maurice

refers to her as “the female pope of clocks

and watches.”

Maurice had been closely associated

with the other major exhibit,

The Clock-

work Universe: German Clocks and

Automata, 1550-1650

, which graced the

Smithsonian’s National Museum of His-

tory and Technology from November 7,

1980, to February 15, 1981. As noted in

the captions, many Guggenheim clocks

were on view and also were described in

the large related book of the same title

by coauthors Klaus Maurice and Otto

Mayr.

Another smaller exhibit had included

three Guggenheim clocks. From Decem-

ber 18, 1999, to March 19, 2000, at the

Bruce Museum of Arts and Science in

Greenwich, Connecticut,

The Art of

Time

displayed what now became

Christie’s lot 30, selling for

$62,500 (with buyer’s premium).

It is a gilt-brass and ebony German

striking and automaton clock by

Paullus Schiller of Nuremberg,

1620-30, with the figure of the

goddess Urania pointing to the

passing hours. The other two

Guggenheim clocks pictured in

the Bruce Museum booklet were

not in the current sale.

I lent two American

clocks to the Bruce

Museum exhibition,

and although I never

met Peter Guggen-

heim, I may have

been in the same

room with him if he attended the opening

reception at the museum.

Another lender, 19 clocks, to the

1972 Met exhibit was Winthrop “Kelly”

Edey of New York City. This eccen-

tric collector of mainly French Renais-

sance clocks passed away in 1999. He

donated a small but valuable clock col-

lection and a large archive to the Frick

Collection in NewYork City. He authored

two books on French clocks, and I

have been researching his unpublished

writings and notes, which may still be

of use. In his papers, I have seen many

references to Peter Guggenheim as they

collaborated and competed. A 1965 Edey

receipt for a clock purchase noted, in an

unintended admission of auction pool-

ing, that it was “bought jointly by me

and Peter Guggenheim, then auctioned

between us for $11,000.”

The Christie’s catalog weighs in at

more than four pounds, with beautiful

full-color full-page photographs and

detailed listings of features, provenance,

exhibitions, and related literature. It

instantly has become a valuable reference

resource and joins a small number of vol-

umes that constitute most of the available

concentrations of material on these

Christie’s, New York City

Early Clocks, One Day Late:

The Abbott/Guggenheim Collection

by Bob Frishman

Photos courtesy Christie’s

By my calculation,

the total for the

50 sold clocks was

$4,352,125.

The top-selling clock, and second

only overall to a bronze Hercules

that sold for $2,045,000 (see p.

33-C), this 1580-90 German gilt

striking and automaton lion

clock by Philipp Miller went to

a determined phone bidder who

steadily jumped bid increments

until the hammer fell far above

the $150,000/250,000 estimate.

This clock earned $965,000.

The lion’s eyes, jaw, tongue,

and foreleg also would jump

into action as each

hour rang out. It

was number 25

at the 1972 Met-

ropolitan Museum

of

Art

clock

exhibit and num-

ber 90 in the

1980 Smith-

sonian

The

C l o c kwo r k

Un i v e r s e

.

Second-highest clock, and

third-highest lot overall

in the sale, was this

German gilt striking

and

astronomical

table clock from

Augsburg, 1560-70.

Jump bids by the

same phone bidder

as for the top-selling

clock were ultimately

successful,

again

at a multiple of the

$200 , 000 / 300 , 000

estimate. It sold for

$725,000.

Number

13 in the 1972 Met-

ropolitan Museum of

Art exhibit, the clock has

a lengthy description of its

many features and functions in

that exhibition catalog by curator Clare Vincent. It is

number 41 in

The Clockwork Universe

. Philip Poniz

reported that the price is a record for this style and

justified by its remarkably good condition despite a

few later changes to the case.

Sixth in the sale’s top ten

lots, this large Augsburg

German gilt bronze and

brass

quarter-striking

astronomical clock, dated

1625, was maker David

Bushmann’s

master-

piece, required for admis-

sion into the elite guild.

Deservedly displayed at

the preview among paint-

ings, not the clocks and

bronzes, it was described

by Philip Poniz as having

an astonishing state of

preservation except for a

small missing bit of the

top armillary sphere.

Number 30 in the

1980 Smithsonian

The Clockwork

Universe

, it sold

for $569,000.

Toby Woolley, head of Christie’s clock department,

appeared thrilled to be standing with the Bushmann

masterpiece. Based in London, Woolley was in New

York for the preview and sale. Frishman photo.

This circa 1680 month-du-

ration ebony long-case clock

by famed maker Joseph

Knibb had been in the

Wetherfield collection. Eric

Bruton’s book noted several

originality problems typical

of Wetherfield’s clocks that

often were severely restored,

some say “butchered.”

Selling under estimate at

$149,000, theKnibb retained

its waist door sticker from

New York dealer Arthur

S. Vernay, who purchased

nearly half of the famed

English collection. Weth-

erfield had strongly hoped

that all his clocks would

remain in England, not be

sold to “persistent Ameri-

can millionaires,” but we do

not know if the high bidder

is repatriating this example.

One of the few French clocks in the sale, this gilt-brass and copper striking

table clock by Nicolas Plantart is circa 1600 fromAbbeville. It was number 2 in

the 1972 Met exhibit and was pictured and described in Winthrop Edey’s 1967

book on French clocks when it was already in Guggenheim’s collection. Edey

noted that it signified a new square shape, superseding the older hexagonal

form. The engraved illustration portrays Christ meeting pilgrims on the road

to Emmaus. It brought $100,000.