Maine Antique Digest, April 2017 7-D

-

FEATURE

-

-

7-D

Anyone for Quoits?—Not with These Nightmarish Examples!

Lobsters and Luscious Lips Define a Surreal Legacy

I

n his 1818

Memoir of the Late War in

India

, the soldier and military historian Sir

William Thorn (1781-1843) describes the

terrifying impact that the very destructive

weapons known as Chakkar Quoits had on

cavalry.

“Besides the matchlock, spear, the scim-

itar, which are all excellent in their kinds,

some of the Seiks are armed with a very

singular weapon…. It consists of a hollow

circle, made of finely tempered steel, with

an exceedingly sharp edge, about a foot in

diameter, and an inch in breadth on the inner

side.

“This instrument the horseman poises on

his fore-finger, and after giving it two or

three swift motions, to accelerate its veloc-

ity, sends it from him to the distance of some

hundreds of yards, the ring cutting and maim-

ing, most dreadfully, every living object that

may chance to be in its way.”

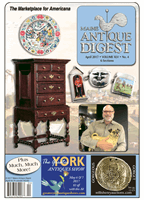

Mounted in a later glazed and velvet-lined

ebony wall cabinet, the three gilded steel

Chakkar Quoits seen upper far right are

of different sizes, the largest 9" (23 cm) in

diameter.

Probably presented as trophies following

the successful conclusion of the Second Sikh

War (1848-49), they were either acquired by

or presented to James Andrew Broun-Ram-

say, Marquess of Dalhousie (1812-1860), for

his arms and armour collection.

Far removed from the quoits that have in

some form or another a very long history but

are probably best remembered as deck quoits

and a game that could be played on the decks of ocean liners to

pass the time on long sea passages, these fearsome weapons were

estimated at around $2000/3000 but sold instead for $39,955 at

Sotheby’s “Of Royal and Noble Descent” sale on January 19.

And now for something completely different, as they used to say

on

Monty Python’s Flying Circus

, a very smart, “German Empire”

cradle that sold for $16,905 in the same sale.

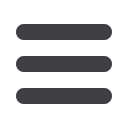

Dated to around 1825, the gilt-brass-mounted, green-painted

mahogany and carved giltwood rocking cradle of boat form seen

below is thought to have been made in Leipzig. The buttoned green

silk upholstery is a later replacement.

No royal or noble pedigree was offered for this lot—though the

craftsmanship suggests that the tiny occupant would have been

well born—but my third choice from the Sotheby’s sale has a

history.

The pair of Queen Anne walnut and marquetry side chairs seen

below are known to have been commissioned,

circa 1705, by Sir John Trevor (circa 1637-1717).

They were initially installed at Trevor House, but

later moved to Powis House in Knightsbridge, and

then in the mid-18th century were removed from London

to the family’s country house, Brynkinalt, in the Welsh

border county of Denbighshire.

Sold for $92,200, they are

believed to have been part of a

suite of furniture in the latest,

fashionable taste commissioned

from the royal chair-makers

Thomas Roberts and his son and

successor, Richard.

Standing on French-inspired

“broken” cabriole front legs and

with exaggerated “hoof” feet, they

show fine seaweed marquetry

inlay work and have needlework

upholstered backs and seats.

The chairs are similar in design

to those in a large suite supplied

by Roberts to Sir Robert Wal-

pole, later 1st Earl of Orford, for

Houghton Hall in Norfolk.

The pair of Queen

Anne side chairs

from Brynkinalt

made $92,200 at

Sotheby’s.

The fearsome Chakkar Quoits sold for $39,955 at Sotheby’s.

This early 19th-cen-

tury German rocking

cradle sold for $16,905.

I

t is a while now, I think, since I included

a telephone in these “Letter from Lon-

don” pages, but a December 15, 2016,

Christie’s sale called “A Surreal Legacy:

Selected Works of Art from the Edward

James Foundation”* prompts me to call

up another—one that was an absolute

must for a Maine-based journal.

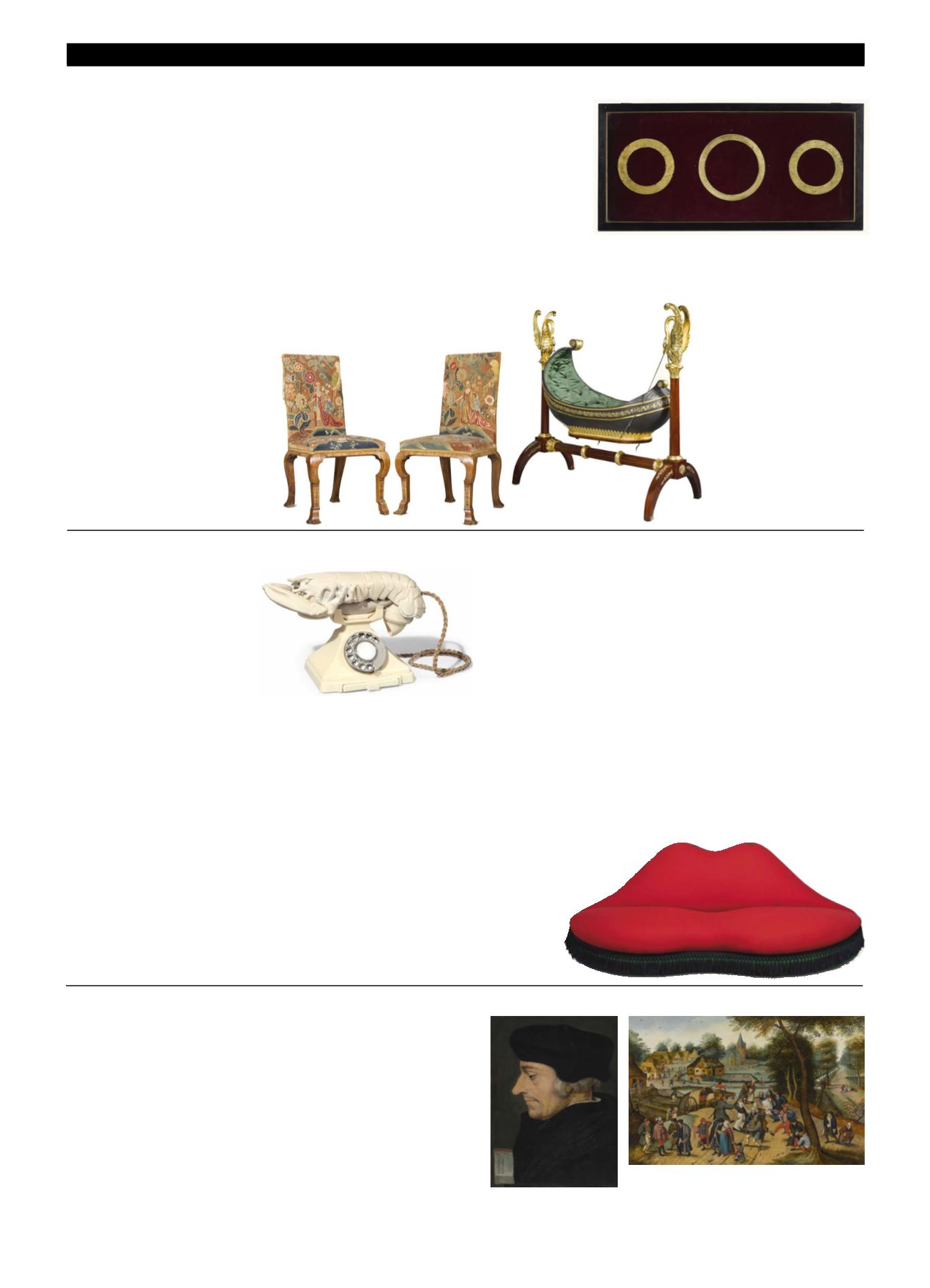

The extraordinary

Lobster Telephone

(white aphrodisiac)

seen here was one of

the creations that resulted from an interior

decorating plan hatched by James and his

friend Salvador Dalí, a plan that would

“…transform the everyday into an eclec-

tic, imaginary environment.”

They collaborated, said Christie’s cata-

loguer, on a range of highly theatrical, sur-

real interior schemes, objects and pieces

of furniture, transforming the rooms of

James’s country home, Monkton, into fan-

tastical Surrealist visions. A sofa became

a pair of scarlet red lips inspired by a

photograph of Mae West, a pair of lamps

was created from a tower of golden cham-

pagne glasses, and a telephone metamor-

phosed into a lobster.

Eleven such “lobster phones” were

commissioned from a London firm, Green

& Abbott, in 1938—seven of which were

white, like the one seen at Christie’s, and

the other four black with red lobsters.

Other examples of that limited lobster run

are now to be found in museums across

the world, among them one in the Minne-

apolis Institute of Art in Minnesota.

Consisting of a white Bakelite tele-

phone with a white plaster lobster shell

encasing the receiver, the idea was seem-

ingly inspired by an event that took place

while Dalí and his lover, Gala, were stay-

ing with James in his Wimpole Street,

London residence in 1936.

James recalled that he, Dalí, and some

other friends were sitting on the bed in his

room eating lobster. When they finished,

these sophisticated but reckless diners

threw the shells off the side of the bed,

one of which, it is said, landed on top of

the telephone.

Amongst other objects to evolve from

James’s fertile imagination and his collab-

oration with Dalí was the Mae West “Lips

Sofa” seen at right.

The initial inspiration for this creation

was Dali’s 1934-35 gouache

Mae West’s

Face which May Be Used as a Surrealist

Apartment

, a deconstruction of a photo-

graph of Mae West in which her facial

characteristics are dismantled and recon-

ceived as furnishing components within

an interior—her lips rendered as a sofa.

In all, five such sofas were made for

James’s own use in 1938. The present

example is one of a pair that was designed

specifically for the dining-room at

Monkton House. Upholstered in bright

red Melton wool fabric, it is principally

distinguished by a heavy black worsted

fringe to the green wool apron, and in

being slightly more elongated than the

other versions.

James’s correspondence with John

Hill of Green & Abbott reveals fastid-

ious attention to this detail—the fringe

was to be specially woven and, accord-

ing to James, needed “…to look like

the embroidery upon the epaulettes of

a picador, or the breeches and hat of a

toreador.”

James subsequently chose to further

ornament this pair of sofas by the careful

positioning to the seat and backs of both

examples of three delicate felt appliqué

shapes, suggestive of caterpillars.

In the London sale, the “lobster

phone” was sold for $1,058,785 and the

Mae West sofa for $908,425, but then

on February 28 that other sofa from

Monkton House turned up in yet another

Christie’s sale, this one drawing on vari-

ous properties and called “The Art of the

Surreal.”

It just edged past the low estimate to

sell at $587,940.

*

As the only son, Edward James, aged

just 25, had inherited the West Dean

Estate in Sussex following the death of

his father, William Dodge James, whose

considerable wealth had originated in

the U.S. copper mining and railroad

industries. More detail on his life (and

this sale) can be found on the Christie’s

website.

Dalí’s

Lobster Telephone (white aphrodisiac)

sold for $1,058,785 at Christie’s.

The Mae West sofa

sold at $908,425.

Familiar and Unrecorded Works by Pieter Breughel the Younger

T

wo very different Breughels are featured here—

both of them the work of Pieter Breughel II, or

“the Younger”—which sold in London old master

sales of last December.

One is a beautifully preserved version of one of

Pieter Breughel the Younger’s most popular compo-

sitions,

Return from the Kermesse

, a merry and bois-

terous band of villagers on their way home from a

country fair. In a December 7 sale at Sotheby’s the

oil on oak panel, just over 19½" x 31", was sold for

$3,256,210—a sum which showed a loss of over $1.3

million for the consignor, who had paid $4,562,500

for the picture in the auctioneers’ New York sale-

rooms in January 2011.

The other, seen at Christie’s on the following day,

is a previously unknown portrait of the great human-

ist scholar and thinker Erasmus—the artist’s only

known portrait of an identifiable sitter.

Erasmus had died some three

decades before Breughel was born

and this little oil on panel, just

under 9" x 6¾ ", appears to be

based on Hans Holbein the Young-

er’s portrait of circa 1523 that now

hangs in the Louvre in Paris, a por-

trait in which Erasmus is depicted

working on his translation of the

Gospel of St. Mark.

That portrait had been sent to

England soon after it was painted,

but while another version was pur-

chased from the artist’s wife in

1542 by Bonifacius Amerbach, a

humanist writer and admirer of Erasmus who lived in Basel, it

seems most likely that Breughel’s posthumous portrait was based

on a Holbein woodcut (after a medal by Quentin Massys) that was

published in Gilbert Cousin’s 1533

Effigies Des.

Erasmi Roterodami

.

Estimated at $50,000/75,000, Breughel the

Younger’s portrait of Erasmus sold at $340,015.