Maine Antique Digest, April 2017 3-D

-

FEATURE

-

-

3-D

Letter from London

by Ian McKay,

<ianmckay1@btinternet.com>

T

his month’s selection contains something a little out of the ordinary in the

form of a heavily illustrated piece on a sale of vesta cases that took place

far from the London rooms—but sales in the capital are certainly not forgotten.

A spectacular ivory table centrepiece known as the “Rothschild Nef,” a trio

of fine English watches, a blooming reminder of the “Tulip Fever” years of

17th-century Holland and a superfast marble Iris are also to be found. Quoits

that served a particularly brutal and bloody purpose are also featured, together

with some “broken” cabriole front legs, while a couple of Breughels also come

into the mix, along with a sprinkling of snowy ski posters.

Also Blooming: A Gravity-Defying, Superfast

Iris

Ivory Nef Pulls Away Once More from a Sotheby’s Shore

Summer Beauty Is a Reminder of Those Long-ago

Days of “Tulip Fever”

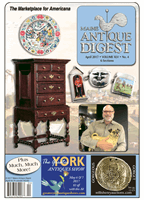

Balthasar van der Ast’s

Zomerschoon

Tulip

was sold for $1.02 million by

Christie’s.

S

ome time has yet to pass before

the tulips start to appear in my

garden, but one special speci-

men deserves a mention before it

becomes a dry, pressed specimen in

my older catalogue files.

Sold by Christie’s for $1,022,575

on December 8 last year, Balthasar

van der Ast’s

Zomerschoon Tulip

,

an oil on panel measuring roughly

10½" x 8", was until fairly recently

thought to date from 1636—but an

earlier date of circa 1625, a time

when the artist was working in

Utrecht rather than Middleburg, is

now thought more likely.

It was in the 1620s and ’30s that

what we now call tulip mania was

rampant in the Netherlands and

absurdly high prices were paid for

new and/or rarely coloured speci-

mens. Fortunes could be made and

lost overnight in an extraordinary

era that was the subject of Debo-

rah Moggach’s 1999 novel,

Tulip

Fever

.

So-called “broken tulips,” those

infected with a virus that resulted

in the sort of variegated colours

seen in this single bloom, were

the most popular new varieties

and the

Zomerschoon

, or Summer

Beauty, usually showing red or pink

streaks on a white or cream petal,

was a highly sought-after variety

that commanded exorbitantly high

prices.

It also remains one of the few

varieties of tulip cultivated in Hol-

land in the 17th century that still

exist today.

To what extent the artist was

influenced by “Tulip Fever” in

his choice of subject cannot now

be known, but something that is

of special significance about this

well-documented picture is its min-

imalist approach.

While the portrayal of single

blooms or plants was common in

watercolours and botanical book

illustration at the time, it was

“highly original for a work in oil”

and this picture was seen as mark-

ing a novel departure in van der

Ast’s work.

Each element of this Summer

Beauty, said the cataloguer, “…is

highlighted by the dark background…

[and] Van der Ast’s expertly applied

glazes of oil paint allow him to ren-

der the subtle modulations of shadow

on the flower, the shine of the round

glass vase and the small, bright high-

lights which distinguish three small

drops of water against the dark leaf

and background.”

This

tulip, it is suggested, is not

merely a flower, but a highly precious

object and one with a veiled, underly-

ing message for the viewer.

“The perfect tulip stands unblem-

ished but will wilt and eventually die

now that it has been cut from its roots.”

The water droplets, one of which is

about to fall from the tulip’s leaf onto

the ledge below, symbolize the tran-

sience of life, and the two insects, it is

suggested, can be regarded as a sym-

bolic representation of man’s eventual

end.

The butterfly (an Adonis blue in this

instance, the lepidopterously minded

will know) was a common symbol of

resurrection and redemption, while the

fly, it seems, was frequently symbolic

of the Devil.

And if all that is too feverish a view,

just think of it as a very nice, but rather

expensive flower picture.

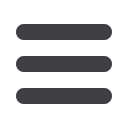

D

escribed by Sotheby’s as “the most

important Italian Romantic sculp-

ture to come to auction in recent years,”

this life-size white marble sculpture of

Iris

, the “Messenger of the Olympian

Gods,” certainly lived up to the billing

when in their December 14, 2016, sale

of 19th- and 20th-century sculpture she

sold for a treble estimate $542,895.

Signed and dated Milan 1873,

Metello Motelli’s

Iris

was said by the

auctioneers to epitomise the ambitious

imagination and technical virtuosity of

Lombard marble carvers in the second

half of the 19th century, and in its exu-

berance and technical accomplishment

should be considered the sculptor’s

masterpiece.

Iris was also seen as a personifica-

tion of the rainbow and was thought to

travel across land and sea at the speed of

wind—qualities depicted so that “…in a

gravity-defying tour-de-force, the god-

dess—personified as a graceful young

girl—is seemingly lifted by a torrent of

foliage and cloth, which, leaning for-

ward, she suspends above her head as a

billowing veil.”

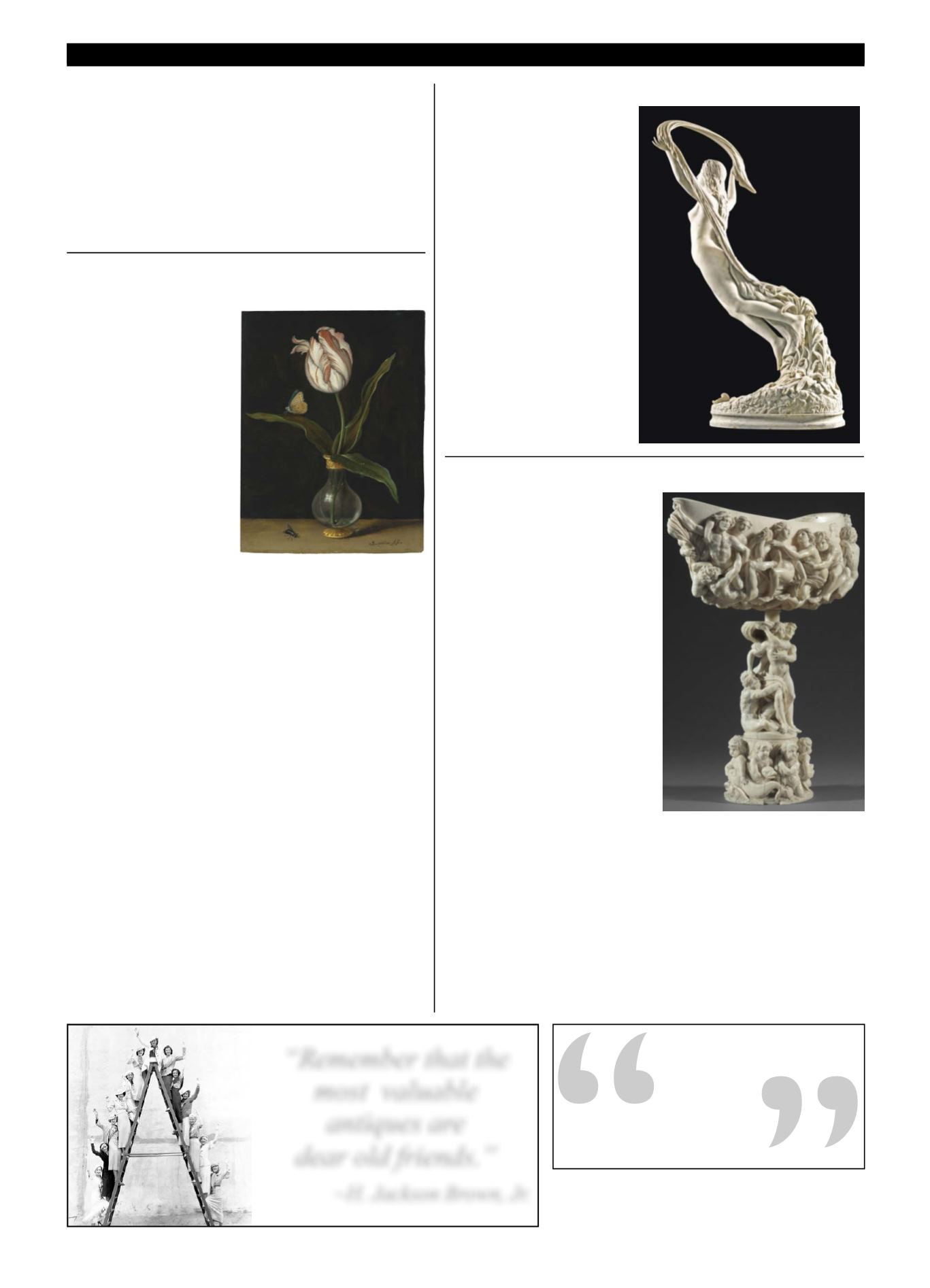

The “Rothschild Nef,” a 17th-century piece

that that has become closely associated with

Sotheby’s over the last 40 years, sold for

$438,830.

K

nown as the “Rothschild Nef” after

one of its 20th-century owners, Baron

Guy Édouard Alphonse Paul de Rothschild

(1908-2007), the 17th-century ivory model

seen here was first sold by Sotheby’s in

1975, in one of their Monaco sales.

It reappeared in their London rooms in

1996, when it emerged that it had been

acquired by the British Rail Pension Fund

(whose advisors were Sotheby’s) during the

years 1974 to 1980 in which that experimen-

tal art investment project operated.

At the 1996 sale it was bought by Alfred

Taubman, who was of course the owner

of Sotheby’s from 1983 to 2005. Then on

December 6 last year it voyaged once more

back to the New Bond Street salerooms and

this time sold for $438,830.

Taking their name from a type of medi-

eval sailing vessel, nefs are probably more

familiar as silver table ornaments, often with

wheels—but this one is rather different in

form.

A 15" tall model, it is attributed on the

grounds of its “virtuoso technique…ambi-

tious scale and complexity” to one of the

most talented ivory carvers of the age, Georg

Pfründt (c. 1603-1663). A South German

craftsman, Pfründt was also known as a mod-

eller in wax, a medallist, and an engraver.

Employing what was at the time an expen-

sive and exotic material and the services of a

master craftsman, this nef must have been a

major commission.

The vessel’s sides are carved with men and

idealised young women, perhaps river gods

and nymphs, who are entwined by billowing,

wave-like drapes. The stem is formed of a

trio of figures representing the rape of one

of the Sabine women, a composition broadly

inspired by Giambologna’s monumental

marble of the same subject in the Loggia

dei Lanzi in Florence. The foot of the nef

is encircled by frolicking infant tritons and

putti playing with dolphins.

An ivory masterwork, it may have been

intended for display in a princely or noble

kunstkammer

or

wunderkammer

. Such cabi-

nets or rooms had long been devoted to natu-

ral and artificial wonders, from fine bronzes

and paintings to uncarved gems and animal

specimens, but the 17th century saw a vogue

for adding superbly worked pieces in amber,

rhinoceros horn, and, in particular, objects

modelled from elephant or marine ivory.

Letter from London continues on page 6-D

“Remember that the

most valuable

antiques are

dear old friends.”

~H. Jackson Brown, Jr.

Nothing is really work unless

you would rather be doing

something else.

J.M. Barrie