6-D Maine Antique Digest, April 2017

-

FEATURE

-

-

6-D

A Snowy Start to the New London Season

S

ki poster sales at Christie’s South

Kensington have traditionally been

one of the earlier, if rather isolated,

events of the new year auction calen-

dar in London, where sales—or at least

those held by Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and

Bonhams—tend to kick off rather later

in the year than is the case in New York

City. (Three lots from another early sea-

son event held by Sotheby’s, a January

19 sale called “Of Royal and Noble

Descent,” feature elsewhere in this

month’s selection.)

These early season poster sales at the

South Kensington saleroom do add a

welcome dash of colour to winter and

five litho posters from that lonely event,

held this year on January 11, are fea-

tured here.

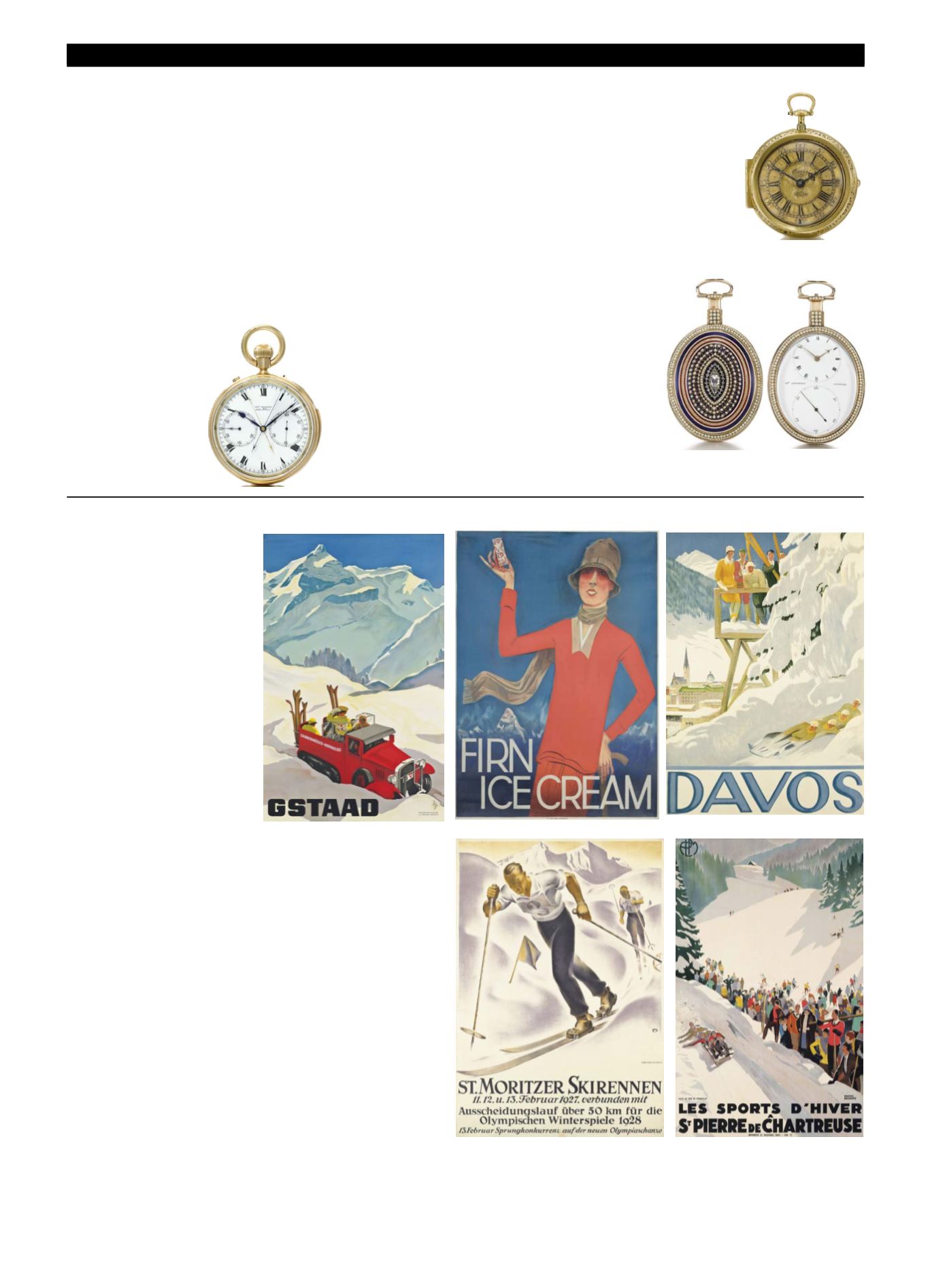

Alex Walter Diggelmann, born in

Switzerland in 1902, was not just one of

his country’s more celebrated graphic

designers, he was an adept orienteer, a

balloonist, and a toxophilite—though

as a fellow countryman of William Tell,

you will not be surprised to learn that

he favoured the crossbow rather that the

longbow.

Sold for $33,410, Diggelmann’s

Gstaad poster (A), a condition-A-

example, dates from 1934 but when the

Winter Olympics resumed in St. Moritz

after World War II, he was made offi-

cial designer for the 1948 winter games,

creating the event poster and special

celebratory stamps.

Though it seems a little curious now-

adays, right up until 1952 Olympic

medals were also awarded for paintings,

sculpture, architecture, literature, and

music inspired by sport. In 1936 and

1948 Diggelmann’s artwork brought

him a total of three Olympic medals—

one gold, one silver, and one bronze.

Otto Baumberger, born in 1889, had

been one of the earlier Swiss artists

to work as a full-time poster designer,

creating more than 200 designs, and is

sometimes referred to as the “spiritual

father” of the Swiss poster. He pro-

duced some of the earlier examples of

tourism-focussed posters in the coun-

try, though the example seen here is

promoting a different sort of cold expe-

rience—the delights of Firn ice cream

(B), which was apparently a favourite

among the fashionable set of the 1920s.

A: Alex Diggelmann

B: Otto Baumberger

C: Emil Cardineaux

D: Carl Moos

E: Roger Broders

Graded as condition B+, the poster sold

for $3040.

Although he initially studied law

at university in his native Bern, Emil

Cardinaux left for Munich in 1898 to

pursue his artistic training and there

studied under the German Symbolist

painter Franz Stuck, whose other pupils

included Klee and Kandinsky. Cardi-

naux further broadened his artistic stud-

ies in Italy and France but he returned

regularly to his homeland and built a

studio overlooking the Bernese Alps.

Cardinaux’s poster designs, say

Christie’s, are notable for their style

and simplicity, though the Davos poster

of 1918 featured here (C) seems rather

more traditional. Graded condition B-,

it sold at $25,820.

Born in Munich in 1878, Carl Moos

moved to Zurich in 1916, creating strik-

ing posters advertising resorts ranging

from Davos to St. Moritz. In 1928, the

year in which the

St. Moritz Skirennen

poster seen here (D)—now considered

a classic Moos design—was produced,

his work promoting the country’s Win-

ter Olympics won him a silver medal.

This condition-B+/A- example was

sold at $22,780.

A Parisian, Roger Broders (1883-

1953) became one of the most prolific

poster designers of the 1930s, best known

for sun-soaked advertisements for French

resorts as well as others aimed at luring

the viewer farther afield to Italy and North

Africa—but his depictions of Swiss ski

resorts are no less celebrated. Dating to

1930,

Les Sports d’Hiver à St. Pierre de

Chartreuse

(E), graded B/B+, was sold for

$12,150.

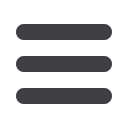

The Charles Frodsham watch

of 1902, inscribed as a gift from

J.P. Morgan to William Gould

Harding, sold for $370,945.

Two views of the oval William

Anthony watch of circa 1800

that sold for $265,630.

Celebrating the English Watch—Time for Three More Cheers

T

homas Tompion’s watchmaking skills fea-

ture among the three timepieces I have

selected from the third sale that Sotheby’s

have now mounted to disperse a distinguished

collection of English watches. This is just as

well, really, as this part of that “Celebration of

the English Watch…” series of auctions, held

on December 15 last year, was subtitled “The

Genius of Thomas Tompion.”

Dating from the years 1708/09 and num-

bered 307, the gold, pair-cased, quarter repeat-

ing verge watch seen in the illustration at right

was sold for $234,380.

It was not, however, the most expensive

watch of the day. That honour went to the large

gold, open-face, minute repeating, split sec-

onds, keyless chronograph watch seen below.

A watch by Charles Frodsham of

London that dates from 1902, it is

one linked with the maker’s most

famous clients, the Morgan banking

family of New York. That associa-

tion began when Junius Morgan

became a business partner in the

English branch of the bank-

ing house George Peabody &

Co. in 1854, but the purchase and maintenance

of fine clocks and watches was continued and

taken to a new level by John Pierpont Morgan

(1837-1913).

In 1883 J.P.M. presented a complicated

watch to his personal valet, George William,

on the occasion of William’s marriage and that

watch was the forerunner of the series of fine

Frodsham watches ordered for presentation to

close friends or partners by the Morgans—a

tradition that continues to this day.

Made between 1897 and 1931, some 25 of

those Frodsham watches—state-of-the-art,

open-face tourbillons with minute repeating,

split second chronograph, minute register and

constant seconds—are known, either as extant

examples or from archive records. And ten of

them have made auction appearances.

They were at the time of manufacture one of

the most complicated and expensive English

production watches available, retailing at what

in the early decades of the last century would

have been the equivalent of around $800 to

$1200.In 2016 this latest example to come

to auction sold at $370,945.

The third watch in my selection is an

eight-day gold, enamel and split-pearl-

and diamond-set duplex watch that was

made around 1800 by William Anthony

of London.

Specialising in watches for the Chinese mar-

ket, Anthony is famous for such elaborately

decorated oval watches, the rarest of which

feature expanding hands that are articulated to

follow the oval line of the dial.

“The sumptuous yet tightly ordered deco-

ration to the case of the present watch,” say

Sotheby’s, “is complemented by the wonder-

ful clarity of the white enamel dial which is

divided into two equal sections, with hours and

minutes above subsidiary seconds.”

Continued from page 3-D

In that same Antiquorum of

Geneva sale was a further Wil-

liam Anthony watch that had

similar design elements to the

present watch, but that one was

numbered 1935, and the more

recent Sotheby’s example is

numbered 1931.

This watch is part of a small group of fewer

than ten similar watches by Anthony,

which seem originally to have been

made in pairs. In 2001 one matched

pair, numbered 1913 and 1914, was

sold (though as separate lots) as part

of the Sandberg collection.

On its own, the Sotheby’s watch

sold at $265,630.

The early 18th-century

Tompion watch sold for

$234,380.