12-B Maine Antique Digest, May 2015

- auction -

J

ames D. Julia kicked off its 2015

auction year with a three-day selling

binge of over 2000 lots and a grand

total of more than $3.5 million on Feb-

ruary 4-6 in Fairfield, Maine. According

to the post-sale press release, over 5000

Internet bidders representing 61 countries

competed with the phones, absentee bid-

ders, and attendees at the sale.

The auction was rife with items of

esoteric historical significance. One lot

focused on Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins

(1849-1908), who was born into slavery

at a time before autism was recognized

and is now understood to have been an

autistic savant. During the 19th century,

he was one of the best-known American

performing pianists. Blind from birth,

Wiggins was sold at an auction in 1850,

along with his parents, to James Bethune,

a Georgia lawyer, as a “throw-in.” At age

four, Tom started to display an intuitive

piano ability after listening to Bethune’s

daughters play, and by age five he had

reportedly composed his first tune. Wig-

gins frequently turned natural sounds,

such as the beating of rain on a tin roof

or the crowing of a rooster, into musical

compositions.

By age eight, Wiggins was recognized

as a musical prodigy and was touring

extensively throughout the South. Over

his lifetime he earned his promoters the

equivalent of around $5 million in today’s

money. He could accurately mimic a con-

versation of up to ten minutes in length

but could communicate on his own only

with minimal words, grunts, and gestures.

Of one of his performances, an unsigned

1894 review in the

Nebraska State Jour-

nal

that has been attributed to author Willa

Cather stated, “It was a strange sight to

see him walk out on the stage and with

his own lips—and another man’s words—

introduce himself and talk quietly about

his own idiocy.... There was an insanity,

a grotesque horribleness about it that was

interestingly unpleasant.... One laughs at

the man’s queer actions, and yet, after all,

the sight is not laughable. It brings us too

near to the things that we sane people do

not like to think of.”

Atrove of over 50 pieces of sheet music,

broadsides, and photographs related

to Blind Tom had come from a private

local history museum formerly run by

George Greene (d. 2014) in Phenix City,

Alabama. The lot included newspapers

advertising Tom’s concerts, broadsides,

sheet music, photographs, cartes de vis-

ite, and more. It also contained a phren-

ological journal with a full page dedi-

cated to Blind Tom. According to the cat-

alog, the whole collection took an entire

room to display at Greene’s museum.

The collection sold for $29,625 (includ-

ing buyer’s premium), easily besting the

$10,000/20,000 estimate.

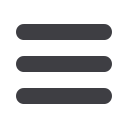

A medal commemorating the ill-fated

Jeannette

expedition to the Arctic in

1879-82 caused a small stir. The

Jean-

nette

was privately owned but sailed

under naval orders with a crew of 33 men.

Under the command of Lieutenant George

W. DeLong (1844-1881), the expedition

is credited with discovering three of the

uninhabited islands in the East Siberian

Sea now known as the DeLong Islands:

Jeannette, Henrietta, and Bennett Islands.

The

Jeanette

became trapped in an ice

pack in the Chukchi Sea in September

1879. It eventually was crushed by ice and

sank in 1881. DeLong and his crew then

attempted to traverse the ice pack to Sibe-

ria, pulling their supplies and three small

boats. One boat team was lost and never

found. DeLong’s company reached land,

but only the two strongest men were then

sent ahead for aid. Those were the only

two of DeLong’s boat to survive. The cap-

tain himself perished of starvation, and

the third boat was eventually rescued.

Herbert W. Leach, born in 1858 in

North Penobscot, Maine, was among the

survivors on the rescued boat. Only 13 of

the original company of 33 survived the

expedition. Leach was awarded a Con-

gressional silver medal with the inscrip-

tions “Jeannette Arctic Expedition 1879-

1882,” “In Commemoration of Perils

Encountered and as an Expression of the

High Esteem in which Congress Holds

His Services,” and “Act Approved Sept.

30. 1890.” According to Julia’s catalog,

eight gold and 25 silver medals were

struck by the Philadelphia Mint and were

awarded to the survivors or families of

the deceased. The medal at Julia’s auction

descended in the family of Herbert Leach

and had changed hands at least once

before arriving at the auction. It has now

been returned to a Leach family member.

The buyer at $21,330 was Mainer Fer-

nald Leach, a great-nephew of Herbert

Leach. He may not be keeping the medal

to himself for long. Several museums,

including the Maine State Museum and

the Wilson Museum in Castine, Maine,

have expressed an interest in displaying

it. “[Herbert] Leach lost his big toe and

some of the others. He was the last to die

of the whole group.... He died in 1935,”

Fernald Leach told me later, adding that

the medal “will probably wind up in one

of the museums. I couldn’t sell it.”

As we’ve often seen before, Asian

antiques came on strong, with more than

a handful of lots wildly surpassing their

estimates. A Chinese Republic period

celadon jade scepter hit five figures at

$24,700. A 19th- or early 20th-century

Tibetan thangka of the Buddha was nailed

down at $13,585. And the $189,600 that

was paid for a bronze Ming Dynasty

sculpture of Guanyin exceeded every-

thing else in the auction.

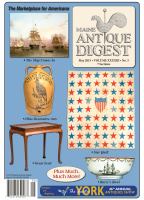

Where else could a solid piece of cast

iron bring five grand? Here’s the back

story. On August 5, 1864, Admiral David

Farragut (1801-1870) was in command of

the flagship U.S.S.

Hartford

at the Battle

of Mobile Bay in Alabama. Lashed to the

rigging, he hollered through a trumpet to

the nearby U.S.S.

Brooklyn

, “What’s the

trouble?” The shouted answer came back

“Torpedoes,” to which Farragut report-

edly replied, “Damn the torpedoes! Four

bells, Captain Drayton. Go ahead, Jouett,

full speed. ” His words have been popu-

larly reinterpreted as “Damn the torpe-

does! Full speed ahead!”

According to Norman Flayderman,

who cataloged the cannonball for one

of its previous sales, the 8" cannonball

offered by Julia was fired from the Con-

federate Fort Morgan on shore, came

whistling by, and landed on the deck of

the

Hartford

, doing virtually no damage.

The missile was donated to a New York

historical society, where it remained for

132 years until 1996. There had been a

couple of ownership changes since then.

It brought $5332.50.

For more information visit (www.

jamesdjulia.com) or call (207) 453-7125.

James D. Julia, Inc. Fairfield, Maine

Julia Opens for $3.5 Million

by Mark Sisco

Photos courtesy James D. Julia, Inc.

Where else could

a solid piece of

cast iron bring five

grand?

The 8" cannonball that missed killing

Admiral David Farragut aboard the U.S.S.

Hartford

at the Battle of Mobile Bay when it

fell intact onto the deck of the ship brought

$5332.50.

Congressional silver medal

commemorating the

Jean-

nette

Arctic expedition, 1879-

82, given to team member

Herbert Leach, $21,330.

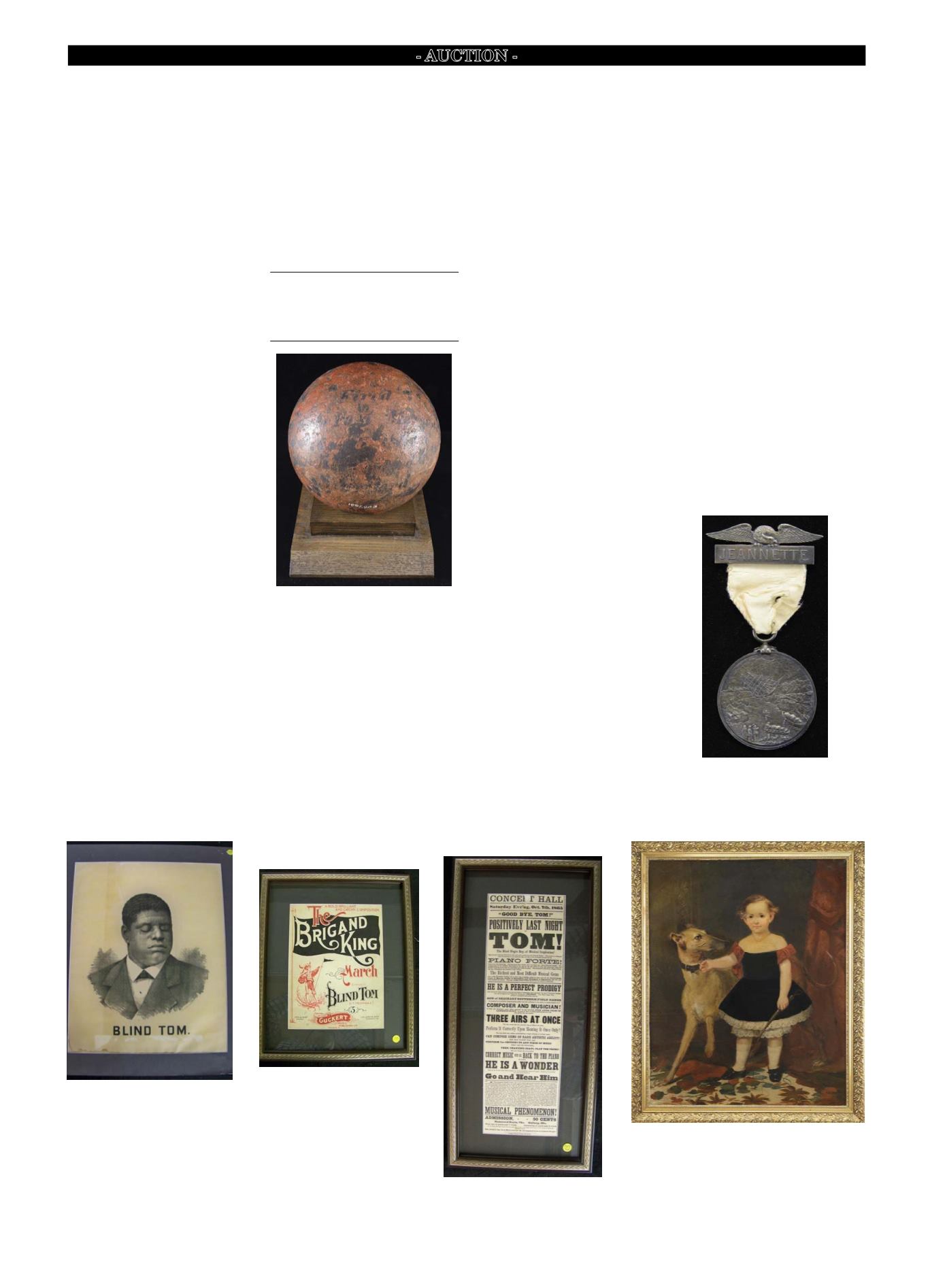

A collection of about 50 paper items relating to “Blind Tom” Wiggins, an autistic

savant born into slavery who showed evidence of prodigious musical talent by

age four, sold for $29,625. Wiggins died from a major stroke in 1908, having

earned fortunes for his owners and promoters but precious little for himself.

It was “strike three” for this attractive 50" x 40" (sight

size) oil on canvas portrait of a young boy in a black

dress by NewYork artist James Henry Cafferty (1819-

1869), showing the lad with his dog on a floral carpet

with a russet drape in the background. It had come up

for auction twice before, and this time nobody went

for it with a reduced estimate of $8000/12,000.