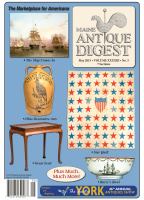

12-A Maine Antique Digest, May 2015

A

fter the 2015 Philadelphia Antiques Show

was canceled, Anne Hamilton and Nancy

Kneeland from the volunteers and Richard

Worley and Joan Johnson, the current and

past chairs of the Antiques Show Advisory

Committee, met to focus on the possibility of

a 2016 show.

Catherine Sweeney Singer and the commit-

tee of four mutually agreed that the 2016 show

needed a fresh start. Diana Bittel and Ralph and

Karen DiSaia have been engaged to do a feasi-

bility study to evaluate location, date, size, and

focus. The committee gave them six weeks to

come up with a business plan to present to Penn

Medicine.

Bittel thinks a 2016 show is possible. “We

have several spaces we like, and we have deal-

ers on board,” she said. “We are rebuilding re-

lationships with the committees so important

to the show’s success and looking at all the fi-

nancial considerations,” said DiSaia. “We are

building on the history of the show; we like an

April date and looking for new ways to make

it work.”

Bittel and DiSaia said they will meet with the

volunteers and with Penn Medicine in mid-April

and will announce the date and place as soon as

it is approved.

Philadelphia Show

to Be Revived

O

n March 22, the Minnesota Marine

Art Museum inWinona, Minnesota,

unveiled the 40½" x 68" version of

Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 masterpiece

Washington Crossing the Delaware

,

perhaps the most famous and iconic

American painting.

It was acquired by Mary Burrichter

and Robert A. “Bob” Kierlin, the mar-

ried couple who played an important

role in founding the museum and are

now “collecting partners.” (Kierlin

helped launch Fastenal, aWinona-based

industrial supply company.) The sale

was arranged by Burrichter and dealer

Dr. John Driscoll of Driscoll Babcock

Galleries in New York City; the cost

was not revealed.

According to the museum, Leutze

painted three versions of his famous im-

age. The earliest version was destroyed in Germany during

the Second World War. A near replica, though much larg-

er at 149" x 255", is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

in New York City. The Minnesota Marine Art Museum’s

version had been owned privately for the past 164 years.

For most of the past 40 years, it has been on loan and dis-

played in the reception area of the West Wing of the White

House in Washington, D.C. The painting had been previ-

ously exhibited at the New York Crystal Palace in 1853, the

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1854, and at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1895.

Washington Crossing the Delaware

joins a collection of

Hudson River school paintings, along with works by Thom-

as Cole, Asher B. Durand, John Frederick Kensett, Frederic

Church, Jasper Cropsey, and Martin Johnson Heade.

Washington Crossing the Delaware

Goes from White House to Winona,

Minnesota

Photo courtesy Minnesota Marine Art Museum.

by Lita Solis-Cohen

Winterthur recently announced two im-

portant acquisitions.

John Shearer Chest Made for Salome

Kramer

At the Furniture Forum (March 4-7)

Winterthur announced the purchase of a

chest of drawers made by John Shearer

(worked 1790-1820) for Salome Kramer

of Frederick County, Maryland, in 1809.

Shearer signed the walnut, oak, and pop-

lar chest eight times, dated it, and wrote

for whom it was made. The purchase of

this chest of drawers advances Winter-

thur’s goal of continuing to broaden the

geographic scope of its collection through

acquisition of objects made and used in

the American South. The chest was ac-

quired from Sumpter Priddy III of Alex-

andria, Virginia, the dealer who brought

it to the Delaware Antiques Show in No-

vember 2014.

In her 2011 book,

The Furniture of John

Shearer, 1790-1820: “A True North Brit-

ain” in the Southern Backcountry

, Eliz-

abeth A. Davison reported that between

circa 1790 and circa 1808 Shearer was a

householder on tax lists, first in Berkeley

County, Virginia, then, more specifical-

ly, in Martinsburg. In 1800, he moved to

Frederick County, Maryland, and in 1810

returned to Virginia’s Piedmont where he

made furniture and constructed houses

in Loudon County before disappearing

altogether from the records in 1818. For

evidence of his cabinetmaking practices,

Loyalist political views, business deal-

ings, and geographical movements, she

turned to his furniture, including Salome

Kramer’s chest.

Davison writes that this chest express-

es Shearer’s distinctive “North Britain”

(lowland Scottish) political aesthetic

and identifies it as one of only three case

pieces that Shearer decorated with a drop

pendant at the center of the skirt, shaped

to echo the inlaid swag at the center of

the top drawer. Shearer adorned the front

with inlay inscribed with details that Da-

vison has called “a memorial to those who

fought in the battles of Trafalgar and Wa-

gram, and in a series of naval skirmishes

in the Mediterranean and West Indies”

and “one of the most exuberant of all of

Shearer’s loyalist expressions.” These in-

clude “Victory to the Great Duke Charles

of Austria” inscribed in the center lozenge

of the top drawer, “The Immortal Lion

A

d

L

d

Nelson” inscribed in the crowned

banner above the lozenge, and “Ad Coch-

ron” inscribed in the pendant below the

lozenge, all of which reflected news from

the local papers. Davison explains that

the Great Duke Charles of Austria fought

Napoleon at the battle of Wagram near Vi-

enna, July 5 and 6, 1809. Admiral Nelson

defeated Napoleon’s combined French

and Spanish fleet at the battle of Trafal-

gar, and “Ad Cochron” refers to Admiral

Alexander Cochrane, who defeated the

Franco-Spanish fleet at Santo Domingo

in 1806.

Above the masks from which the cen-

ter pendants hang are inscribed the names

“Colenwood” (proper right) and “North-

esk” (proper left). “Colenwood” refers to

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, the

second in command at the battle of Trafal-

gar; “Northesk” refers to Lord Northesk,

the titled Admiral William Carnegie, the

third in command at Trafalgar. Shearer

inscribed a boss inlaid at the center of the

top’s front edge “To Miss Salome Kram-

mer” [sic] and a banner suspended from

swags on the second drawer “By Shear-

er.” Inscriptions on the lozenge inlays,

drawn with fouled anchors, above the

drawer pulls on the top drawer read “Glo-

ry and Death”

(

proper

left

)

and

“Death

and Glory” (proper right).

In addition to the inscribed inlays,

Shearer marked the interior of the case

eight times. On the top drawer he wrote

his name “Shearer” on the left and again

on the interior back, adding the date 1809.

On the exterior back of the top drawer he

wrote “Shearer Joiner 1809” and on the

exterior proper right “Shearer” again. On

the second drawer on the inside back, he

wrote his name and date 1809 again, and

on the back of the second drawer “Shear-

er a joiner from Edinburgh.” On the third

drawer bottom, he wrote “By Shearer to

Miss Sarah Cramer [sic] 1809” and on

the interior of the case behind the third

drawer “Made to Miss Salome Kramer &

payed for by me John Shearer Sept 1809.”

Davison surmises that Shearer had made

Salome’s chest not as a present but, along

with a similar chest for Salome’s sister

Christina, as part of a barter agreement

with their father, Johann Adam Kramer.

With his brother, Baltzer Kramer

(1749-1813), a famous glassblower, Jo-

hann Adam Kramer (1755-1828) em-

igrated from Germany to work in the

Stiegel glass manufactory in Manheim,

Pennsylvania. When the factory closed,

both brothers moved their families to

Frederick County, Maryland, where they

worked for John Frederick Amelung.

Aside from replaced brasses, minor

patches to the ogee feet, and a reworked

finish, this chest of drawers had suffered

few alterations. Announcing its acqui-

sition at the Furniture Forum, curator

Joshua W. Lane called it a particularly

noteworthy addition to the Winterthur

collection.

In honor of Wendy Cooper, who retired

in June 2013 after serving as Winterthur’s

curator of American furniture since 1995,

Winterthur has acquired a dressing bureau

with a stenciled label in its top drawer.

The label was used by Isaac Vose & Son

in Boston from 1820 through 1825. The

dressing bureau was acquired through

furniture scholar and broker Clark Pearce,

who identified the piece in a private col-

lection and facilitated its private sale.

Pearce, who with Robert D. Mussey Jr.

has done research on the Seymour shop

in Boston, found that in 1817, Thomas

Seymour closed his shop and wareroom

and became shop foreman—first for Bos-

ton cabinetmaker James Barker, then, in

1819, for Isaac Vose, Joshua Coates, and

Vose’s son, Isaac Vose Jr., whom Vose Sr.

and Coates had recently brought into part-

nership under the name “Vose, Coates, &

Co.” After Coates’s death in 1819, the

firm continued as “Isaac Vose & Son.”

Isaac Vose Sr. died in 1823, and Seymour

continued as shop foreman for Isaac Vose

Jr., overseeing production of Regency and

Grecian-style furniture until Vose closed

the shop and sold the furniture, lumber,

tools, and other effects at auction in 1825.

Pearce wrote in his report to Winter-

thur: “The craftsmanship of this dressing

bureau is superb, underscoring Thomas

Seymour’s hands-on role in the shop. In

fact, the drawer blades above the low-

er three drawers have script pencil in-

scriptions ‘N2,’ ‘N3,’ and ‘N4,’ all in

Seymour’s distinctive hand. Seymour’s

artistic ability to create thoughtful com-

positions in wood grain is evident in

his use of branch veneers on the drawer

fronts, cut from the same bolt, alternating

direction on each drawer. The projecting

‘frieze’ (upper) drawer is veneered with

horizontally bookmatched branch veneers

to contain the drama of the three drawers

below, and re-direct the eye to the archi-

tectural structure of the chest of drawers.”

The dressing bureau retains all its origi-

nal hardware, fire-gilt mounts, and mirror

glass. The drawer knobs, stamped “Bar-

ron’s Patent,” were made by the Birming-

ham, England hardware manufacturer

Barron’s, following a design patented in

1818, according to Pearce. These knobs

have been observed only on pieces that

are labeled, documented, or attributed to

Isaac Vose & Son, suggesting that Sey-

mour and Vose had an exclusive impor-

tation relationship with the Barron’s firm

in England.

The Vose dressing bureau completes

the story of the top furniture shops in the

second decade of the 19th century for

Winterthur, which has furniture from the

same period made in Philadelphia and

New York. Furniture by Isaac Vose (and

Thomas Seymour in the second phase of

his career) may not be as well known as

that by Duncan Phyfe, Charles-Honoré

Lannuier, and Joseph Barry, but it is every

bit as notable. This dressing bureau com-

plements the dressing bureau by Philadel-

phia cabinetmaker Walter Pennery made

in the same period in Winterthur’s collec-

tion.

Winterthur Announces Acquisitions

Vose Dressing Bureau