26-D Maine Antique Digest, May 2015

- AUCTION -

S

he had nice legs and feet, wore a fancy

skirt, and showed some age despite a

nip here and a tuck there but still had

nice proportions. A southerner by birth but

a northeasterner most of her life, she led a

privileged life in fancy homes, and many a

cup of tea she held. Most of her contemporar-

ies were long gone, but she was a survivor, a

product of the time when the Williamsburg,

Virginia, area was the center of American

Colonial life.

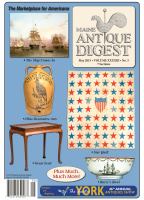

The 18th-century Queen Anne tray-top

tea table with an old refinish was up for sale

at the February 20 and 21 Cottone auction

in Geneseo, New York, south of Rochester.

It was lot 657, out of 738, and pictured not

on the front or back of the 73-page catalog

but as one of nine pictures on page 65, and

it was estimated at only

$1500/2500. Described in

the catalog as “NE Queen

Anne tray top tea table,

18th century, mahogany,

scalloped skirt, pad feet,

old refinish. Ht 27" W 30

1/2"; D 19", ex Walter Vogel collection,” it

looked fetching, but not to the extent that the

ensuing bidding showed.

Cottone opened at $10,000, so that was an

indication something was afoot. Two bidders

went wild, one on the phone and one repre-

sented by an agent on the floor, with the floor

bidder winning it at $299,000 (includes buy-

er’s premium).

How? Why? As the clapping continued,

that’s what everyone was asking, and the

answer popped into Buffalo, New York,

dealer Dana Tillou’s mind as the piece sold.

Tillou had taken a casual look at it—nice, he

said, but nothing out of the ordinary, not a

drop-dead piece. He admitted that he knows

and deals in New England pieces and that is

his expertise. So the piece seemed to be of

slight interest to him as it looked like a typi-

cal New England tea table. He watched from

the back of the auction gallery, straining to

see who in the crowd was bidding.

Then the “aha” moment—she had to be

southern! Southern, Tillou told

M.A.D.

after

the sale. Why else the high price?

Another area dealer said he learned shortly

before the sale that the piece was important

and rare and from Virginia, and a lot of peo-

ple were interested in it. There had been a

high level of interest, in fact, evident to Cot-

tone from the inquiries he began getting as

the word spread.

According to scholars and museum staff

who specialize in southern furniture, the table

is very important, as it is no ordinary New

England piece but a rare southern master-

piece by the first documented cabinetmaker

from Colonial Virginia.

Thanks to research by Ronald Hurst of

Colonial Williamsburg (which has a similar

tea table) and Robert Leath of Old Salem

Museums and Gardens in Winston-Sa-

lem, North Carolina, and the publication

of

Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern

Virginia

,

1710-1790

, we know this was a

piece by cabinetmaker Peter Scott, who

came from England to Williamsburg in

1722 and continued his trade until 1775. He

died at age 81, which was remarkable lon-

gevity given the times. He was often called

the “dean of Williamsburg cabinetmakers,”

and it is said that Thomas Jefferson bought

tea tables from him. Also Scott is said to

have been a tenant of George Washington,

and he seems to have paid his rental bills

by taking commissions

for fine furniture for

the Washington family.

Pieces that definitely

can be attributed to Scott

are very few—the one at

Colonial Williamsburg

and two others in private hands, according

to scholars. And only recent research (2006)

has changed the printed information of the

1970s and 1980s about which Virginia cabi-

netmaker made what pieces.

But who knew about

this

piece? Well,

according to Sumpter Priddy III, longtime

dealer in Alexandria, Virginia, all of those

who collect early Virginia pieces did, includ-

ing institutions and collectors, and because

he “knew who was chasing it,” Priddy said

he did not bid. “Hard for anything like that

to slip through. No secret in the southern

circles,” he said.

“It was no surprise that the

piece turned up outside of the South. A huge

percentage of the South’s early furniture

migrated out of the region—much of it in the

late eighteenth and early nineteenth century

when southern families migrated westward

for better land, but also a surprising number

of pieces in the late nineteenth and twentieth

century, before regional scholarship made it

possible to identify the material products of

our fractured culture.”

The consignor was the daughter of old-

time collector/dealer Walter Vogel of Roch-

ester, New York, who bought from old-time

dealers like Sack. Most of Vogel’s collection

was sold in New York City after his death

decades ago, but a few pieces stayed with his

daughter. “She lived with the pieces,” said

Sam Cottone. She had consigned about 30 of

them to this sale, including a rare inlaid min-

iature chest that made $4830; a Hepplewhite

bowfront chest that got $1380; and three

New England Windsor chairs, $1092. (As

recently as 2011, Christie’s sold an ex-Vogel

piece for $194,500, a Federal inlaid

Pembroke table, with the prove-

nance of Eddy Nicholson, among

others.)

So after the clapping ended and

the crowd calmed down, it was evi-

dent that serious collectors/dealers

of early Virginia furniture knew

about the table and had been hold-

ing their cards close. Cottone would

not reveal the two final bidders, say-

ing they were private collectors.

Exciting story, right? But Cottone

had other items to shout about, as

he usually does. The other six-fig-

ure piece was about as opposite as

it could be from the southern lady.

Its consignor, a longtime collector

in Rochester, has distinctly opposite

taste. Richard Brush, former owner

of SentrySafe, likes modern, and

among the dozens of pieces he sent

to Cottone was an 8'9" kinetic sculp-

ture of stainless steel. By George

Warren Rickey (1907-2002), the

signed piece brought $115,000. It

was featured on the inside cover of

the catalog, in a full page at that!

Cottone Auctions, Geneseo, New York

An Important Discovery at Cottone

by Fran Kramer

Photos courtesy Cottone Auctions

Then the “aha”

moment—she had

to be southern!

In the Cottone sale catalog, this tea

table was described as a New England

Queen Anne tray-top tea table and

was estimated at $1000/2500. It was

not a New England table, and it sold

for almost 300 times the low estimate.

“Remarkable. It’s a special addi-

tion to the literature on the subject.

A singular object and unequivocally

the work of Peter Scott of Williams-

burg,” said dealer, scholar, author,

and established expert on southern

furniture Sumpter Priddy III of Alex-

andria, Virginia. Contacted after the

sale, Priddy gave a sincere, enthusias-

tic endorsement of the tea table, which

brought $299,000 from an unidenti-

fied man in his 40s or 50s, said to be an

agent bidding in person for a collector.

“First of all, I am not surprised that a

table of such rarity turned up where

it did, as many early southern pieces

are found in the Northeast as so much

early furniture was pulled out of the

South into major metropolitan areas

as our country evolved.”

Priddy has handled a lot of south-

ern furniture over the years, some by

Robert Walker, another early docu-

mented Virginia cabinetmaker, and a

piece or two by Scott, selling to both

institutions and collectors. Priddy also

wrote the introduction to

Furniture of

Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia,

1710-1790

in 1979 and edited the

manuscript.

Robert Leath, chief curator at Old

Salem Museums and Gardens in Win-

ston-Salem, North Carolina, wrote in

an e-mail, “Ron Hurst and I unraveled

the mystery of Peter Scott and Colo-

nial Virginia cabinetmaking almost

ten years ago. After figuring out

that the body of work that had been

attributed to Scott was actually made

by a different cabinetmaker working

in a completely different location, i.e.,

Robert Walker, we published our find-

ings in the 2006 issue of Chipstone’s

journal,

American Furniture

.

“Ron’s article was titled ‘Peter

Scott, Cabinetmaker ofWilliamsburg:

AReappraisal,’ and mine was ‘Robert

and William Walker and the ‘Ne Plus

Ultra’: Scottish Design and Colonial

Virginia Furniture, 1730-1775.’

“Ron and I realized that the highly

carved and ornamented furniture

group that had been attributed to

Peter Scott all had histories in the

Rappahannock River valley, far away

from the Colonial capital where Scott

worked. A few documents proved that

these items were actually made by the

Scottish émigré brothers Robert and

WilliamWalker, who came to Virginia

in the 1730s to build architecturally

ambitious houses and to furnish them

with stylish baroque furniture that

reflected the wealth and taste of north-

ern Virginia’s merchant-planter elite.

“Simultaneously, the cabinet shop

of Peter Scott, in Williamsburg, pro-

duced much of the ‘neat and plain’

cabinet furniture—tea tables, dining

tables, dressing bureaus, desks, and

desk-and-bookcases—that epitomized

the more reserved taste of the south-

ern Tidewater region. Scott’s sphere

of influence extended from Williams-

burg to the south side of the James

River and to the north side of the York

River and slightly beyond, but we dis-

covered that the Rappahannock River

was its own economic sphere with its

own cabinetmakers.

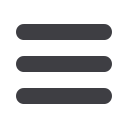

“The very elegant Chinese-inspired

tea table that sold at Cottone is one of

a small handful that we identified in

our research, including one in the col-

lection of Colonial Williamsburg. Its

record price reflects the importance of

Peter Scott as one of Colonial Virgin-

ia’s first urban-trained cabinetmak-

ers who worked in the Colonial capi-

tal for almost fifty years, and the very

high quality of his work. We don’t

know who owned it in the eighteenth

century, but it was certainly a mem-

ber of the Tidewater aristocracy.”

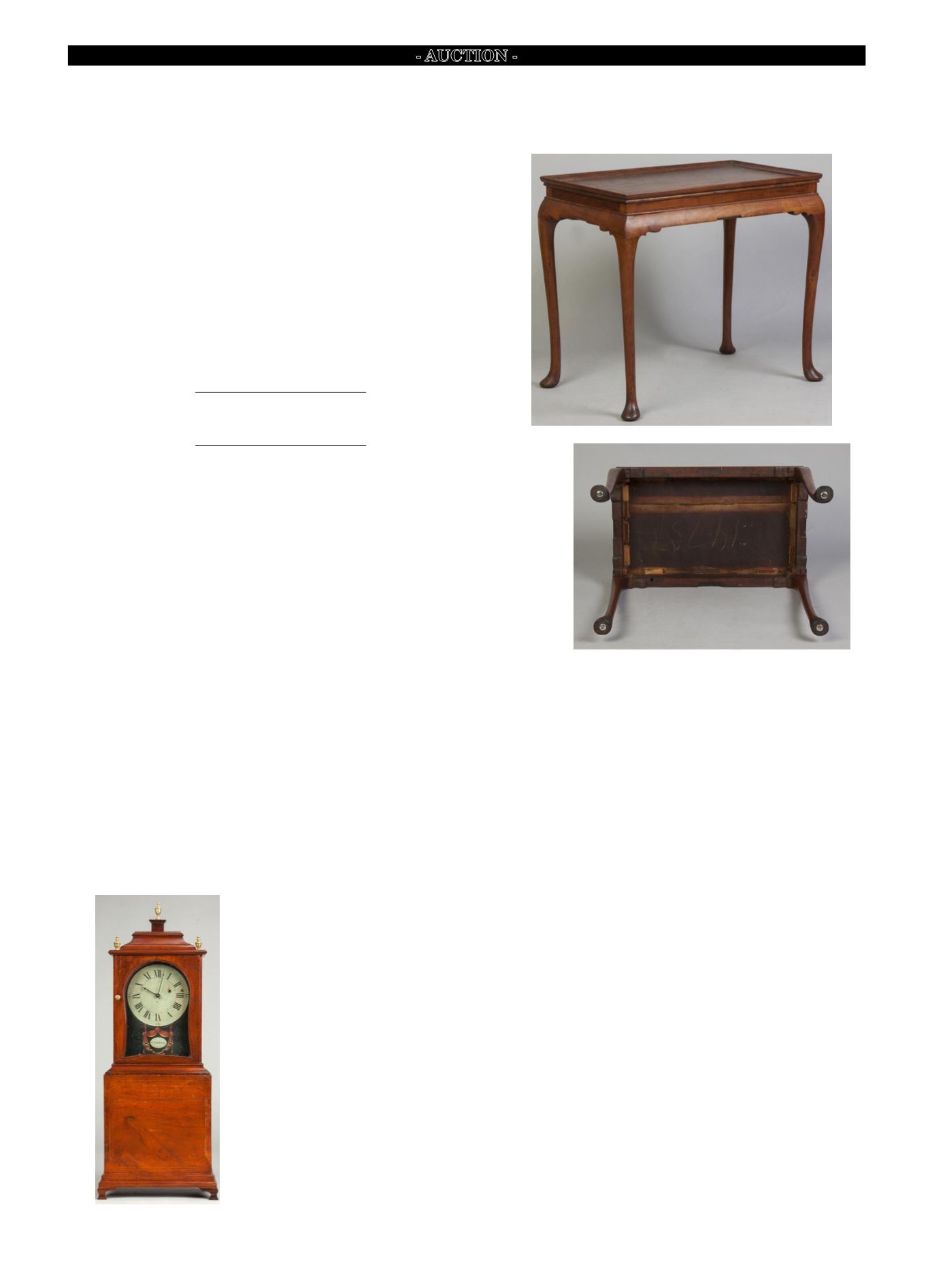

When is a clock

more than just a

timepiece? When

it’s a rare Stephen

Taber shelf clock

with old patina

and an original

signed iron dial. It

sold for $19,550 to

a phone bidder.