8-D Maine Antique Digest, May 2015

- FEATURE -

T

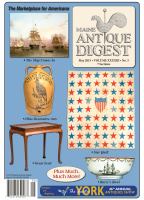

he splendid silver model of the German bat-

tleship

Kaiser Friedrich III

, seen upper right

and below in a close-up detail, was presented

over a hundred years ago by officers of the 1st

Squadron of the Imperial German Fleet to Vice

Admiral, Prince Heinrich of Prussia, whose flag-

ship it had been. Presumably this presentation was

made in 1903, on the occasion of his replacement

in that role by Admiral Hans von Koester.

The real thing had been launched on July 1, 1896,

by Kaiser Wilhelm II, the last German Emperor

and King of Prussia, who eight years earlier had

succeeded to power in what is known in German

history as the “Year of the Three Emperors.”

That was the year in which the Emperor Wilhelm

I died, but his only son, for whom the battleship

was later named, was already terminally ill and

reigned for only 99 days before he in turn was suc-

ceeded by his eldest son, Wilhelm II—or “Kaiser

Bill” as this haughty, impetuous eldest grandson of

Queen Victoria came to be contemptuously known

in England during the 1914-18 war that eventu-

ally brought about his abdication and exile to the

Netherlands.

Both Wilhelm II and his younger brother, Prince

Heinrich, a career naval officer who held vari-

ous commands and eventually rose to the rank of

Grand Admiral, had collections of elaborate mod-

els such as this. They were deemed very suitable

as prestigious gifts to members of the nobility and

those in high command.

Wilhelm II’s collection, as one might expect,

was rather grander and larger than that of his

younger brother, running to 15 comparable silver

models that were in 1919 transferred to the Hohen-

zollern Museum. Prince Heinrich’s model of the

Kaiser Friedrich III

, on the other hand, stayed in

his family until the mid-1950s, when it was sold at

auction in Bonn and acquired by the family of the

consignor to the February 24 Sotheby’s sale, “Of

Royal and Noble Descent,” that has contributed a

number of lots to this “Letter from London.”

The real warship saw service right up to the

opening years of World War I, but was involved in

few, if any, hostile engagements. She was decom-

missioned in 1915, used briefly as a prison ship,

then as a radio-telegraphy school before finally

being scrapped in 1920. The bow crest, bearing a

bust of Friedrich III, was however saved and can

still be seen in the Militärhistorisches Museum der

Bundeswehr in Dresden.

The finely detailed model, made by M. Fadder-

jahn of Berlin and a little over 4' long, was sold for

$115,835 in London.

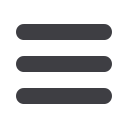

W

hen first I came across the illustration of

the gold collar reproduced here, in the cat-

alogue for a December 3, 2014, Sotheby’s

sale of European works of art, I thought immediately

of Anglo-Saxon ornament and jewellery—the use of

gold inset with garnets and highly stylised animal

heads forming part of the design—but this collar and

the associated beads are earlier still and from a land

far removed from Saxon England and the countries of

northern Europe.

This royal collar is not part of the world of Alfred

the Great or his antecedents, but much more closely

linked to that of Attila the Hun.

A lot with a Kyrgyzstan provenance that dates back

to the late 19th century, and perhaps made in that

region in the 5th century, this magnificent piece was

described and discussed in some detail and at length

in the sale catalogue by Dr. Noël Adams, a curator at

the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City

and a specialist in garnet cloisonné who is obviously

very familiar and knowledgeable on the Sutton Hoo

and other Anglo-Saxon finds.

In my distillation of just some of the highly infor-

mative background that she provided, I hope that I

have not been too brutal or unintentionally inaccurate.

And the headline is all my own and wholly unfounded

but appealing journalistic speculation.

The collar, it seems, can be related to a tradition

of high-status dragon and beast terminals that had

been introduced to the west by groups of nomadic,

horse-mounted warriors from the east, the Huns, who

had arrived in the region northeast of the Black Sea

in the late 4th century. Allying themselves with war-

riors from local tribes such as the Alans, they raided

the agricultural settlements and cities on the north-

ern shores of the Black Sea, eventually forcing large

numbers of Germanic-speaking peoples to flee to the

safety of the Roman Empire.

This was the beginning of a period when Hunnic

confederations, often made up of people from

different ethnic backgrounds, were major polit-

ical powers. Economic and cultural exchange

between east and west characterised the Hunnic

period and was enhanced during the period of

Attila’s control of the Carpathian Basin (c. 430-

455), when even the Byzantines paid gold tribute

to keep the confederation at bay.

Torcs, necklaces, and arm rings with beast-head

terminals have been found from Central Asia to

the Caucasus, Black Sea, and Carpathians, and

in the few cases where such finds have context,

it is clear that these ornaments were intended to

be worn by people of the highest social status—

hence its description as a royal piece.

Named for its first recorded 19th-century

owner, Sansyzbay Umutkor, the collar comprises

a woven gold strap with gold and garnet cloi-

sonné dragon terminals, the back ends of which

are open sockets fashioned to receive the strap

ends. Each dragon has a ribbed loop in its mouth

in order to tie the two ends together, and the two

beads that accompany the collar may have been

the weighted ends of the fastening ties, although

this cannot be proven.

The workmanship, says Dr. Adams, is typical

of many Hunnic-period ornaments where

craftsmen had access to garnet stones of

excellent quality, possibly sourced from

deposits in modern Afghanistan and

Pakistan. Their gold working techniques,

such as granulation, are superbly con-

trolled, but having few lapidary skills,

these same craftsmen relied on traded

stones, precut to certain shapes—such as

the rectangles seen on the terminals.

Despite the loss of some of the stones,

it remains a stunning work and sold in the

end for a mid-estimate $379,760.

A close-up view showing the

detailed workmanship.

A Battleship Fit for a Princely Grand Admiral

A detailed silver model of the German battleship

Kaiser Friedrich III

, sold for $115,835 by Sotheby’s.

A 5th Century Hunnic Dragon Collar—Worthy of Attila Himself?

The 5th-century Hunnic gold

collar with dragon head termi-

nals and (associated?) beads that

sold for $379,760 at Sotheby’s in

December—and at left, a close-up

of those dragon terminals.

Maine Antique Digest

2016 Antiques Trade Directory

All antiques dealers, group shop owners, auctioneers, and show promoters can be listed

in this volume, which will be bound separately and included with the January 2016

issue. Sign up before July 10, and you’ll pay only $45 for your listing ($60 after July 10).

Call us for a sign-up form or submit your listing online at

www.maineantiquedigest.com/directory.

(If you were in last year’s Trade Directory, you’ll receive a renewal notice.)

1-877-237-6623

Sign up now!

To reserve

your color ad

space in

M.A.D.’s 2016

Antiques Trade Directory

Call before

August 14, 2015.