Maine Antique Digest, May 2015 13-D

- FEATURE -

☞

S

andy Doig of Somers, Con-

necticut, sells the stuff that

everybody says nobody wants,

namely, brown furniture, in par-

ticular, lower- to mid-level formal

pieces and shellac-finished “high

country” items. He has been deal-

ing in this material for 30 years

and says he sees some stirrings in

the marketplace. He feels the era

of total collapse—that is, the era

of $300 slant-front desks and $100

Sheraton chests—may gradually be

coming to an end, and that, in some

places and for some forms, the mar-

ket is showing signs of a pulse.

“You still can’t sell a Pembroke

table to save your life,” Doig said.

“They’re still going down, and it’s

hard to give away card tables.”

Nevertheless he thinks that, overall,

things are starting to look up.

Doig is ideally placed to sense

shifts in the market. Although he

does some shows, he has always

considered himself a picker. “I deal

with a half-dozen to a dozen deal-

ers who do everything from East

Side [the Winter Antiques Show in

New York City] to hole-in-the-wall

shows,” he said. When the market

turns sour, he feels it immediately

because dealers stop buying.

Lately, however, at least some

dealers are buying. He said, “It’s

coming back.” He is also seeing

better results at auctions. “We buy a

lot at auction. Prices are spotty but

trending upward,” he said.

(When Doig employs the term

“we,” he said he means “the royal

we.” The name of his wife, Karen,

has always been associated with the

business, but, as Doig explained,

her time is occupied by her career

as a visiting nurse. The official

name of the business, Karen Alex-

ander Antiques, Inc., combines her

first name with his middle name,

Alexander—that’s why everybody

calls him Sandy. His first name is

John.)

Doig has connections with some

dealers in the South and sees evi-

dence of more activity there than in

the Northeast. “One of my best cus-

tomers is in Virginia. He sold fif-

teen to twenty chests in the lower to

midrange during the last year or so.

I’ve got two or three dealers in the

Washington, D.C., area, and they’re

buying.”

Doig is also connected to the

southern market though his son,

John, who operates a furniture res-

toration business in Beaufort, South

Carolina. About a year ago, John

moved his business from Litchfield,

Connecticut, to Beaufort and Doig

père

said he immediately picked

up business from Charleston and

Savannah dealers. “They’re far

more active than up here,” Doig

said.

He added that other dealers, such

as his friend Ian McKelvey, are

finding the South to be a more con-

genial market than the Northeast.

He said, “Ian McKelvey went down

to Texas with Mario Pollo to do a

show, and he said it’s a different

world. They sold over sixty pieces.”

Doig’s favorite pieces, he said,

are “renditions of formal forms in

native hardwoods—cherry, maple,

and—although less so—birch. I’ve

become especially fond of Con-

necticut River valley pieces includ-

ing more rural examples up in Ver-

mont and New Hampshire.” He has

always gravitated toward smaller

items—candlestands, small tables,

chairs, inlaid boxes, tea caddies.

“I’ve never done much with high-

boys and tall chests,” he noted.

He also has a fondness for Fed-

eral looking glasses. “In my career

I’ve done maybe a thousand or at

least more than five hundred. We

did fifty or sixty Federal mirrors a

year.” He’s particularly interested

in the reverse-painted tablets in

tabernacle mirrors. “I’d like to do a

book just on Federal glass panels,”

he said. “They’re as good as any

folk art.”

Doig said he no longer does the

volume he once did. “I’m seven-

ty-two and have kind of scaled

back. I used to do four to five times

what I do now.” The luxury of tak-

ing it easy is “thanks to my wife

who continues to work.”

Doig had no particular interest

in antiques when he was growing

up in Ridgewood, New Jersey. He

said, “My father was from Scotland

and my mother was from northern

Maine, and we had not an antique

in the house.” He got a degree in

economics from Bowdoin College

and an MBA from Rutgers Univer-

sity. He spent two years in the army

but did not have to go to Vietnam.

He was in a transportation unit.

“I did port studies,” he said. He

became a certified public accoun-

tant (CPA) and went to work in the

tax department of Price Waterhouse

in Manhattan.

His first interest in anything that

might qualify as “old stuff” devel-

oped when he and a Bowdoin friend

named Jack Gazlay bought a boat

together. “It was an eighty-foot

yacht that needed total restoration,”

Doig said. The purchase allowed

them to live in a way that most

New Yorkers can only dream about.

They docked at the 79th Street boat

basin on the West Side of Manhat-

tan. Doig said, “It was the cheapest

place you could live in New York.

The mooring was a hundred and

sixty dollars a month with electric

and two covered parking spaces.”

TWO COVERED PARKING

SPACES! The ultimate New York

City luxury.

As they moved up the corporate

ladder with increased travel and

responsibilities, Doig and Gazlay

sold the boat and bought an 1850s

house in Saddle River, New Jersey.

“Boats take a lot of time,” Doig

said.

That led to an unexpected

involvement with other “old stuff.”

The sellers of the house, who were

moving to Florida, asked if the

young men would mind keeping

the furniture for six months, which

they were delighted to do. “When

you move off a boat, you have no

furniture,” Doig said. “It was all

antiques.” The owners’ interior

décor served as a template for how

to furnish a house. “At garage sales

we replaced pieces one by one,” he

said.

Then Sandy married Karen. They

bought out the partner and discov-

ered that they liked working with

old furniture so much that they both

took Sotheby’s restoration course,

which was then run by John Stair.

Eventually Sandy changed jobs,

joining a Connecticut firm that

developed tax shelters based on his-

toric restoration tax credits awarded

for turning old buildings into resi-

dential complexes. The firm, for

example, developed two big former

mills in Norwich—Falls Mill and

Indian Leap Mill. The employment

switch prompted the Doigs’ move

to Somers. Sandy’s office was in

Farmington, and the family wanted

In the Trade

Sandy Doig, Somers, Connecticut

by Frank Donegan

“Prices are spotty

but trending

upward.”

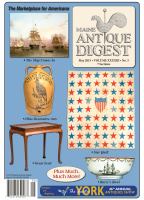

Sandy Doig in his basement workshop. In good weather he

works in his barn. He thinks the two-drawer stand is from the

south shore of Massachusetts. “It has the thinner stock that

they use there.” He’s asking $450 for it. “Eight years ago it

would have been nine hundred,” he said.

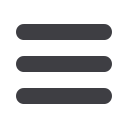

This one-drawer cherry bowfront console table with nice

inlay was on hold when we visited.

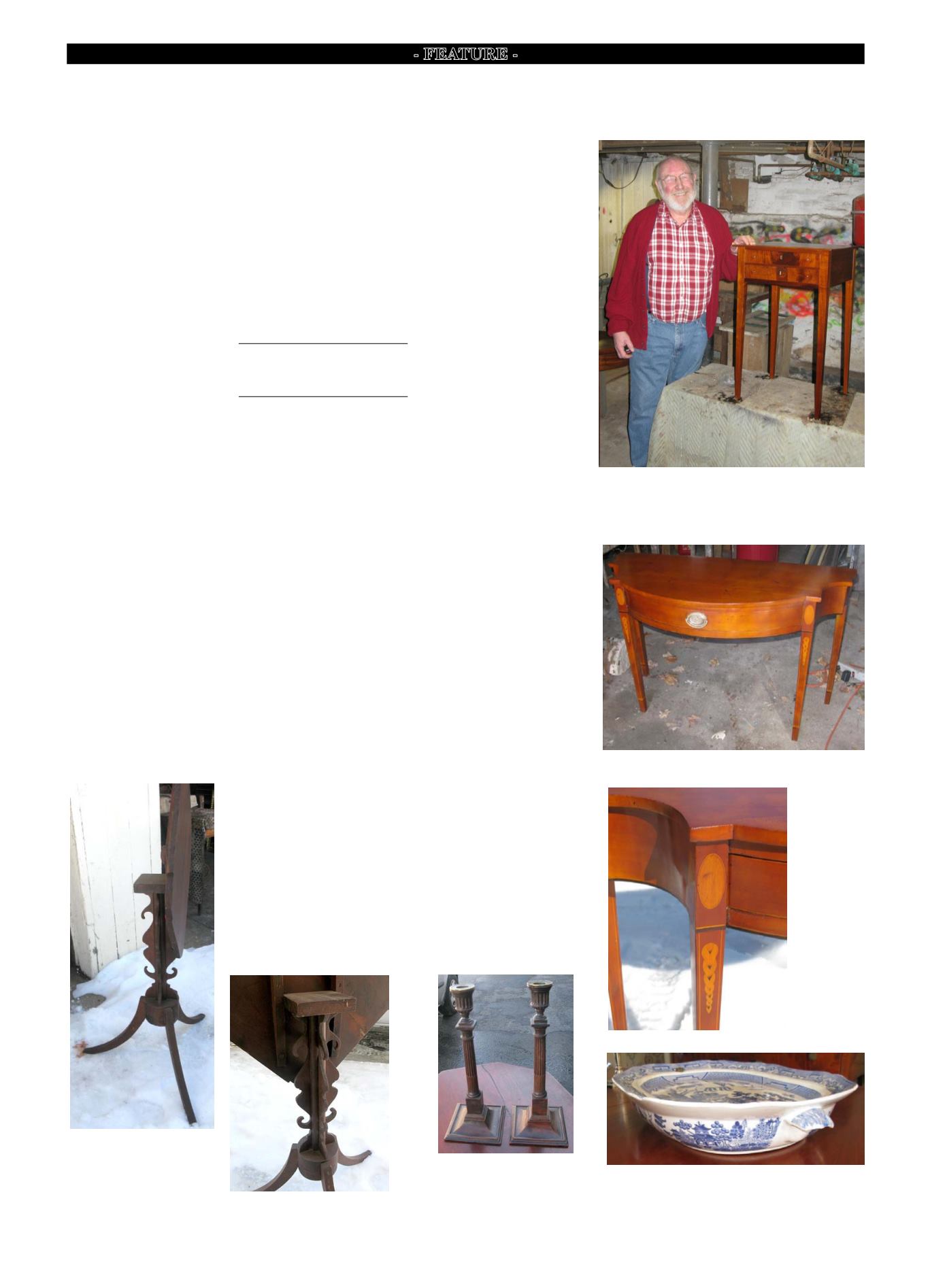

Inlay on the

cherry console

table. “This is

exactly the type

of thing I love,”

he said.

“This is the wildest Federal can-

dlestand you’ll ever see,” Doig

said. It’s cherry with thin fins

resembling miniature Federal

backsplashes that protrude from

the rod-like standard. It’s priced

at $550.

Detail of the cherry candlestand.

Pair of English mahogany can-

dlesticks, $325. Back in the

1990s, nice pairs of sticks like

these, with period bobeches, sold

for hundreds of dollars more.

The large blue Staffordshire warming plate is marked

“Copeland & Garrett,” which dates it to between 1833

and 1847. It’s 22" long and $275. “It’s the biggest I’ve ever

seen,” Doig said.