6-D Maine Antique Digest, May 2015

- FEATURE -

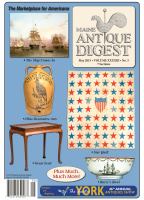

Giovanni Domenico Cassini’s

Carte de la Lune

of 1679. There is

a small hole at the centre where

once it was folded and there are

some slight damp marks and mar-

ginal staining, but it is a great

rarity and was sold last December

for $127,445 by Sotheby’s Paris.

Also shown is a detail that reveals

the face of a woman, a mysteri-

ous “Moon Maiden” who is now

widely believed to be Cassini’s

wife, Geneviève de Laistre.

E

ight years of careful

telescopic observations,

studying the moon in all

its phases, were required before

a remarkable and remarkably

accurate engraved image of the

surface of our closest celestial

neighbour was, one Saturday

in February 1679, presented by

the astronomer Jean-Dominique

Cassini for the approval of the

members of the Académie des

Sciences in Paris.

The details recorded in large

numbers of preparatory drawings

had been painstakingly trans-

ferred onto an engraved copper

plate to produce a print that has

earned a special place in the his-

tory of lunar cartography, but

an example of Cassini’s

Carte

de la Lune

sold for $127,445 by

Sotheby’s Paris on December

18, 2014, marked what is prob-

ably its first ever auction appear-

ance of the original, large-scale

version of 21" diameter.

Smaller versions were pro-

duced at a later date, but it seems

that very few prints were made

at the time from the original

full-size copper plate (long ago

melted down for reuse) and aside

from the example that emerged

in this French sale, just five or

six others are recorded.

There is one in the Observa-

toire de Paris (where 57 of the

original drawings made by or for

Cassini now reside); another two

are in the Bibliothèque Nationale

de France, again in Paris; and the

collections of the Royal Astro-

nomical Society in London and

the Harry Ransom Humanities

Research Center at the University

of Texas in Austin each have a

copy. It is also thought that there

may be one in the Osservatorio

Astronomico di Brera in Milan.

Cassini’s detailed depiction

of the moon’s surface, accom-

plished with the assistance of

Sébastien Leclerc and Jean Pati-

gny, who had produced the many

preparatory drawings, remained

unrivalled for some 200 years.

It was only when good qual-

ity photographic images were

obtained in the last years of the

19th century that this engraved

chart was truly bettered.

There are, however, two fea-

tures on Cassini’s moon that can-

not be seen in the finest of pho-

tographs. In the Sea of Serenity

there appears a large heart and

in the Promontory of Heraclides

can be seen the face of a beauti-

ful woman.

In an article on “The Moon

Maiden in Cassini’s Map” that

was published in a 2003 issue of

L’Astronomie

, Françoise Launay

of the Observatoire de Paris sug-

gested that the Moon Maiden

is in fact an image of Cassini’s

wife, Geneviève de Laistre. This

hypothesis is made even more

likely, says Launay, by the fact

that there exists in a French

museum a portrait of Geneviève

by Jean-Baptiste Patigny, the son

of Cassini’s collaborator on the

lunar map.

Cassini’s moon, it would

appear, was both a landmark in

lunar cartography and a declara-

tion of love—and around two cen-

turies later his romantic gesture

even found its way into one of the

earlier works of science fiction.

In Jules Verne’s

Autour de la

lune

(usually known in English

as

Around the Moon

), Captain

Nicholl and Impey Barbicane

are the rival members of the Gun

Club in Baltimore who, along

with Michel Ardan, a French

poet, crew a projectile that is

dramatically fired towards the

moon by a giant gun.

At one point, their conversa-

tion on the lunar features they are

observing includes the words,

“C’est la mer de la Sérénité

au-dessus de laquelle se penche

la jeune fille….”

The Italian-born astronomer

Giovanni Domenico Cassini had

been invited to come and work

in Paris by Louis XIV, acting on

the advice of his finance minis-

ter, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, and

there he was appointed director

of the Observatoire de Paris.

Cassini took French nationality

in 1672 and in the following year

married Geneviève de Laistre.

Cassini discovered four of the

satellites of Saturn and noted the

division in its rings, a feature

which was named for him. His

name is also commemorated in

the Cassini-Huygens orbiter that

has for over ten years now been

sending back information about

Saturn.

Letter from London

by Ian McKay,

<ianmckay1@btinternet.com>

T

his May selection kicks off with a double MM, a

sighting of a “Moon Maiden,” and there are more Ms

in a charming Exmoor landscape by Munnings and

a mosaic mask that turned Greek tragedy to saleroom joy.

A wonderful collection of old carriages and sleighs; an

Egyptian bronze cat that was almost thrown away in a

house clearance; a Hunnic gold collar; a silver battleship;

Fabergé cornflowers; and a picture of a rain-soaked angler

copied by Charlotte Brontë from a favourite book round

out this “Letter.”

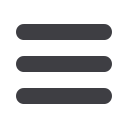

he Coming of Spring

, a marble figure of a

nymph made in Florence in the last quarter of

the 19th century, is the work of one of those

many expatriate American sculptors who found

their way to Italy to study the works of the Renais-

sance and Baroque periods, along with those of

their European contemporaries.

William Couper (1853-1942) was born in Vir-

ginia, studied at the Cooper Institute in New York

and, after visiting Munich in 1874, moved quickly

on to Italy. There, apprenticed to Thomas Ball,

he produced the portrait busts, mythological and

allegorical figures, small relief sculptures, and

so-called “ideal” works—of which this nymph is

an example—that were fashionable with affluent

Grand Tourists.

A plaster version of

The Coming of Spring

was

shown in Paris and London in 1885 before end-

ing up with Tiffany & Co. in New York City the

following year. Before pitching up there, it had

been described by a Florence-based reporter for

the

Boston Transcript

as “…a beautiful floating

or flying figure, bearing a wreath of flowers… so

delicate that one wonders if she touches the flow-

ers and leaves over which she is being borne by a

light zephyr.”

In 1995, as part of a New Mexico estate, this

marble made $96,000 in a Christie’s New York

sale and it came to auction in London on March of

this year from a Dallas estate. In a March 11 “Opu-

lent Eye” sale of European furniture, sculpture,

and works of art at Christie’s, it sold at $296,225.

Part of a February 24 auction held by Sothe-

by’s in which lots were characterised in the sale

title as being “Of Royal and Noble Descent,” the

Nymphenburg porcelain

réchaud

, or portable

stove, seen above was something that had a doubly

noble pedigree.

It came to sale in London from the collections

of an unnamed “German Nobleman,” but when it

was last sold, in their Amsterdam rooms in 2001,

it was clearly identified as the property of Prince

Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, for whom the phoenix

rising from the flames that serves as a finial to the

domed cover offered more than just a reference to

the purpose of the piece—keeping food or drinks

warm. In the 1750s, shortly before the piece was

made, circa 1765, Duke Philip Ernest zu Hohenlo-

he-Bartenstein had founded a private family Order

of the Phoenix.

Standing a little over 13½" high and probably

modelled by Johann B. Häringer, it is a rare item,

known only in a very few plain white and painted

examples. One of the four that fall into the latter cat-

egory is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

On its return to the salerooms, this example,

complete with small handled cup and burner, real-

ised $65,640.

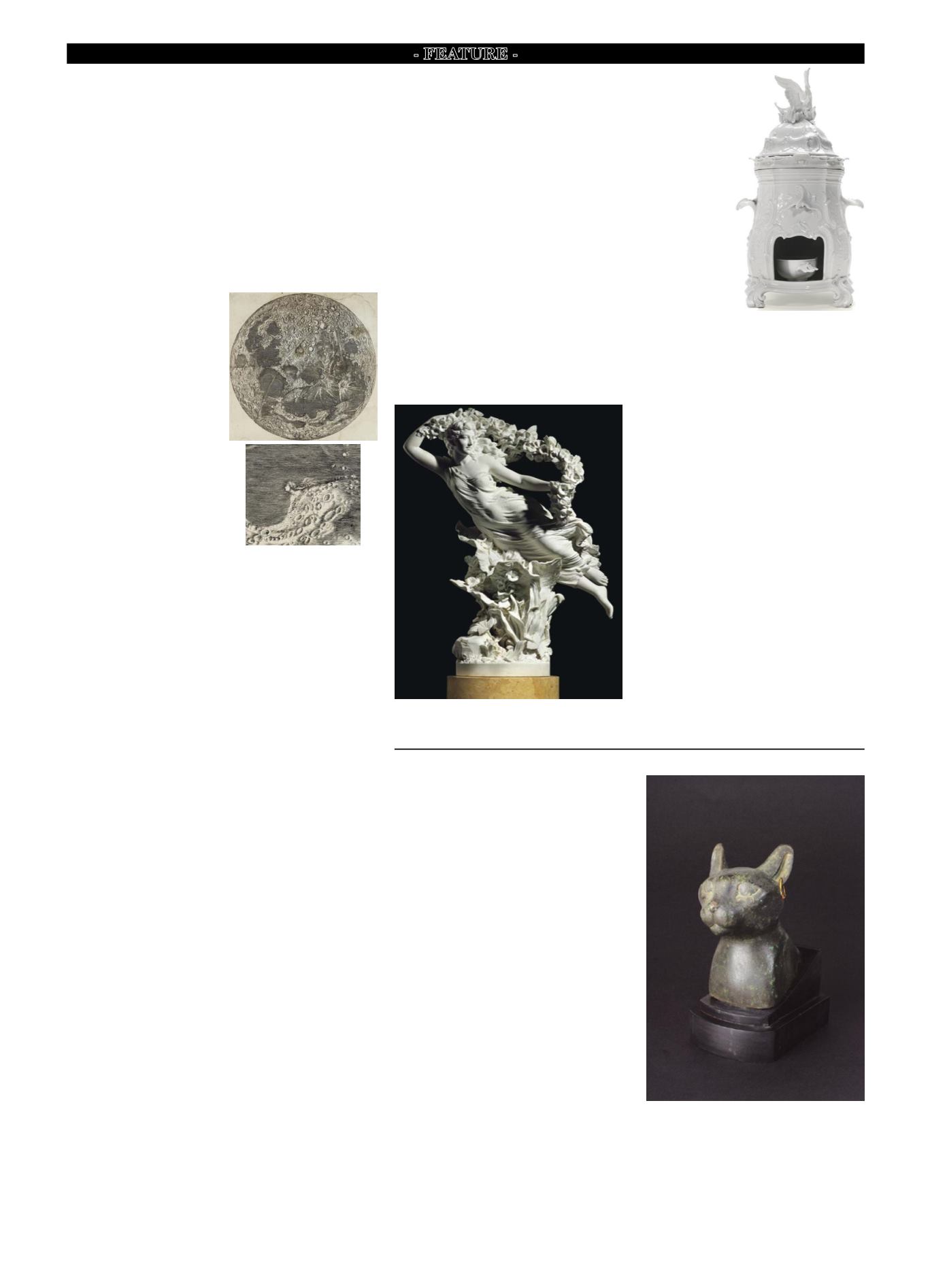

Y

et another of those irresistible “we didn’t

know it was valuable and were about to

throw it out with the garbage” stories

emerged from a February 19 sale held by David

Lay, a friendly country saleroom located right

down in the southwest “boot” of England, in the

Cornish coastal town of Penzance.

The life-size bronze head of a cat seen here was

sitting in front of an old gas fire (or on a mantel-

piece over the fire, depending on which of the

many media reports you read) when clearance

began of a local cottage that David Lay’s fortunate

consignors had inherited.

At one stage it seemed destined to be thrown

in a skip, but the local auctioneers were called

in and the 7" high bronze cat found itself instead

being taken up to the British Museum in London,

where it was authenticated as an Egyptian piece

and dated to the 26th Dynasty (664-525 B.C.). It

subsequently emerged that it could be linked with

a close relation of the consignors, the late Douglas

Liddell. A former managing director of Spink &

Sons, the well-known U.K. firm of antiques, antiq-

uities, and numismatic dealers and auctioneers, he

had retired to Cornwall and died there in 2003.

The gold hoop earrings that the cat wears may

be original, said an auction house blog, as by the

time this one was made, mummified cats were

sometimes buried in bronze caskets in special

cemeteries, and feline statuettes, such as this—

representations of the goddess Bastet—were being

presented as votive offerings at temples and some-

times placed in tombs to accompany their owners

into the afterlife.

On sale day, it carried a cautious estimate of

$7500/15,000, but eight telephone lines were in

action and in the end it went to a London dealer

for $92,320.

PS: I must admit to borrowing and adapting the

headline to this piece from one written by one of

my colleagues on the U.K. weekly

Antiques Trade

Gazette

.

That’s No Moon Maiden, That’s My Wife

Concerning Nymphs and Nymphenburg

T

The Nymphenburg por-

celain

réchaud

of circa

1765 which sold for

$65,640 at Sotheby’s.

American sculptor William Couper’s marble

nymph,

The Coming of Spring

, sold for $296,225

by Christie’s.

The life-size Egyptian bronze head of a cat, found

whilst clearing out an old Cornish cottage, sold for

$92,320.

A $90,000 Penzance Purr-chase

A full-scale version

of the marble is in the

National Memorial Park

at Falls Church, Vir-

ginia, but this 32¼"

high marble version

on a later yellow sca-

gliola pedestal is

first documented

in the collection of

the American ship-

ping, iron, railroad,

and mining mag-

nate J.J. Hagerman.

In declining health,

he had travelled to

Europe in the 1880s

and in Italy sculp-

tors such as Couper

had ateliers where

tourists could com-

mission portrait busts

or full-scale marble

works from the plas-

ter reductions on display.