Maine Antique Digest, March 2015 11-A

Sotheby’s October 21, 2008, sale of

her estate totaled $5,665,006. Sothe-

by’s October 29, 2014, “Part II” sale

of her estate totaled $2,045,668.

The suit claims that Gallery 63 ad-

vised the Knispels in 1994 in connec-

tion with the sale that it would arrange

to have the painting appraised by an

“expert” in the field, Laurence Casper

(d. 2014) and Casper Fine Arts. The

estate of Laurence Casper and Casper

Fine Art & Appraisals are named as

defendants in the suit.

Casper examined the painting in

October 1994, the suit claims. His

written appraisal reads, “[A]s request-

ed...I have examined the painting in

detail and find the brush strokes, the

painting texture and the draftsmanship

consistent with Rockwell’s technique.

The type of faces and expressions

are typical of his characters in other

paintings as well. The painting is not

recorded and I believe the painting

was commissioned for an advertise-

ment and never used. In my opinion,

[the Painting] is an original by Nor-

man Rockwell with all the humor and

artistic quality that Rockwell created

in all his works.”

With the appraisal in hand, the Knis-

pels completed the purchase, and

the painting has hung on their wall

ever since. The Knispels insured the

painting, and by February 27, 2013,

the retail replacement value was

$1,750,000, “pending receipt of ev-

idence of authenticity.” Chubb, the

insurance carrier, required that the

painting, along with other works of art

in the Knispel collection, be examined

to determine authenticity and current

value.

This time, New York Fine Art Ap-

praisers examined the painting, and

the findings were not good. The ap-

praisal report noted that the painting

is not an “original oil on canvas by

Norman Rockwell.” Instead it was

determined to be an illustration for

a Mobil Oil advertisement by Con-

necticut and Massachusetts illustrator

and commercial artist Harold An-

derson (1894-1973), titled

Patching

Pants

. Worse, the report noted that

the “Rockwell signature was painted

over the signature of the original artist

and that this alteration is (and should

have been) open and obvious to any

appraiser with training and experience

similar to Casper’s,” the suit claims.

The Knispels have been advised that

the painting is now valued at only

$20,000.

(The highest auction price for a

Harold Anderson we could find was

$17,500, paid at Heritage Auctions in

October 2012 for

Peace on Earth

.)

The Knispels are charging breach of

contract, negligence, fraud, and viola-

tion of New Jersey’s Consumer Fraud

Act.

No Regrets

by George Bulanda

O

ne of Édith Piaf’s big hits

was “

Non, je ne regrette

rien

” (No, I regret nothing), but I

doubt the French chanteuse was

a collector.

All collectors and dealers have

regrets about purchases, some of

them costly. If they deny they’ve

made mistakes, they’re either

too embarrassed to admit them

or think the admission will erode

their credibility.

We have a habit of talking

ruefully about the ones that got

away, the great antiques that,

because of a Hamlet-like inde-

cision, escaped our clutches and

landed in someone else’s hands.

We knew they were good, rare,

or valuable, but we let them slip

away.

Yet, how about the pieces we

wish

had

gotten away, the ob-

jects we paid too much for or

bought before we had sufficient

knowledge about a particular

antique? Maybe, early on in our

collecting enthusiasm, we were

sweet-talked into a purchase by

a wily dealer or an insufficiently

educated owner, or perhaps we

just got swept away at an auction

and bid far higher than what an

item was worth.

Sometimes we convince our-

selves that an object is authentic

or rare because we want so much

to believe it, despite evidence

to the contrary. Nobody likes

to talk about those lunkheaded

buys, but in the spirit of facing

the still-fresh new year, I’ll come

clean about my, let’s say, “mis-

calculations.”

There’s an anatomical chain

reaction that’s typical of most

antiques

transactions—eye-

heart-brain. We have all heard

of people with “a good eye” who

can spot quality or rarity. If it’s

pleasing to the eye, the heart is

the next organ to take over. Do

I really love it? If not, that’s as

far as it goes, but if so, the brain

is the final organ to sound off.

Sometimes it’s an alarm. Yes,

the piece is pretty, but it’s a fake,

made to look old. Or, certainly it

has charm, but the craftsmanship

is second-rate. Finally, the mind

has to decide if the asking price

is fair.

The big problem comes when

the heart refuses to listen to the

brain. Don’t underestimate the

pull of sentiment or romance;

it’s made fools of us all. As Edna

St. Vincent Millay wrote at the

end of her Sonnet 29, “Pity me

that the heart is slow to learn /

When the swift mind beholds at

every turn.”

Atop my piano sits a carved

wood Buddha, black-lacquered

and showing traces of red and

gold paint. If only he could talk

he could tell me plenty, such as

when he was actually made and

by whom. An ad for an estate

sale mentioned that the carving

dated from the 16th century with

a certificate of authenticity to ac-

company it. But when I arrived

at the sale and saw the Mon-style

figure, my skepticism kicked

into high gear. Why wasn’t the

lacquer crackled with time, and

why wasn’t the exposed wood

at the back darkened with age?

And may I please see that “cer-

tificate of authenticity”?

When it was presented to me,

I almost gasped. There was no

address or phone number of the

company that had authenticated

the piece, only the illegible sig-

nature of someone who verified

that it was “Mon Style, Pagan

Period,” dating from the 16th

century and a “Genuine Bur-

mese Antique.” Oh, and that

Old English typeface really lent

credence! As tennis great John

McEnroe would say, “Are you

serious?”

When I voiced my reserva-

tions, the woman running the

sale countered with a non se-

quitur: “This man could afford

almost anything.” Perhaps, but

wealth doesn’t shield one from

naiveté and vulnerability. She

produced a bill of sale from a

long-gone shop in Detroit. The

man paid $2250 for it in 1982,

and the estate sale company was

asking, I believe, $950.

There were more red flags

than at a matadors’ convention,

but there was also something I

liked about this contemplative

figure, so seraphic and serene.

In my mind, I began to make ex-

cuses. Maybe the wood wasn’t

darkened in the back because it

was against a wall for centuries.

And perhaps the lacquer wasn’t

crackled because of a more con-

stant climate in Burma. Against

my better judgment, I bought it,

though I was able to get the price

reduced to $800.

In time a clearer head pre-

vailed. I suspect it actually dates

from the early 20th century, ages

later than what was claimed, and

was probably worth about a third

of the amount I paid.

On another occasion I bought a

boudoir lamp, the base of which

is made of carved ivory; this

was well before the flap about

buying and selling ivory. The

antiques shop owner guessed

the carving was done in the late

19th century and later made into

a lamp. I didn’t doubt it and still

don’t today. It sits on a rosewood

base with an amethyst implant-

ed in the center. It had a cheap,

unsuitable shade, so I replaced

it with an expensive Asian-style

silk one. I told a dealer friend

who specializes in Asian piec-

es about it, and he asked to see

it. He took one glance and gri-

maced. “That’s an inferior piece

of carving,” he weighed in with

crushing authority. “Nice shade,

though.” Ouch.

He suggested I go back to the

store and ask for my money back

($500), but I was too humiliated.

Why had I acted so impulsively?

Why hadn’t I compared it to su-

perior pieces of ivory I’d seen? It

was about 125 years old, but age

doesn’t always translate to qual-

ity. Too late. It sits on top of an

early 19th-century painted Chi-

nese cabinet as a reminder—a

lesson, really—of a bad move on

my part.

Another flub almost happened

at an auction. I got caught up in

the moment, but when the heat

was on, I braked instead of ac-

celerated—to my credit. I was in

a battle with a telephone bidder

over a circa 1900 painting by

an accomplished Detroit artist.

I even had a place picked out

where it would hang. But the

bidding escalated into a region

that was too steep, well beyond

the estimate and what the artist’s

works were selling for at the

time.

“What are you doing?” I re-

proached myself. “And don’t

forget the buyer’s premium and

taxes,” my inner voice warned.

When it was my turn again to

counterbid, I kept the paddle on

my lap. I felt defeated, but also

oddly triumphant.

About a year later I saw the

painting at a local antiques shop

for an even higher price than

what it sold for at auction.

“So you’re the one I was bid-

ding against,” I said to the pro-

prietor.

He admitted he was and of-

fered to let me have it for what

he paid, including the buyer’s

premium and taxes.

“No thanks,” I said. “I think

you spent too much.”

You see, he was the same fel-

low who had sold me the poorly

carved ivory lamp. I didn’t ex-

actly feel vindicated, but as an

antiques buyer, I did go away

feeling smarter.

P

ewter & Wood Antiques’ ninth annual

Alzheimer’s Silent Auction Benefit for

Research is being held March 21 in Cave Creek,

Arizona. All items are donated by customers,

dealers, and supporters. Donations of antiques

are currently being accepted through March 13.

Donations are tax deductible, and theAlzheimer’s

Association will mail out letters directly to donors

after the benefit. If you are interested in making

a donation, contact Barb Johnson for a mailing

address.

An on-line catalog with photographs will

be available beginning March 16 on Pewter &

Wood’s Web site

(www.pewterandwoodantiques.

com). Bidding may be done in person as well as

by phone. Successful bids are payable by check

made out to Alzheimer’s Association Desert

Southwest, memo: Research. Direct all questions

to Barb Johnson, Pewter & Wood Antiques, at

(602) 677-5686.

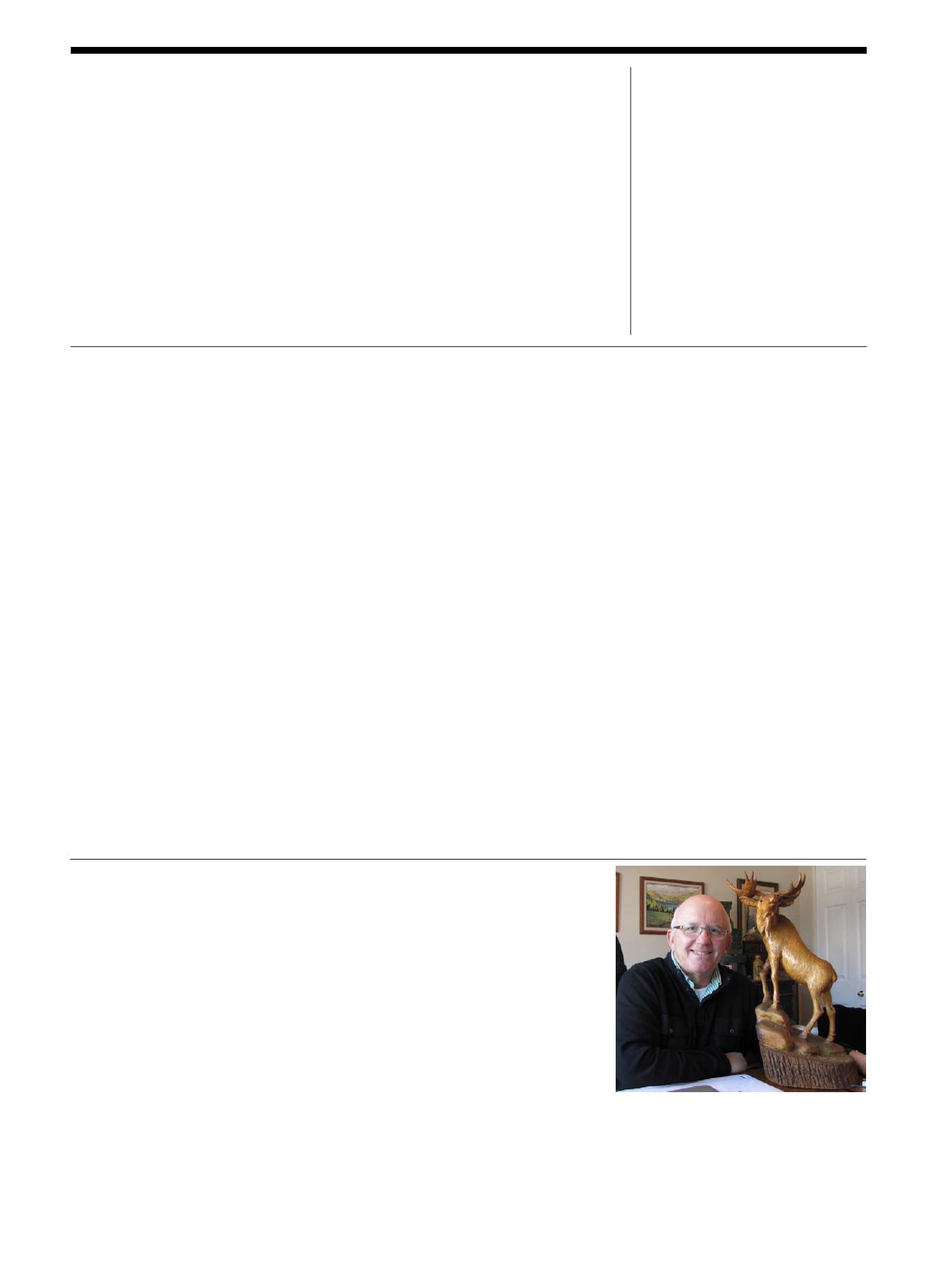

by Shaun Markey

I

n the realm of folk art, woodcarving

is a popular collectible. The Ottawa

Valley in Canada was home to a

number of folk artists who worked

in wood. One in particular, Charles

Vollrath (1870-1952) of Chalk River,

Ontario, was immensely talented,

and his carvings of wildlife, angels,

and other religious items are highly

sought after by collectors. Vollrath

was active in the 1930s and ’40s

producing woodcarvings, which he

sold to tourists at a roadside stand.

From that small stand, his carvings

were distributed throughout Canada,

the U.S., and beyond.

Recently, Chad Vollrath of Sarnia,

Ontario, a grandson of Vollrath, read

my book

Folk Art in the Attic

, which

included a passage about his grand-

father in a chapter about folk artists.

As it turned out, he wanted to find

a carving by his grandfather to give

to his father as a gift. It was nice to

receive the e-mail, but unfortunately

I knew his search was going to be a

difficult one. I certainly didn’t have

a Vollrath carving in my collection,

and it had been several years since I

had seen one, but I told him I would

keep my eyes open and would let

him know if I came across any ex-

amples of his grandfather’s art.

A few months went by. Then one

day, I decided to make the rounds

of a few antiques stores downtown.

Popping in once a week to review a

dealer’s inventory is standard proce-

dure for almost all collectors.

I included one store that I visit

only infrequently. I climbed the stairs

to the second level, said hello to the

owner/dealer, and proceeded to wan-

der through the maze of rooms piled

high with all manner of books, paint-

ings, antiques, and various collect-

ibles. Some antiques dealers prefer

the “jumble” approach. Pile the stuff

everywhere and anywhere within

the shop, and let customers have the

fun and the challenge of searching

through the store looking for a par-

ticular item. This dealer takes that

model to a whole new level.

I wandered here and there through

his store and returned to where he

was seated in a chair near the en-

trance. We chatted for a few mo-

ments about the state of the antiques

business in general. It was about

two o’clock in the afternoon. I was

standing next to a table brimming

with small antiques. My left foot was

touching a stack of paintings piled on

the floor. Light streamed in through

the dusty windows behind me.

Just then, an elderly man emerged

from the entrance hallway and took

a few steps into the shop area, where

he paused for a moment in front of

the two of us. He was breathing a lit-

tle heavily from coming up the long

flight of stairs that led to the shop. He

wore a beige overcoat that seemed a

few sizes too large for him. In his left

hand he was carrying a paper shop-

ping bag. Jutting out from the top

of the bag were the antlers and the

head of a very large woodcarving of

a moose.

My eyes immediately locked on to

the bag. I blurted out, “Hey, is that a

Vollrath or Patterson carving?” (Abe

Patterson [1899-1969] was another

very talented carver. His work is also

highly sought after.) Undeterred by

my question, the old man crossed in

front of me and sat down heavily in

Searching for the Works of a Master Woodcarver—Charles Vollrath

Antiques to Help Beat

Alzheimer’s

the armchair across from the dealer. He placed the bag

in front of him on the floor. Slowly, he reached down

and extracted the piece from the bag and held it briefly

in the air in front of him.

I knew immediately this was an impressive carving

by Charles Vollrath. Of course, I was anxious to buy it.

The dealer reached over and took the carving and began

to examine it. The old man explained that while bring-

ing the piece down to the store he had broken one of the

The author and the circa 1930 carving, which stands about

2' high and is carved from a single block of wood.