12-D Maine Antique Digest, March 2015

- FEATURE -

A

triumphant end of year sale

as far as Sotheby’s were con-

cerned was one titled “Daughter

of History: Mary Soames and the

Legacy of Churchill,” held in a

glare of publicity on December

17, 2014.

Born in 1922, the youngest

child of Winston and Clementine

Churchill, Mary was the only

one of their children to grow up

at Churchill’s beloved home at

Chartwell in Kent—enjoying a

“golden childhood” in the words

of her own son—but during

World War II she served in the

Auxiliary Territorial Service and

acted as one of her father’s close

confidantes and aides-de-camp,

a role that made her witness to

many important wartime meet-

ings and brought her into contact

with such other major figures as

Eisenhower and Montgomery,

Roosevelt, and Stalin.

After the war she married

Christopher Soames, a Cold-

stream Guards officer who

became a politician and subse-

quently a diplomat. Mary, who

like her father before her wrote

an acclaimed biography of a par-

ent, in her case her mother, died

in 2014, and the 255 lots that

made up this enormously suc-

cessful sale, a selection from the

contents of her London home,

proved an irresistible attraction.

Even the catalogues sold out.

Over 4000 people viewed the

sale, some 900 people from 47

different countries registered

to bid, either in the room or on

line—two-thirds of them new to

Sotheby’s—and the result was a

“white glove” sale, with all lots

sold and, more significantly, all

bar a small proportion of them

selling above estimate to raise a

total of $24.25 million.

Of the “Top Ten” lots, all bar

one were paintings by or of her

father, and right at the top of

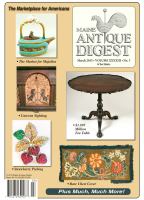

the list was Winston’s 1932 oil

The Goldfish Pool at Chartwell

seen upper right. One of 15 of

his paintings in the sale, this was

not of course in the same league

as one of Monet’s famous water

garden oils, but it was described

by Sotheby’s as “undoubtedly

Churchill’s masterpiece” of that

decade, and in postwar years he

certainly selected it for inclusion

in his 1948 book,

Painting as a

Pastime

.

Agift from her father and once

prominently displayed over the

mantelpiece in the drawing-room

of her home, it more than trebled

the estimate to sell at $2,767,600

and in so doing became the most

expensive painting by Churchill

ever sold at auction*.

Though it is something that

is not easy to define, substanti-

ate, or justify, it might also be

claimed as marking out Chur-

chill as the world’s best-selling

amateur artist. This tentative and

perhaps irrelevant claim may of

course be disputed, challenged,

dismissed, or ignored by

M.A.D.

readers.

The pictures were primarily,

if not entirely sold to private

buyers, and this top lot went to

an English collector, as did an

early (circa 1920) oil of

A Villa

at the Riviera

, which made a six

times estimate $1,040,300, but

Winston Churchill has a great

many American admirers and at

least five of the other best sell-

ing pictures by Churchill went to

American private buyers—four

at sums in excess of $1 mil-

lion.

Among them were an oil of

The Harbour, Cannes

dated to

circa 1933, another reminder that

the French Riviera was the Chur-

chills’ preferred holiday destina-

tion, which sold at $1,134,520,

and an English view, a 1920s

painting showing the cathedral

city of Wells in Somerset that

reached $1,096,830.

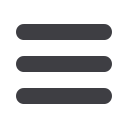

The landscape that I have cho-

sen to illustrate actually came

in at No. 10 on the best-sellers

list, but it is one that combines

two of Churchill’s off-duty pas-

times and passions—painting

and bricklaying. The 1937 oil

showing

The Weald of Kent

under Snow

, painted from Chart-

well, seen upper right, has as a

backdrop a wintery prospect of

the view across the Weald from

Churchill’s home at Chartwell,

near Westerham in Kent, but in

the foreground are some of the

walls that he built around the

kitchen gardens.

Thiswasapastime thatChurch-

ill found relaxing and far

removed from the worlds of war

and politics, though one that,

like painting, would also have

given him plenty of time to think

things through, and one of the

catalogue photographs shows

him hard at work on his walls,

trowel in hand and the trademark

cigar clamped firmly in place.

M

ade by al-Ahmar al-Nu-

jumi al-Rumi for the trea-

sury of an Ottoman Sultan,

Bayezid II, in the first decade of

the 16th century, the instrument

seen top left next page is one of

only two astrolabes recorded as

having been made especially for

this Turkish ruler—in fact, for

any Ottoman sultan. The other

one, made by Shukrallah Mukhis

Shirwani in the Persian style and

more ornately, even distinctively

decorated is in the Museum of

Islamic Art in Cairo.

The workmanship seen in this

recently sold brass instrument

was described by Sotheby’s in

the catalogue for an October 8,

2014, sale of Islamic works of

art as “competent,” but they also

observed that it was primarily an

instrument intended to be used

rather than just admired, and rep-

resents the beginning of a new

Ottoman tradition for more mod-

estly decorated astrolabes—a

tendency that had already been

seen in earlier Syrian pieces that

were made, or at least designed

by the astronomers themselves

rather than as presentation pieces

by professional craftsmen.

All other surviving Ottoman

astrolabes are of later date,

by at least a century, and the

Letter from London

by Ian McKay,

<ianmckay1@btinternet.com>

W

inston Churchill continues to attract

adulation and huge prices in the sales-

room, as one of the last of the old year

sales in London so clearly showed, but in this

selection he is joined in his staggering success

by the most expensive watch ever made, a $24

million “Supercomplication” sold in Geneva.

From other London sales come an old astrolabe,

recovered and restituted porcelain, portrait min-

iatures, Turk’s head cutlery, a marble Virgin, and

two youngsters on a fence. This month’s selec-

tion also includes a couple of lots that were not

to be found in prestigious salesroom venues of

central London and Geneva, but in two country

salesrooms. A corkscrew and a ship’s figurehead

that made big prices were both found in Essex.

A “Daughter of History” and the

Churchill Legacy

Pictures of, rather than by,

Churchill were led by Sir

Oswald Birley’s half-length por-

trait of Churchill wearing one of

the “siren” suits that he famously

adopted during World War II—a

one-piece garment initially

designed for easy use when

sirens sounded the need to seek

safety in air-raid shelters—but it

was painted in postwar years, in

1950. Estimated to sell for some-

thing in the region of $300,000,

it was secured by an anonymous

bidder for a much, much higher

$2,239,990.

This was far and away the

highest price ever seen for a Bir-

ley painting—the previous best

being $84,930 for a 1950 por-

trait of HRH Princess Elizabeth

of England that sold at Drew-

eatts & Bloomsbury Auctions

in London in 2014—but again I

have selected something a little

cheaper for illustration.

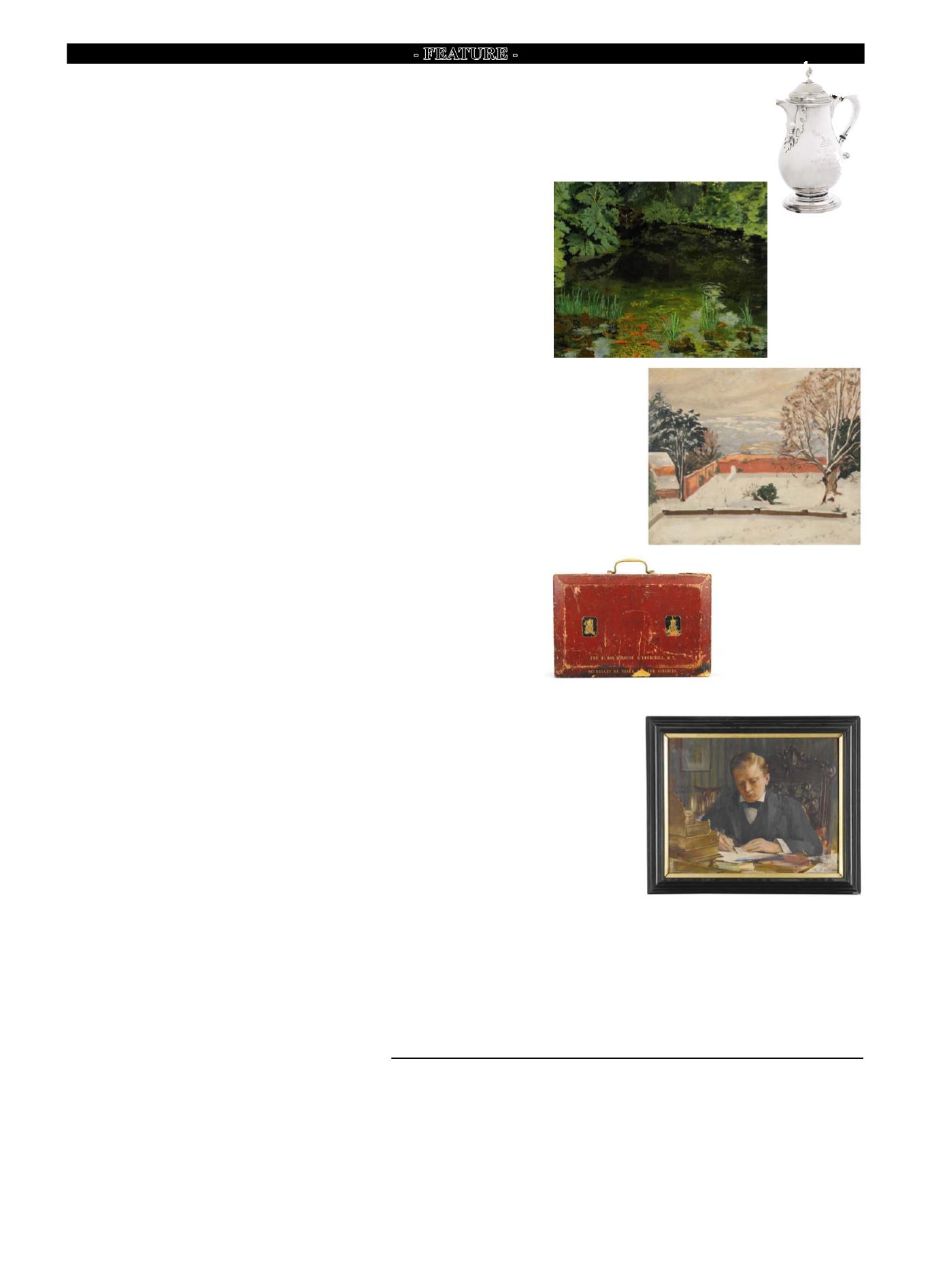

Seen bottom right is Edwin

Arthur Ward’s portrait of a much

younger Winston Churchill,

seated at a desk. This picture

dates from around 1900, but in

1886 Ward had painted a portrait

(still at Chartwell) of Church-

ill’s father, Lord Randolph

Spencer-Churchill (at the time

both Chancellor of the Exche-

quer and Leader of the House of

Commons), who is seen sitting

at the same desk, on the same

heavy oak chair, and dressed in

an identical black coat, waistcoat

and tie.

When this later picture was

painted, the young Winston was

engaged in writing a biography

of his father, something which

would have provided an apt con-

text for the commission itself

and might explain the close sim-

ilarities of its setting—though

he was also starting to make a

name for himself as a politician,

rather than as a writer and war

correspondent.

The pictures were not the

only lots that brought far, far

higher than expected bids in this

remarkable sale.

The silver jug pictured at top

right is a Comyns & Sons piece

hallmarked for 1942, but it was

a birthday gift presented to him

that same year by fellow mem-

bers of the War Cabinet and

intended to commemorate the

crucial Allied victory over Rom-

mel’s Afrika Korps in North

Africa, at El Alamein. Valued

by Sotheby’s at $6000/10,000, it

sold instead at $437,320!

The red leather dispatch box

seen above right dates from

Churchill’s short time as Sec-

retary of State for the Colonies

(1921-22) and was something

that sold for close on to 30 times

the suggested sum, at $248,890.

An Asprey burr yew and ivory

humidor of circa 1930 was a

reminder that, like her father,

Mary Soames was fond of cigars

and would compete with him as

to who could maintain the long-

est tip of ash. It sold at a huge

$33,370.

Among the signed photo-

Churchill’s

1932

oil painting of

The

Goldfish Pool at

Chartwell

, sold for

$2,767,600. Descen-

dants of the occu-

pants, Golden Orfe,

can still be seen at

Chartwell.

Winston Churchill’s

principal

hobbies

were painting and

bricklaying and this

oil, sold for $983,775,

shows a view across

the snow covered

kitchen gardens of

Chartwell and the

walls that he built to

surround them.

graphs, two that stand out are

one of Franklin D. Roosevelt

that the President gave to the

young Mary Churchill in 1943,

when she accompanied her

father to the first Quebec Con-

ference, and another of Eisen-

hower and Churchill that dates

from Churchill’s last visit to the

U.S.A. as Britain’s Prime Min-

ister, in the summer of 1954.

Modestly valued at just a few

thousand dollars apiece, they

sold for $51,035 and $58,885,

respectively.

*

As one of England’s most

famous sons, it is perhaps unsur-

prising that the most sought-af-

ter and expensive (as well as the

rarest) of Churchill’s pictures

have generally featured English

views or subjects, and the previ-

ous record of $2.03 million was

set in 2007 in the same rooms

for

Chartwell Landscape with

Sheep

.

Edwin

Arthur

Ward’s portrait of

a young Winston,

circa 1900, sold

for $192,360.

Dating from Churchill’s time as

Secretary of State for the Colo-

nies in the early 1920s, this bat-

tered red leather dispatch box

sold for $248,890 at Sotheby’s.

Distinctive red boxes such as

this have been used to hold state

documents since the 1840s, and

one of the oldest survivors, Wil-

liam Gladstone’s battered old

dispatch box, is to this day still

used by the Chancellor of the

Exchequer and held aloft by him

on Budget Day.

Inscribed “Egypt 1942…,” this silver jug was pre-

sented to Churchill by members of the War Cab-

inet to celebrate his birthday and, more impor-

tantly, the turning point in the war marked by the

Allies’ victories in North Africa. In a subsequent

speech, Churchill famously said of this victory,

“Now is not the end, it is not even the beginning

of the end. But it is perhaps, the end of the begin-

ning.” The jug sold for $437,320.

The Sultan’s Astrolabe—Made by “The Red One”