Maine Antique Digest, March 2015 13-D

- FEATURE -

auctioneers noted that of around

30 or so recorded examples,

none demonstrates any indica-

tion of having been specifically

influenced by the two that were

made for Bayezid II. His inter-

est in astronomy, however, was

well known and the institutions

of court

munajjims

(astrono-

mer-astrologers) and mosque

muwaqqits

(timekeepers) were

established in his time.

Bayezid II studied mathemat-

ics and astronomy under Miriam

Chelebi, grandson of Qadi Zade

al-Rumi, director of the obser-

vatory at Samarkand that was

founded by astronomer, math-

ematician, and Timurid ruler

Ulugh Beg in the first half of the

15th century. The sultan’s own

studies and commissions, com-

mentaries, etc., are all recorded,

as one would expect—but little

is known of the maker of this

astrolabe.

A craftsman whose name

means “the red one,” al-Ahmar

al-Nujumi al-Rumi may have

been a Turk from central Anato-

lia, and the epithet “al-Nujumi”

indicates that he was an astron-

omer, but he does not appear in

a recently published bio-bibli-

ographical survey of Ottoman

astronomers and their works.

This complex and rare instru-

ment, which measures 3¾" in

diameter, was sold at $1,547,890.

The early 16th-century astrolabe,

sold last October for $1.548 mil-

lion at Sotheby’s.

F

irst exhibited at the Rome Biennale of 1925, in

the section devoted to sacred art, and on Decem-

ber 11 last year sold for $230,050 at Sotheby’s,

Adolfo Wildt’s cream marble head of the

Vergine

,

also known as

Testina di Maria

, recalls one of his

earliest marbles, a

Vedova

, or

Widow

, of 1892—a

portrait of a woman with a scarf encircling her

face—that was in its turn inspired by a Canova bust

of a Vestal Virgin now in the Galleria d’Arte Mod-

erna in Milan.

Wildt’s model for the earlier bust of a widow was

actually his wife, Dina Boschi, which may seem a

touch morbid for a sculptor who was then only 24

and presumably not long married when he created

it, but then it seems he was known for his melan-

cholic temperament.

In this 1920s head, however, he simplified both

of those earlier prototypes and

focussed wholly on the face,

employing soft forms rather than

his more usual sharp lines and

angles. Wildt’s

Vergine

was also

shown in a New York exhibition

of Italian modern art in 1926 and

he is known to have produced at

least three versions within two

years.

This one was first owned by

Pia Scheiwiller, sister of the

publisher and art critic Giovanni

Scheiwiller, who had married

Wildt’s eldest daughter, Arte-

mia. It may have been a gift from

Giovanni and Artemia, if not

from Wildt himself, to the “Aunt

in Rome,” as Pia was known to

the family.

A Virgin for the “Aunt in Rome”?

At Sotheby’s on December 11,

Adolfo Wildt’s life-size head of

the Virgin, mounted on a veined

yellow marble slab—and seen

here full face and in profile—was

sold at $230,050.

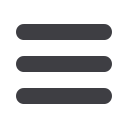

A

t a Sotheby’s Geneva sale

on November 11, 2014,

the gold watch seen at top right

became the most expensive time-

piece of any kind sold at auction

when bidding reached $24.016

million. It had in fact more than

doubled its own record of $11

million, set in 1999 in a Sothe-

by’s New York sale of Seth

Atwood’s Time Museum.

To be more precise, that was

the bid that secured it for Sheikh

Saud bin Mohammed al-Thani, a

member of Qatar’s ruling family

who, until 2005, when charges of

corruption were brought against

him and he was dismissed from

his post, had been both a prolific

private collector and from 1997,

Qatar’s minister of culture,

arts, and heritage. Many times

described as the world’s richest

and most powerful art collector,

he is reputed to have spent $1.5

billion in filling new museums

in Doha and, through bidding

extraordinary sums, had a dra-

matic and, for some, unwelcome

impact on the international auc-

tion market.

Prompted by news of his

death, a story in the November

17, 2014, issue of the

New York

Times

* states, “In 2012 a High

Court judge in London froze $15

million worth of Sheikh Saud’s

assets as part of a dispute over

unpaid bills to auction houses.

To pay the debt, he consigned

the Graves watch to Sotheby’s in

Geneva.”

It was sold on November 11,

two days after he died. On its

return to the salesrooms, it was

simply provenanced to a “pri-

vate collection.”

Commissioned in the mid-

“Complications,” Certainly—but Bidding Ticks

Up to $24 Million

1920s from Patek Philippe by

the New York City banker, boat-

ing enthusiast, and print collec-

tor, Henry Graves Jr., the watch

that came to be known as the

“Henry Graves Supercomplica-

tion” resulted from a round of

pocket-watch

one-upmanship

that Graves had indulged in with

James Ward Packard, the car

manufacturer.

Graves asked Patek Philippe to

conjure up the most complicated

watch ever made. They obliged

and seven years later he handed

over $15,000 for the “Supercom-

plication,” which is just under 3"

in diameter and 1½" thick, and

contains 920 separate compo-

nents, including 430 screws, 110

wheels, 120 mechanical levers

or parts, and 70 jewels that facil-

itate its 24 horological com-

plications—all packed into an

18-karat gold case and weighing

one pound, three ounces in all.

In 1989, to mark the compa-

ny’s 150th anniversary, Patek

Philippe did come up with a

33-complication watch, the

“Calibre 89,” but that one incor-

porated computer controlled

functions, and the Graves special

remains the most complicated

analog watch ever made.

For the more horologically

minded of

M.A.D.

readers, the

basic description is as follows:

“A gold, double dialled and dou-

ble open-faced, minute repeating

clockwatch with Westminster

chimes, grande and petite son-

nerie, split seconds chronograph,

registers for 60-minutes and

12-hours, perpetual calendar

accurate to the year 2100, moon-

phases, equation of time, dual

power reserve for striking and

going trains, mean and sidereal

time, central alarm, indications

for times of sunrise/sunset and

a celestial chart for the night

time sky of New York City at

40 degrees 41.0 minutes North

latitude.”

The latter is clearly visible in

the accompanying illustrations

along with glimpses of the orig-

inal fitted tulipwood box, inlaid

with ebony and centred by a

mother-of-pearl panel engraved

with the arms of Henry Graves

Jr. and accompanied by the Patek

Philippe Certificate of Origin.

Graves died in 1953, but the

“Supercomplication” remained

in his family until 1969, when it

was sold to SethAtwood, founder

of the Time Museum. Thirty

years later, when Sotheby’s New

York sold “Masterpieces from

the Time Museum,” it made

$11,002,500—as noted above.

Sadly, I have not been able

to ascertain its present where-

abouts, though one British news-

paper, the

Daily Express

, help-

fully noted that it went to a man

in a red tie!

*

You can find the

New York

Times

story and more back-

ground on line at (www.nytimes. com/2014/11/17/arts/design/ saud-bin-mohammed-al-thani- art-collector-for-qatar-is-dead.html?_r=0) and

(http://news.

artnet.com/art-world/sheikh- al-thanis-watch-sells-for-24- million-after-his-mysterious- death-164641).The “Henry Graves Supercompli-

cation,” sold for just over $24 mil-

lion by Sotheby’s Geneva.

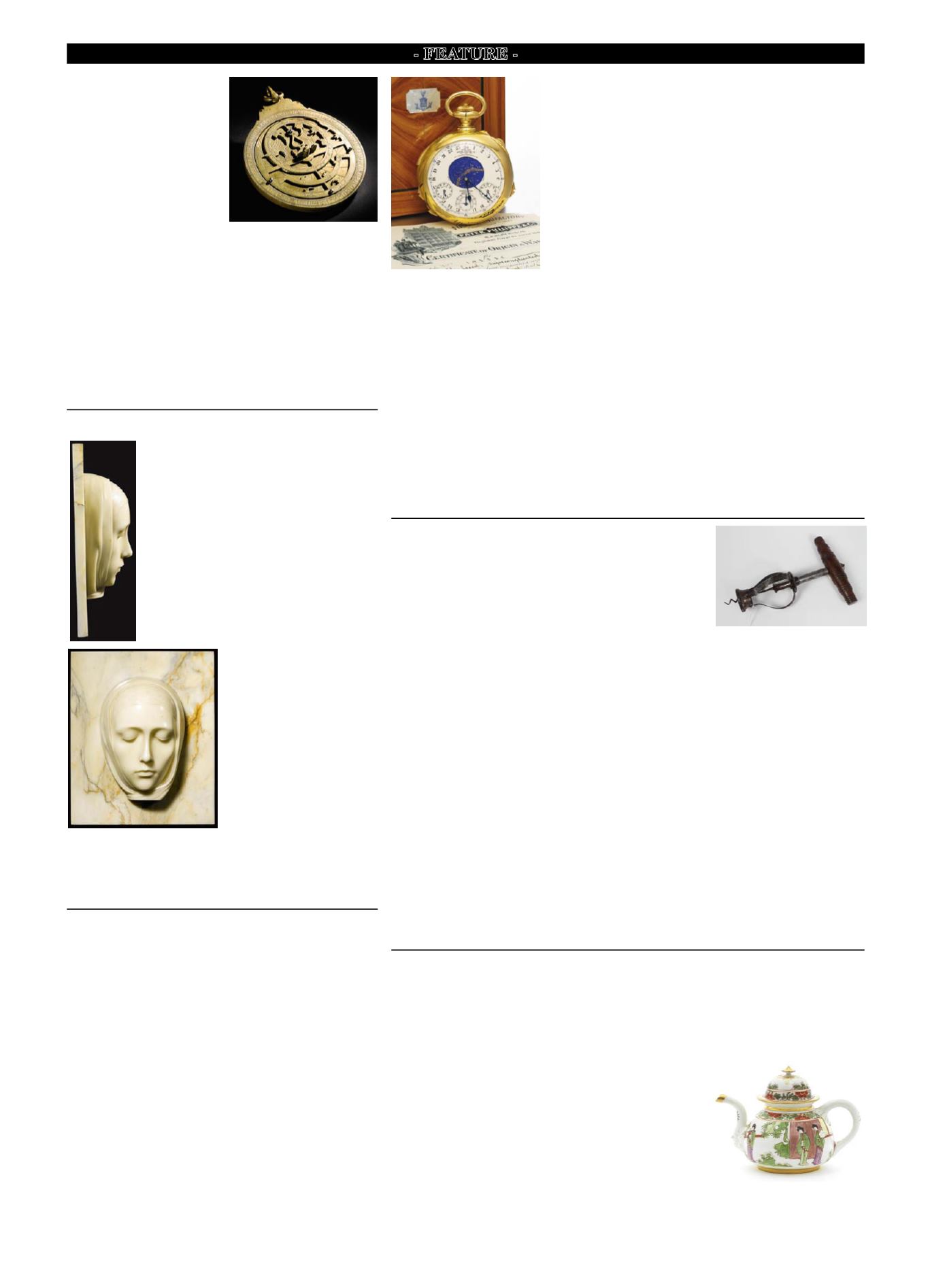

I

t doesn’t work anymore—the

ratchet no longer engages

with the springs—but the pat-

ent corkscrew pictured here is a

real corker and in a November

26, 2014, regional sale, held by

Reeman Dansie of Colchester in

Essex, it was valued at $600/900

but went on to extract a bid from

one admirer of no less $75,540!

Among those who know their

corkscrews, this is perhaps the

ultimate

prize—historically

significant and until last year,

known only from one other

example in an English private

collection.

The standard reference work,

British Corkscrew Patents from

1795

by Fletcher Wallis, iden-

tifies it as just the third British

corkscrew to be patented—

on July 2, 1839, by Charles

Osborne of Birmingham, who

explained the mechanism thus:

“My improvements in the con-

struction of cork-screws consist

in the adaptation or application

of springs. Introducing the worm

into the cork compresses the

bow springs and brings them in

a state of tension. When the elas-

tic force of the springs exceeds

that of the friction between the

cork and the bottle, it will cause

the cork to be drawn up a short

distance, when it can be easily

drawn out in the ordinary way.”

Sadly, Osborne, never lived

to see whether his corkscrew

would be a success, for he died

of consumption only six months

later, but his tragic end certainly

ensured the model’s rarity and

this was a chance that the serious

helixophiles (corkscrew collec-

tors—named for the coiled shape

of the worm) could not afford to

miss.

Almost exactly the same as

the version illustrated in

British

Corkscrew Patents…

, it bears no

actual patent markings but has

the same inscription engraved

to one of the springs: “Made

from the Iron Shoe that was

taken from a pillar that was 656

years in the Foundation of Old

London Bridge.” That medieval

bridge had been dismantled in

1831, following the completion

of John Rennie’s stone arched

bridge—the one that in 1967

was itself dismantled, sold, and

re-erected at Lake Havasu City,

Arizona.

By a remarkable coincidence,

another very early corkscrew had

got collectors excited only a few

weeks earlier, when it turned up

on the French version of eBay.

Utilising bowed springs but

not the ratchet mechanism, that

one was marked to the collar

“Soho Patent” and “By Her

Majesty’s Royal Letters.” My

colleague Roland Arkell, whose

article in an issue of

Antiques

Trade Gazette

first alerted me to

this corkscrew story, noted that

this inscription suggested that

it had emerged from the Soho

(Birmingham) manufactory of

the entrepreneur Matthew Boul-

ton, and that corkscrews made

by Boulton to a 1795 design by

Samuel Henshall are similarly

marked.

Bids on that eBay corkscrew

closed on November 14 at

$27,935.

Happy Days for Helixophiles

Charles Osborne’s record-break-

ing patent corkscrew of 1839, sold

for $75,540 by Reeman Dansie last

November and destined by its new

European owner for his private

corkscrew museum.

L

ast year, the two rare ceramic

pieces illustrated here were

surrendered or, if you pre-

fer, restored into the hands of

descendants of their original

owners when it was recognised

by museum administrators that

they were yet more examples

of those many works of art that

were confiscated from their

rightful owners by the Nazis—

either by straightforward theft or

by forced sales, which amounted

to pretty much the same thing.

The 1998 Washington Prin-

ciples directive, in which 44

nations agreed to take active

steps to return such confiscated

items to their lawful owners

or heirs, sought to address this

issue, but there were all sorts of

problems to face. Many things

had later passed into museums

or private collections across

Europe and around the world,

acquired in good faith without

their new owners having any

notion that they were effectively

stolen goods.

Tracing items that had been

catalogued, formed part of an

inventory, or been otherwise

documented was one thing, but

for many of those seeking to

recover their family inheritance,

things have often proved much

more difficult.

The Meissen teapot and cover

of 1725-30 provides an example

of the well-documented variety.

It was once part of a collection

formed over some 30 years by

the banker Gustav von Klem-

perer and his wife, Charlotte.

Harlequin and the Teapot: Not Restored—Just Restituted

Gustav died in 1926, just as

Ludwig Schnorr von Carols-

feld’s catalogue of what was

reckoned to be one of the finer

Meissen collections of modern

times was published in an edi-

tion of just 150 copies, and that

A Meissen teapot, once part of

the magnificent von Klemperer

collection, sold for $202,230 in

Knightsbridge.

☞