22-D Maine Antique Digest, April 2017

-

SHOW -

22-D

New York City

The New York Ceramics & Glass Fair

by Lita Solis-Cohen

T

he opening moments of the five-day New York

Ceramics & Glass Fair on the fourth and fifth floors

of the Bohemian National Hall at 321 East 73rd

Street in NewYork City on Wednesday afternoon, January

18, were as competitive as at an auction. The major

collectors and curators who had received e-mails with

images of some of the treasures on offer made a beeline

for their favorite stands, hoping their competition hadn’t

gotten there first.

By the end of the three-and-a-half-hour preview,

London dealer Garry Atkins had sprinkled red “sold” dots

in all his cases. New York City dealer Alan Kaplan, who

had a selection of early English salt-glazed and creamware

ceramics from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Henry

Weldon (the things they bought after they gave to Colonial

Williamsburg all the pieces illustrated in the two books

published on their collection), sold quickly to collectors

and to museums.

North Adams, Massachusetts, dealer Leslie Ferrin,

who has been showing contemporary ceramics at this fair

since its earliest days, said the preview gives artists and

collectors a deadline. “Artists need to send their best work

in time for this show, and collectors rush to in to see it, not

knowing who they might be competing against,” she said.

That is why there is excitement in the opening moments

of the ceramics and glass fair, the last of the specialized,

narrowly focused fairs to survive.

Like the London Ceramics Fair, launched by Anna and

Brian Haughton in London in 1981 and which continued

until its demise in 2009, the New York Ceramics & Glass

Fair offers a series of free lectures every day. Generally

well attended by scholars and collectors, it is where

discussions about the latest research, the latest finds, and

the next exhibitions take place and where a limited number

of advance copies of

Ceramics in America

were for sale.

Ferrin led a lively round-table discussion on “What do you

do when the children don’t want it.” The conclusion: this

is a good time to collect because so much is coming on the

market at the same time in a generational shift.

The ceramics and glass fair was smaller this year, with

just 28 dealers. More than half of the exhibitors offered

17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century wares; the rest offered

contemporary studio ceramics and glass. Museum curators

from across the country come to this show, and they set in

motion acquisitions for the year. The 33 museum curators

who shopped at the fair, according to a post-sale press

release, bought antique and contemporary works and put

works on reserve that must be approved by acquisition

committees.

This fair is still weighted toward the old, but it would

not survive without the contemporary. The two galleries

offering the work of several contemporary craftsmen

sold more than the eight craftsmen who represented

This fair is still weighted toward

the old, but it would not survive

without the contemporary.

themselves. There is generally a turnover of individual

craftsmen that keeps the show fresh. The exceptions

were ceramic artists Cliff Lee of Stevens, New Jersey,

the Taiwanese neurosurgeon turned potter who has been

prominent in the crafts world since his inclusion in the

White House Collection of American Crafts in 1993, and

Hideaki Miyamura, the Japanese-born American potter

who works in Kensington, New Hampshire. His work,

like Lee’s, is in major museum collections. Boston artist

Katherine Houston, who makes porcelain still lifes of

fruits, vegetables, and flowers, is a regular at this show and

has a following. Museums have also acquired her work.

The dealers in earlier wares were busy. For some, such

as Alan Kaplan of Leo Kaplan Ltd., New York City, this

is the only show he does (he has a gallery on the sixth

floor of a building on 57th Street where he carries on

business). Garry Atkins comes to New York City from

London just once each year and saves his rarest early

earthenware, delft, and creamware for this fair. Martyn

Edgell of Cambridgeshire, England brings a large stock

of mostly British ceramics from the 17th though the early

19th century. He came to the U.S. twice this season and

showed at the Delaware Antiques Show in November

because his major clients are Americans. Martine Boston

of Limerick, Ireland brought Victorian majolica to the fair.

Her husband, Nicholas, who used to exhibit at the fair, said

he is working on a major museum majolica exhibition to

open in the U.S. in 2018 and is still a partner in yearly

majolica auctions in the U.S.

English ceramics are the strong suit at this fair. Robert

Prescott Walker of Waccabuc, New York, who has been

exhibiting for the past three years under the name Polka

Dot Antiques, said he had his best fair so far. “Historical

Deerfield purchased two of my rarest items—a triple-

colored transfer-printed salt-glazed stoneware plate, 1756-

60, one of only five known to exist—but more importantly

they bought the unique hand-drawn estate plan of Thomas

Whieldon’s estate, dated 1794. It was discovered a few

months ago in the U.K. at an auction of a solicitor’s office

that closed.” Walker said he could have sold it to several

other museums, but Deerfield got there first. He also sold

lead-glazed “Landskip” ware, salt-glazed agate animals,

early English delftware, and Moorcroft pottery.

Baltimore dealers Marcia Moylan and Jacqueline

Smelkinson, specialists in Japan pattern English porcelain

and Georgian and Victorian jewelry, moved their stand

upstairs this year and loved their new location on the

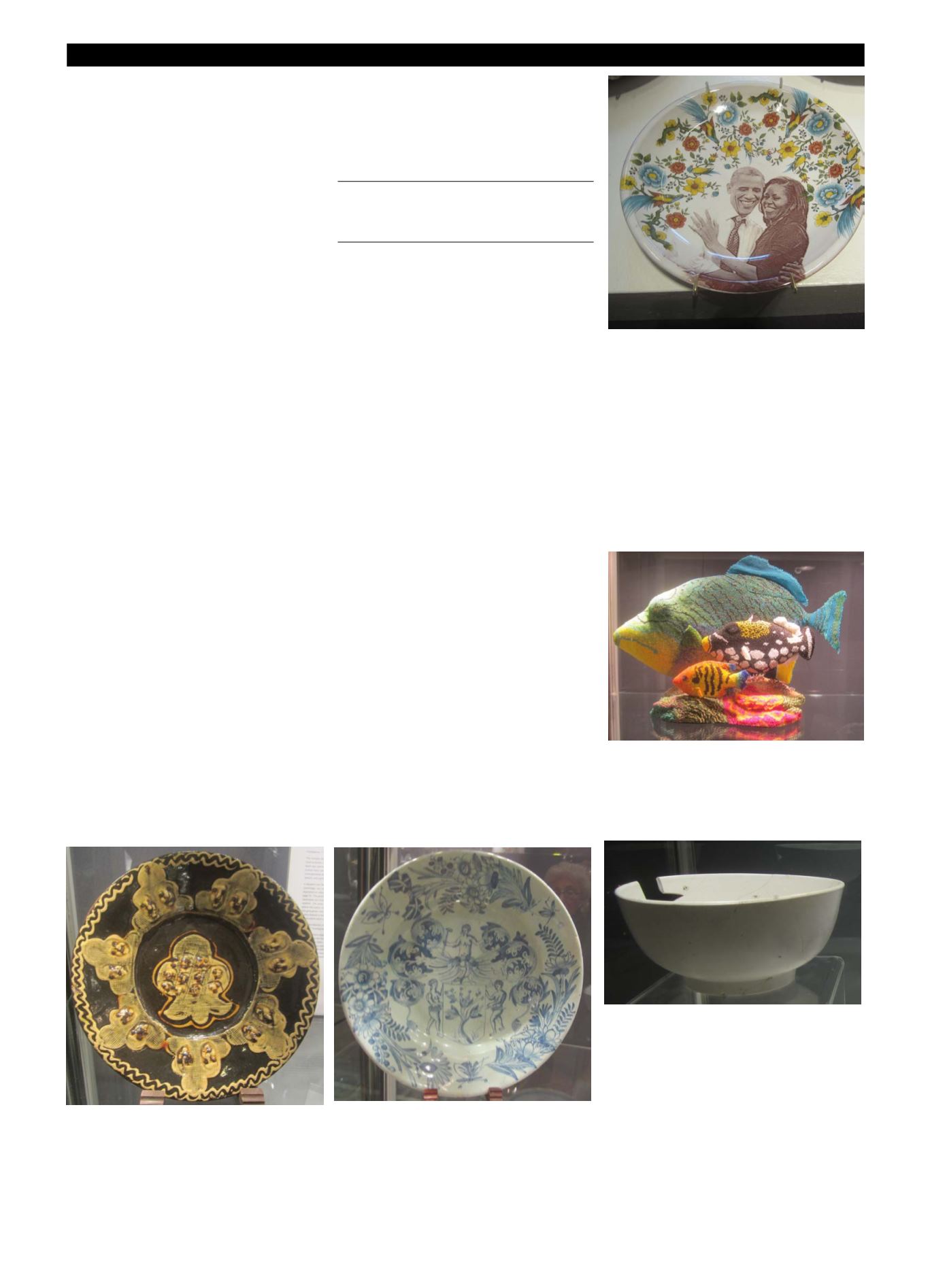

Early in the show, London dealer Garry Atkins sold this

unusual 11" diameter English Staffordshire slipware

dish attributed to Thomas Toft, circa 1675, the rim

with radiating oak leaves with human faces and with a

stylized leaf in the center with more human faces. The

decoration is thought to be symbolic of Charles II hiding

in the Boscobel oak, and the buff clay was given a coating

of black slip before the leaves with human faces were

applied. A similar plate in the Fitzwilliam Museum in

Cambridge, England is signed Thomas Toft.

The 12½" diameter London delftware plate with the arms

of the Tobacco Pipe Makers’ Company, 1670-90, is painted

in tones of blue on a pale blue ground. A tobacco plant is

depicted on a shield supported by a pair of blackamoors;

the crest is a blackamoor holding a clay pipe. It was sold by

Garry Atkins of London.

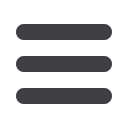

Leslie Grigsby, curator of ceramics and glass at the

Winterthur Museum, makes beaded sculpture. This teapot

of wood, glass, wooden beads, and thread, 11½" x 15" x

8½", is from her water and fish “Water Ways” series. Some

of her sculptures were available for purchase, priced from

$1000 to $12,000. She sold four.

Part of the loan exhibition, this hard-paste porcelain bowl

was probably made at the Bonnin and Morris porcelain

works in Philadelphia, circa 1772. Measuring just 5½"

diameter, it was among the 85,000 artifacts recovered from

the site of the new Museum of the American Revolution

that is to open in Philadelphia in April. Discovered in 2014

and first analyzed by Dr. J. Victor Owen, an expert on the

geochemistry of archaeological ceramics and glass, and his

colleagues, the bowl was identified as being true porcelain,

most likely manufactured in Philadelphia in the 18th century.

Archaeologist and ceramic historian Robert Hunter

believes that the bowl is made of aluminous-silica paste and

reflects experiments with Cherokee clay (kaolin) sent to

Bonnin and Morris in 1771 by Henry Laurens of Charleston,

South Carolina. The findings of Dr. Owens and his colleagues,

along with an article by Robert Hunter and Juliette

Gerhardt, are presented in the 2016 volume of

Ceramics in

America

, published by the Chipstone Foundation.

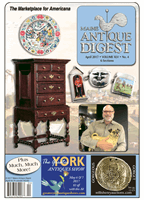

During the election season, Ferrin Contemporary, North

Adams, Massachusetts, showed Justin Rothshank’s

Dinner with the Presidents

and

Know Justice

, handmade

commemorative tableware with transfer prints of

presidents and justices of the Supreme Court, as a way

of creating dialogue about politics. At the Ceramics &

Glass Fair, Ferrin offered Rothshank’s plates and mugs

with the Obamas and with Supreme Court Justice Ruth

Bader Ginsburg for $60 and $70 each. Rothshank works

in Goshen, Indiana. Individual settings and complete sets

are available for purchase and for special exhibitions at

historical societies and museums.

Ferrin said she sold every Rothshank piece she had, but

she did not show his Trump plates because of the protests in

New York City and Washington, D.C., during the fair, even

though the artist said if Ferrin had sold any Trump plates,

he would donate all proceeds to Planned Parenthood.