30-B Maine Antique Digest, April 2017

-

AUCTION -

30-B

Draft of a letter to an unnamed recipient, possibly

Jeremiah Wadsworth, regarding the presidential

election of 1796, two pages on a single 13" x 8" sheet,

New York, early November 1796, one paragraph of

seven lines scored through with ink, some light stains,

a few short marginal repairs, mounting stub at left

margin. It sold for $56,250 (est. $25,000/35,000) to Seth

Kaller, who said it was the most important political

letter in the sale and now is part of his Hamilton

collection that he will offer at the New York Antiquarian

Book Fair at the Park Avenue Armory for $3.5 million

(for the entire collection).

In the 19th century some of the text in this letter was

expunged from the record in

The Papers of Alexander

Hamilton

. The missing comments were highly critical of

Jefferson. The complete text had not been seen for well

over a century by historians.

The rancor between Treasury Secretary Hamilton

and Secretary of State Jefferson as well as the growing

rivalry of the Federalists and the Democratic-

Republicans had induced Washington to stay on for

a second term. His refusal to serve a third term led to

the first contested presidential election in American

history. Federalist Alexander Hamilton supported a

strong central government and backed John Adams and

Thomas Pinckney of South Carolina for vice president.

The Democratic–Republicans favored states rights and

chose Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr of New York.

At the time, electors cast one vote for president

and one for vice president, and the candidate with

the most votes became president and the runner-up

became vice president. Hamilton wrote, “All personal

and partial considerations must be discarded, and

everything must give way to the great object of

excluding Jefferson.” According to the catalog, on

November 8, 1796, Hamilton sent a brief letter to

Jeremiah Wadsworth stating, “A few days since I

wrote you my opinion concerning the good policy of

supporting faithfully

Pinckney

as well as

Adams

,” so

it seems likely that this draft was for a letter

sent to Wadsworth, a Hartford, Connecticut,

merchant and politician who represented his

state in both the Continental Congress and

the United States House of Representatives.

Hamilton was telling him to vote for Pinckney

so that Jefferson would not be elected.

Hamilton’s maneuvering misfired because

winning as vice president positioned Jefferson

to win the presidency in 1800.

Letter signed by Richard Folwell, “Ricd. Folwell,” to Edward

Jones, providing background information, intended for

Alexander Hamilton, on Maria Reynolds and a supposed

conspiracy to entrap him, three pages, 16" x 10", Philadelphia,

August 12, 1797. Reinforced at the central fold and with a few

short marginal tears, it sold for $56,250 (est. $40,000/60,000).

This is one of the few surviving primary documents relating

to the great scandal of Hamilton’s life. It fully corroborates

Hamilton’s explanation of the origin of the episode. Folwell

writes that Maria Reynolds’s husband said she should

insinuate “herself on certain high and influential Characters,—

endeavour to make Assignations with them, and actually

prostitute herself to gull Money from them.”

According to the catalog, in the summer of 1791 23-year-old

Maria Reynolds called on Hamilton, as a fellow New Yorker,

asking him to help her relocate to Philadelphia. Hamilton’s

family was in Albany with his wife’s parents. Hamilton later

wrote in the “Reynolds Pamphlet” that something “other than

pecuniary consolation would be acceptable” to Mrs. Reynolds.

So the young woman became his mistress. In December her

husband, James Reynolds, wrote to Hamilton and said he knew

about the affair and proposed that Hamilton pay him $1000 to

leave Philadelphia. Hamilton paid the blackmail and continued

the affair. Hamilton continued to pay Reynolds other sums.

Later, when Reynolds was imprisoned for forgery, Hamilton

would not come to his aid. Subsequently, Reynolds met James

Monroe, Hamilton’s political enemy, and Monroe made copies

of the Reynolds/Hamilton correspondence and shared it with

Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton continued to attack Jefferson’s

policies and personal conduct. The affair came to public notice

in two pamphlets by James Callendar. Facing ruin, Hamilton

reasoned that he had to issue a pamphlet, in which he fully

admitted to the affair with Maria Reynolds but disproved a

charge of financial impropriety. The Folwell letter reveals the

character of Maria Reynolds and the financial fraud of her

husband and was used by those who rallied to Hamilton’s

support. The Hamiltons’ marriage survived the Reynolds

affair, and while his public life continued, the scandal ended

any possibility of Hamilton’s winning an elective office.

This is a letter by Pierre Charles L’Enfant to Alexander

Hamilton in which L’Enfant seeks Hamilton’s intervention

with the Common Council of the City of New York. It is eight

pages (10" x 7

⅞

"), dated July 14, 1801. The address is at the

foot of the last page, “general Alexander Hamilton”; pages

are numbered [1]–2–7[8], with an integral blank from the

now-lost address leaf bearing endorsements by Hamilton,

including “Compensation to Supervisors Bank of New

York.” With some very light browning, it sold for $25,000

(est. $10,000/15,000). The catalog states, “L’Enfant, who

had served during the American Revolution as a French

volunteer in the Corps of Engineers, redesigned the old

Jacobean City Hall on Wall Street into Federal Hall,

the first capitol of the United States government

under the Constitution. The Common Council of the

City of New York proposed giving L’Enfant ten acres

of land in the city as payment; he refused the tract

as inadequate. In 1801, he again sought payment and

the Council proposed a stipend of $750 for his services.

L’Enfant, on the other hand, sought a fee of $6000,

which he reckoned was the value of the tract of land that

he had originally been offered. In this lengthy letter—

known to the editor of the Hamilton

Papers

only through

a reference to it in Hamilton’s response—L’Enfant

wheedles and coaxes Hamilton to mediate a resolution.”

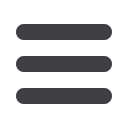

Among the 18 bidders at the

Hamilton sale who had never bid

at Sotheby’s before was Zack

Pelosky, who is in the in fifth grade

at Friends Seminary in New York

City. He came to the sale with his

mother to spend money he had

saved but was not successful. He

tried to buy a manuscript copy

of letters by George Washington

and George Cabot to Timothy

Pickering regarding who would be

second in command of the army

during the Quasi-War with France

in 1798. The lot sold for $1875 (est.

$2000/3000). Zack Pelosky said

he has seen the musical

Hamilton

three times and has a passion for

Hamilton, “not just the musical

but the man and for the American

Revolution.” Solis-Cohen photo.

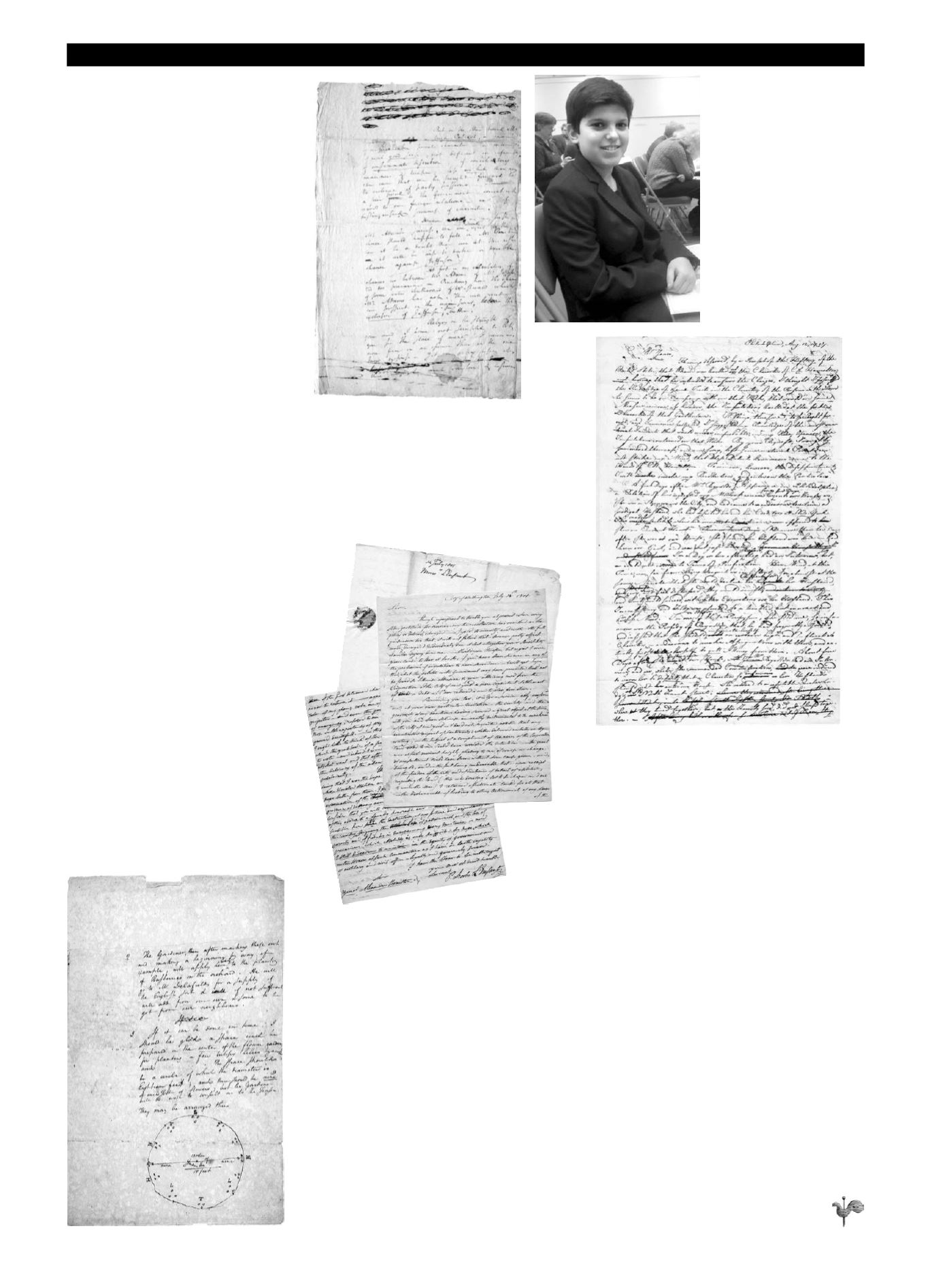

Two autograph memoranda (one shown), one with a

diagram, planning the gardens at the Grange, New

York City, 1802. The first is two pages on a bifolium

(12

⅝

" x 7

⅞

"); the second is 5¾" x 5½". These are

Hamilton’s plans for the gardens for his beloved

Grange, the only house he ever owned. The catalog

states, “The Grange was a handsome two-story Federal

house designed by architect John McComb Jr. and

named after Hamilton’s family house in Scotland, as

well as his uncle James Lytton’s plantation in St. Croix.

The house was originally the centerpiece of Hamilton’s

extensive estate in upper Manhattan. The Grange was

completed in 1802, so Hamilton was able to live there

for just two years prior to his death. The larger of the

two memoranda focuses on flower gardens.”

The letter requests raspberries in the orchard, with

tulips, lilies, and hyacinths in the garden, with wild

roses around the outside and laurel at the foot. The

letter also said, “a few dogwood trees...along the

margin of the grove would be very pleasant, but the

fruit trees there must first be removed and advanced

in front.” The property was designated a National

Historic Landmark in 1960. The Grange has been

moved twice and is now a National Park Service site in

St. Nicholas Park in Harlem. These garden plans sold

for $40,000 (est. $15,000/25,000) to an absentee bidder.