12-B Maine Antique Digest, December 2016

-

FEATURE -

12-B

A

t the landing of the stairwell on the second floor

of the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio, past

three brightly colored kites that seem to lead

the way, visitors step into

An Ohio Childhood: 200

Years of Growing Up

. Curators Andrew Richmond and

Hollie Davis, known to

Maine Antique Digest

readers

for “The Young Collector” column, have put together an

interesting assortment of objects designed to reflect the

life of kids from the early 1800s to today.

It’s befitting that the first few displays include a

juxtaposition of family photos that are as dissimilar as

they are alike. One is a daguerreotype of five children

of John and Persis Follett Parker. The other is a selfie

of Davis and her two children, Nora and Nat. The

19th-century monochrome image is formal and stiff,

depicting stoical faces staring from the plate. Behind it

is the modern self portrait, a large and colorful image of

two smiling children largely obscuring their mother, all

wearing knit stocking caps as they stop for a moment

before heading outdoors to play in the snow. Putting the

two images together, especially with the much larger size

of the vibrant selfie perched behind the daguerreotype,

is like witnessing the scene in

The Wizard of Oz

when

colors rush over the black-and-white film and transform

a make-believe world.

Yet this is an exhibition about fact, not fantasy. For

the curators, putting together that reality came with hard

choices, for how does one condense 200 years of Ohio

childhood into roughly 120 objects? In a way, that task

was made more difficult by the fact that Richmond and

Davis adopted the project after the first curator stepped

aside following a year of planning.

“Initially, Hollie and I weren’t at all involved,”

Richmond said. When the Decorative Arts Center of

Ohio turned to him to finish the exhibit, he did so in

partnership with Davis, who had worked behind the

scenes on two previous exhibitions that Richmond

curated for the house museum,

Equal in Goodness:

Ohio Decorative Arts 1788-1860

and

A Tradition of

Progress: Ohio Decorative Arts 1860-1945

.

While Richmond and Davis had some ideas about

what they wanted to display in

An Ohio Childhood

,

they also inherited material already earmarked by the

previous curator.

“When we took over, there were forty or fifty objects

requested and committed. Some would have been on

our list to choose. Some wouldn’t have been on our

radar,” Richmond said. In other words, some pieces

were a perfect fit for their vision of the exhibition, while

others they made fit.

The biggest challenge, regardless of who did the

picking, was to narrow down the selections to a

manageable number that told the story of children in

the Buckeye State. It was an impossible task, really. It

was also one easily scrutinized through whatever life

experiences (such as economic status) and collecting

preferences (such as toys or textiles) formed the lens of

the viewer.

A variety of objects work together to tell the story of

growing up in Ohio over the past two centuries. “It’s

more than just toys,” Richmond noted. From clothing

to children’s furniture, the options were as deep as they

were wide.

“It was a huge topic, and there was no way we could

do an exhaustive study of that whole subject in the time

and space allotted,” he said. The solution was to come

up with what he described as “a handful of conversations

that each addressed specific issues of childhood in

Ohio.” Those talking points included birth and death,

sickness and health, rich and poor, rural and urban.

In the end, the exhibition drew considerable strength

from two-dimensional objects, especially for its

representation of the 19th and early 20th century.

Paintings and photography are widely used in that

storytelling, but so too are textiles and folk art, from

samplers to fraktur. Throughout the exhibition,

reproductions of vintage black-and-white photographs

serve as a thread to stitch together the storylines being

told. They are a constant—snapshots that capture

various moments of time in children’s lives. There’s one

of a poor farm family posed outside their home, two

young boys in bib overalls, their sister in a ragged dress,

two younger children on their parents’ laps. Another is

a postmortem photo of an infant surrounded by three

siblings who stare blankly at the camera; two adults are

visible holding up a cloth backdrop. There’s a photo of

children outdoors, playing a game of spud. One image

depicts the McIntire Children’s Home baseball team

and another, the Oxford Panthers, an African American

basketball team. One photo shows two child laborers,

boys in the mining industry.

Between these stitches is the life of the exhibit, a fabric

of vintage artifacts that range from folk art portraits,

such as a Charles Soule Jr. (1834-1897) oil painting of

a boy with a dog, to a variety of toys, including an early

Star Wars Millennium Falcon

and corresponding action

figures made by Kenner. Regardless of the object,

whether an 1886 graduation dress, a child’s pressed

glass tea set, or a pair of Art Deco pottery lamp bases

in the form of a dog and cat, each item has a connection

to Ohio.

An Ohio Childhood

doesn’t stop short. It marches

the viewer through a long time line and into the present

with contemporary items, including

Urban Exterior

by

Michael Weisel (b. 1946), a 2014 painting of a father

talking on a cell phone while holding his daughter’s

hand outside a store, and a Little Tikes Cozy Coupe, a

plaything so popular it outsold full-size cars produced

by American auto makers.

The modern side of the exhibition is emphasized

in another way, through the use of technology to help

tell the story. Several iPads are located throughout the

galleries, for use by visitors. Patrons are also encouraged

to download the TaleBlazer app to play an interactive

game, DACO GO.

Additionally, the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio is

hosting children- and family-related programs associated

with the exhibition. For youngsters who might tire of

the displays, there is also a special playroom with a

selection of toys.

One distinct aspect of the exhibit is the gallery guide,

which is actually two booklets in one. For each item

on display, there’s a description written for adults and

one crafted for children.That attention to detail helps set

the show apart, and also establishes why this isn’t just a

hodgepodge of loosely connected artifacts.

Indeed, there is an identity to

An Ohio Childhood

. It’s

part vintage, part selfie, and fully unique.

An Ohio Childhood

remains on view at the Decorative

Arts Center of Ohio, 145 E. Main St. in Lancaster,

through December 31. Admission is free. For more

information, phone (740) 681-1423 or visit (www.

decartsohio.org).

How does one condense

200 years of Ohio childhood

into roughly 120 objects?

An Ohio Childhood: 200 Years of Growing Up

by Don Johnson

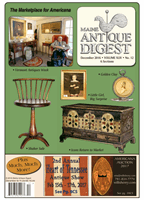

Amodern selfie of co-curator Hollie Davis and her children,

Nora and Nat, is displayed above a daguerreotype of the

Parker children. The two images show the extremes

of photography during the years covered by

An Ohio

Childhood

.

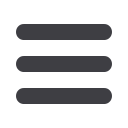

Folk portraits include this oil on canvas of Rhoda Hildreth

with her youngest child, Harriet Eliza, who was born in

1826. Such works were affordable only by the wealthy.

Rhoda’s husband, Dr. Samuel P. Hildreth, was a physician

and scientist.

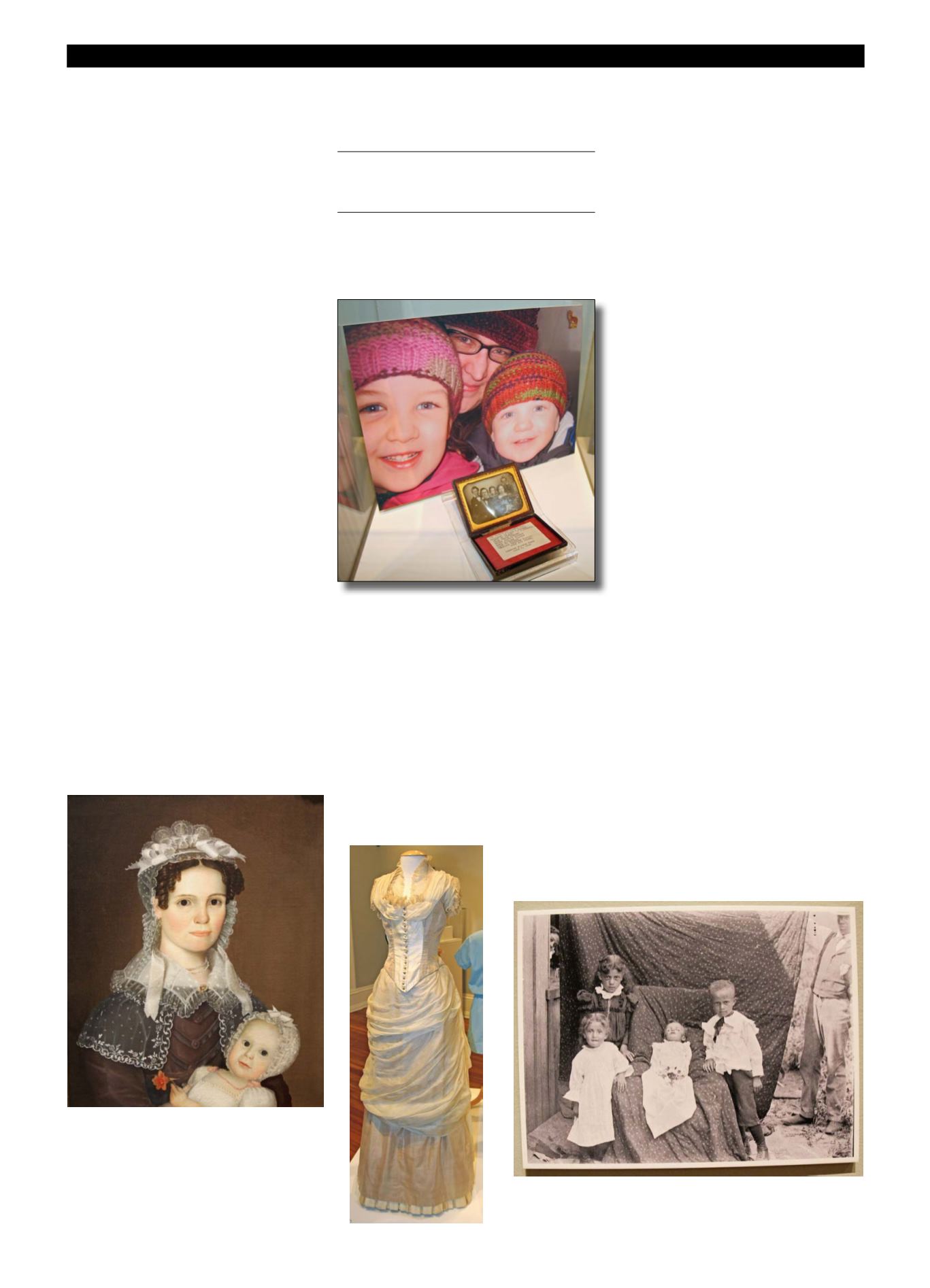

Death isn’t overlooked in

An Ohio Childhood

. Circa 1900, this photo by Albert J.

Ewing (1870-1934) shows a deceased child and three siblings. The gallery guide

notes that “such a photograph might be the only likeness a family had, enabling

them to keep a visual memento of their lost child.”

Worn by Margery Gundry during

her graduation in 1886, this dress was

made by Agnes Quentel, a dressmaker

in Cincinnati.