Maine Antique Digest, December 2016 7-D

-

FEATURE

-

-

London 7-D

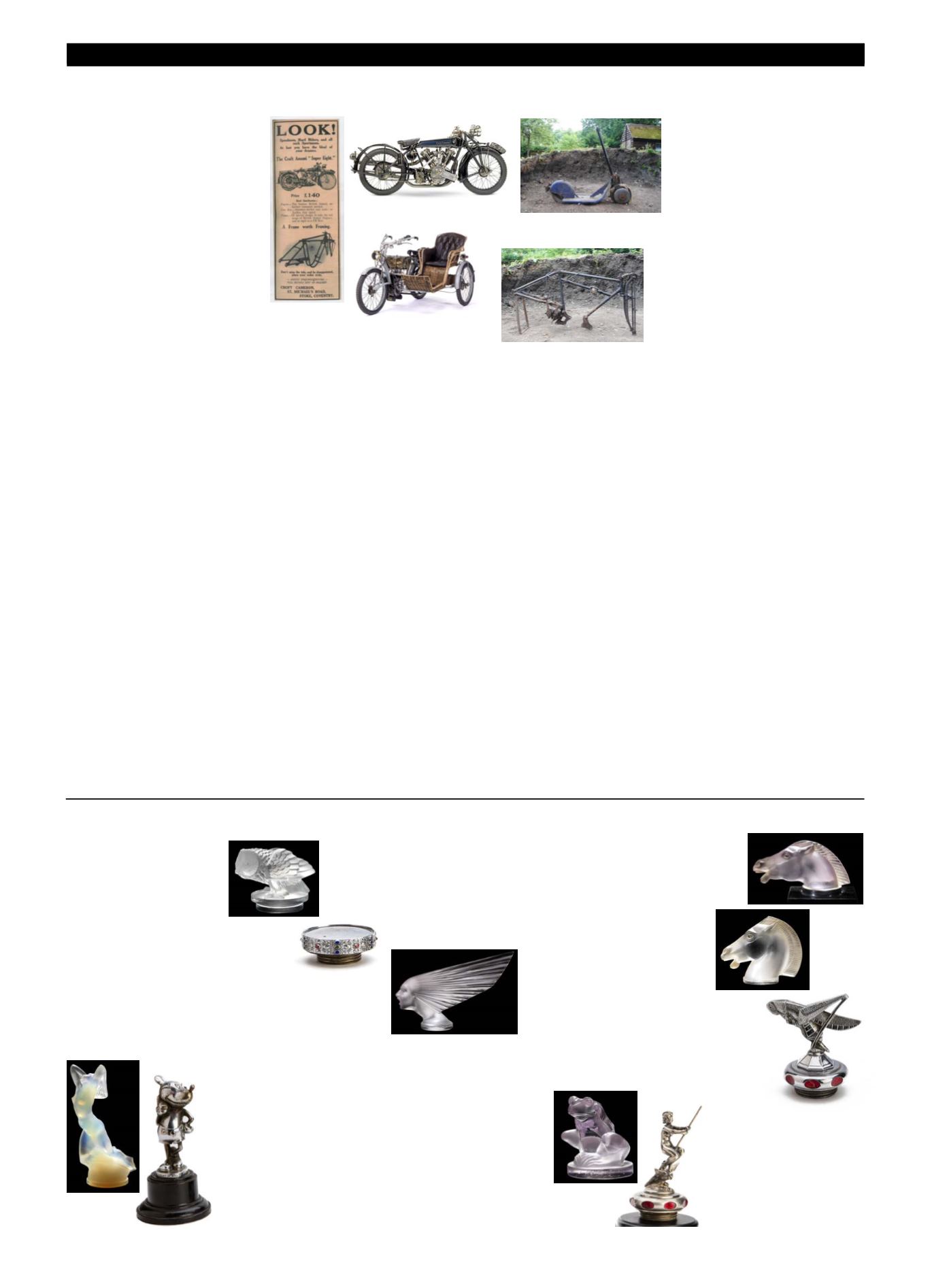

T

he sort of piece that is as

much at home in a decora-

tive arts sale as a car sale, the

blue and white opalescent glass

Vitesse mascot (1) was valued at

around $2500/3500 in the Rob-

ert White sale at Bonhams on

September 19* but sold instead

for $21,190.

A little over 7¼" high, it is

a well-known model that was

launched by Lalique in Septem-

ber 1929, but the best-selling

Lalique mascot in White’s vast

collection, which ran to nearly

300 examples, was the glass

Hibou, or owl, mascot (2) by

Lalique shown above left.

Lalique Creations Lead the Motorised March of the Mascots

I

should make clear at this point that

though I have driven a number of very

different cars in my life, and own an MGB

Roadster that nowadays spends more time

in the garage than on the road, running on

fond memories rather than petrol/gas, I

have only once ridden a motorcycle—and

that under protest and on the pillion seat.

As a young lad, I was for a few years

an Air Training Corps cadet and would

either cycle or travel by train the seven

or eight miles from my Isle of Sheppey

home to the school in the mainland Kent

town of Sittingbourne in which our Fri-

day evening and Sunday morning meet-

ings were held.

Then one Sunday, without a by your

leave, I was told by my mother that our

next-door neighbour, having business in

Sittingbourne that day, had offered me a

lift on his motorcycle.

Now Mr. Ingram was an extremely

rotund fellow, and perching uncomfort-

ably behind him, my arms firmly wrapped

around his bulging, leather-clad body,

as instructed, I was barely able to see a

thing. On a motorcycle of modest engine

size that also seemed too small and fragile

to bear Mr. Ingram’s considerable weight,

let alone my extra burden, I endured a

journey that I swore never to repeat. On

arrival, I made some excuse about the

uncertainty surrounding the time of my

return, and caught the train home instead.

I had an uncle who rode big, power-

ful motorcycles well into old age and

still have one or two friends locally who

ride impressive machines, but for me the

motorcycle romance of the road never

began.

Having made that admission, I move on

now to an October 16 Bonhams motorcy-

cle sale held at the Staffordshire County

Showground to coincide with the Car-

ole Nash Classic Motorcycle Mechanics

Show.

Seen top center is a 1924 Croft Cam-

eron, 986 cc “Super Eight” which in the

contemporary flyer reproduced next to it

cries out, “Look! Speedmen, Hard Rid-

ers, and all such Sportsmen. At last you

have the Ideal of your dreams. The Croft

Anzani ‘Super Eight.’”

Very little is known about the short-

lived, Coventry-based Croft Cameron

The German made Vindec

Special and sidecar of 1907

sold for $39,230.

The Long Island, New York,

Autoped scooter of circa 1919

sold for $2520.

This 1924 Croft Cameron, 996 cc

“Super Eight” sold for $247,455.

A contempo-

rary advertise-

ment for the

Croft Cameron

motorcycle.

This unidentified, but possibly vintage,

motorcycle frame sold for $395.

Two Wheels, Three Wheels and No Wheels

company, which was in business for only

a few years, 1923 to 1926. Aiming at the

very top of the market, the motorcycle

advertised was effectively the only model

(with detail variations) that the company

ever produced.

It was available in eight-valve form at

£140 (today about $170), or four-valve

at £125—and there was also the option

of a slightly larger “Plus Power” Anzani

engine at a very modest premium.

For reasons that I am sure are already

apparent, I will let the Bonhams cata-

loguer take over here: “Its magnificent

power unit aside, one of the Croft Cam-

eron’s most striking features was its

advanced duplex loop frame that com-

pletely encircled the engine. Its manu-

facturer claimed that this frame was ‘as

rigid as a Pill Box,’* while

Motor Cycling

reckoned it made ‘for great lateral rigidity

and, consequently, for good steering.’

“The leaf-sprung front fork was by

Montgomery, and contemporary photo-

graphs of the Croft Cameron show that

it was built with various combinations of

dummy belt rim and drum brakes, even-

tually ending up with the latter at both

ends, as seen here. A (probably optimis-

tic) weight of 300 lbs was claimed.”

Bonhams go on to observe that the

“Super Eight” was undeniably hand-

some and a worthy rival for the Brough

Superior, which it matched on price—but

the reasons why Croft Cameron failed

while Brough prospered will, probably,

never be known.

Purchased new in 1924 by a Mr. Bert

Henson, a railway engine driver, who

later added a sidecar, this one was retired

in 1956 but purchased only a year later by

the consignor’s father. Restored in 1962,

it has been a regular entrant in Vintage

Motor Cycle Club events but was last run

around five years ago.

Among the 150 or more motorcycles

offered by Bonhams, from vintage to rel-

atively modern, this was easily the most

expensive of them at $247,455.

I should point out that even I have

heard of the abovementioned and leg-

endary Brough Superior** the motor-

cycle on which Lawrence of Arabia met

his untimely end. The Bonhams sale did

include one of those, an ex-police machine

with sidecar (the body a replacement) that

sold for $104,170, but as a motorcycle

and sidecar combination I have selected

instead something a little earlier and, to

quote Bonhams, “ultra-rare.”

Pictured bottom center is a Ger-

man-made Vindec Special of 1907 with a

5 hp Peugeot v-twin engine that sold for

$39,230.

In 2007, to mark the event’s centenary,

its owner rode it in solo form in a re-

enactment of the very first running of

what became one of the great motorcycle

race meetings of all time, the Isle of Man

TT. In that inaugural 1907 race another

Vindec Special, ridden by “Billy” Wells,

had taken second place.

The Bonhams machine is seen with the

wickerwork sidecar by Graham Brothers

of London that was fitted in 1908 or ’09.

Both motorcycle and sidecar were redis-

covered and restored in the 1960s.

Moving from beautifully restored

machines to “projects,” I have chosen two

more lots from the Stafford sale.

Illustrated top right is a 162 cc Autoped

scooter of circa 1919. Billed as one of

the very first attempts to build a via-

ble motor scooter, it was manufactured

by the Autoped Corporation of Long

Island, New York. It was first marketed

in 1916 at $110—toolbox, lights, and

horn available at extra cost—and its

handlebar stem could be folded down

and attached to the rear mudguard to

form a carrying handle. As such, it was

presumably intended as a means of

countering congestion in an already

overcrowded metropolis.

American production had ceased by

1920, but an improved version, one that

incorporated a seat, was produced by

Krupp in Germany in the following year.

This basic U.S. model was sold at

$2520.

Finally, the bare bones project, or

where do we look now? Catalogued sim-

ply as “an unidentified, believed vintage

motorcycle frame” and bearing the num-

ber 3922, the forlorn-looking lot pictured

bottom right was sold for $395.

*

In this context, I imagine, the term

“Pill Box” refers to the reinforced con-

crete structures, intended to house men

and guns, erected around the country as

part of the U.K.’s defence against possible

invasion.

**

A collection of Brough motorcycles

owned by Robert E. White, whose enor-

mous collection of car mascots is featured

elsewhere in this “Letter,” was sold pri-

vately for $3 million to Jay Leno. See also

the “Robert White’s…Watch” story.

Introduced in January 1931,

this striking avian mascot, mod-

elled in clear and frosted glass, is

5" long overall and though it fell

a little short of estimate, it did

sell at $61,945.

Two equine mascots by

Lalique, both 5" high and dating

from 1929, were also among the

higher-priced lots.

The double-maned example

(3), named Longchamp after the

famous Paris racecourse in the

Bois de Boulogne, was sold for

$14,670, and the other horse’s

head, known as Epsom after the

most famous British racecourse

(4), reached $20,280.

With a pale amethyst tint and

satin finish, the latter has been

mounted as a bookend, which to

some automobilia lovers may be

seen as the mascot equivalent of

being retired and put out to grass.

I rather liked a little Grenouille

or frog mascot (5), a clear and

frosted glass figure with an ame-

thyst tint that stands just 2½"

high. It sold at $8475.

Victoire, a Lalique mascot of

1928 (6) that is 10¼" long over-

all, sold at $27,710—yet another

example of the Lalique mascots

in the Robert White sale that

made considerably more than

predicted—but an example of the

well-known Comète mascot of

1925, valued at $26,000/39,000,

failed to sell.

Other mascots which caught

my eye included a French

chrome-plated bronze Locust

(7) sitting on a radiator cap stud-

ded with what look like little red

cameos that was made in the

1930s and bears an “E.G.” mak-

er’s mark.

It sold at $6195, as did the

Sorceress, or witch, mascot (8)

that has a very similar-looking

base—though in this case those

insets are described as “red

reflectors.” Catalogued as an

Austrian piece by Bergman that

dates from the 1920s, it is signed

“N. Greb” and now sits on a later

display base.

An Isotta-Fraschini Crown of

Lombardy mascot (9), chrome

plated and set with enamel “jew-

els,” that sold for $7825 is said

to be one of only three made for

the Italian car manufacturer’s

show cars at the 1930 London

Motor Show.

My final pick is a chrome-

plated Mickey Mouse mascot

(10) with what were catalogued

as pie-crust eyes. Standing 5½"

tall and marked “Produced by

consent of Walter E. Disney”

around the display base, it sold

for $7335.

*

See also the George Daniels

watch story in this “Letter.”

(2)

(1)

(3)

(4)

(6)

(10)

(8)

(7)

(9)

(5)

(3)