6-D Maine Antique Digest, December 2016

-

FEATURE

-

-

6-D London

Letter from London

by Ian McKay,

<ianmckay1@btinternet.com>

A

rather unusual “Letter” this month. With many of the early

season London sales given over to modern and contemporary

art, I thought it might make a change to tackle something different.

Noting that Bonhams had held quite a lot of car, motorcycle, and

general automobilia sales in recent weeks—in England, Belgium,

and France—I plucked up courage and dipped into an auction world

in which, I here admit, I feel rather more out of my depth than usual.

However, in I dived and got somewhat carried away. I hope that

some of what follows will appeal to some readers, but for those who

are not at all interested in this sort of thing, I offer my apologies and

point out that there are also quite a few words on Brian Sewell’s

picture collection, one of George Daniels’ special “Anniversary”

watches, and a cue stand.

R

enowned British art critic,

journalist and author Brian

Sewell, who died in 2015, was a

man who regularly courted con-

troversy through what some oth-

ers regarded as his unfashionable

views and his forthright dismissal

of art and artists that he despised.

In the distinctive, high-pitched,

plummy and, to some, almost

comically affected voice that

made his pronouncements unmis-

takable, he once called fellow

art critics “a feeble, compliant,

ignorant lot,” and of Britain’s

ever-controversial Turner Prize

for contemporary art, he sug-

gested that “Ignoring it is the

kindest thing one can do.”

Inevitably, Sewell raised hack-

les in the art world, and in the

1980s one group of 36 offended

critics and members of the arts

world signed a letter to the editor

of a national daily, the

Evening

Standard

, demanding that he be

sacked as their art critic.

They accused him of both “vir-

ulent homophobia and misog-

yny” and of being “deeply hostile

to and ignorant about contempo-

rary art.”

Sewell’s response, according to

a recent BBC obituary, was “We

pee on things, we pee into things,

we pee over things and we call it

art. I don’t know what art is, but I

do know what it isn’t.”

It was, however, Sewell’s role

as a collector that was remem-

bered and celebrated in a $4.857

million sale held on Septem-

ber 27 at Christie’s—an auc-

tion that showed the breadth of

his interests, from the works of

16th-century artists of the Italian

Renaissance to those of his near

contemporaries.

Sewell had worked in the

saleroom’s picture department

between 1958 and 1966, and Noël

Annesley, a former deputy chair-

man of Christie’s U.K. who had

once worked as his assistant, pro-

duced an appreciation of Sewell

for the saleroom’s website. Part

of the online catalogue, it was at

the time of writing still accessible

at (www.christies.com/features/ Art-from-the-Collection-of- Brian-Sewell-7611-1.aspx).*That BBC obituary and other

details relating to the career and

life of this controversial and

colourful critic may also be found

online.

The most successful of the

Sewell lots, at a five times esti-

mate $1,033,710, was a large and

highly finished study in black

chalk that relates to Daniele Ric-

ciarelli’s bronze sculpture of a

sleeping

Dido

that is now in the

Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in

Munich.

A painter as well as a sculptor,

Ricciarelli, or Daniele da Volterra

as he was also called, often cast

bronze models in preparation for

his pictures and used drawings of

those casts to explore and plan

his compositions in great detail—

presumably to test which view-

points would best suit the final

painting.

Sewell’s drawing follows the

Munich bronze with precision,

said the cataloguer. “The shad-

ows are indicated with very fine

hatching and the body is mod-

ulated with such fine lines that

they almost dissolve and give the

figure a sculptural quality.”

(The Munich bronze, it should

be noted, had been acquired by

the museum as a work by Adri-

aen de Vries [circa

1556-1626]

and was only correctly identified

as being by Daniele in 1993, by

Professor Paul Joannides.)

This figure seen in the study

offered at Christie’s also appears

in a painting by, or after the art-

ist, called

Aeneas commanded by

Mercury to leave Dido.

The pres-

ent whereabouts of that picture

are unknown but the large num-

ber of studies for the painting that

survive are testimony to the care

that Daniele took in preparing it.

Sewell’s picture may be the only

surviving drawing of Dido, but

there are five extant studies for

the child who assists Aeneas to

disrobe.

It is thought that Sewell’s

drawing once belonged to Filippo

Buonarotti, a descendant of

Michelangelo, and when first

sold by Christie’s in 1860 (for

18 guineas) it was catalogued

as “A Female Figure Reclin-

ing: A Model for the Tomb of

the Medici.” Its true creator was

revealed only after it had arrived

at Christie’s—and as Annesley

remarked in his essay on Sewell,

“…it’s a shame that he was not

able to enjoy its recent identifi-

cation as one of Daniele’s most

beautiful drawings.”

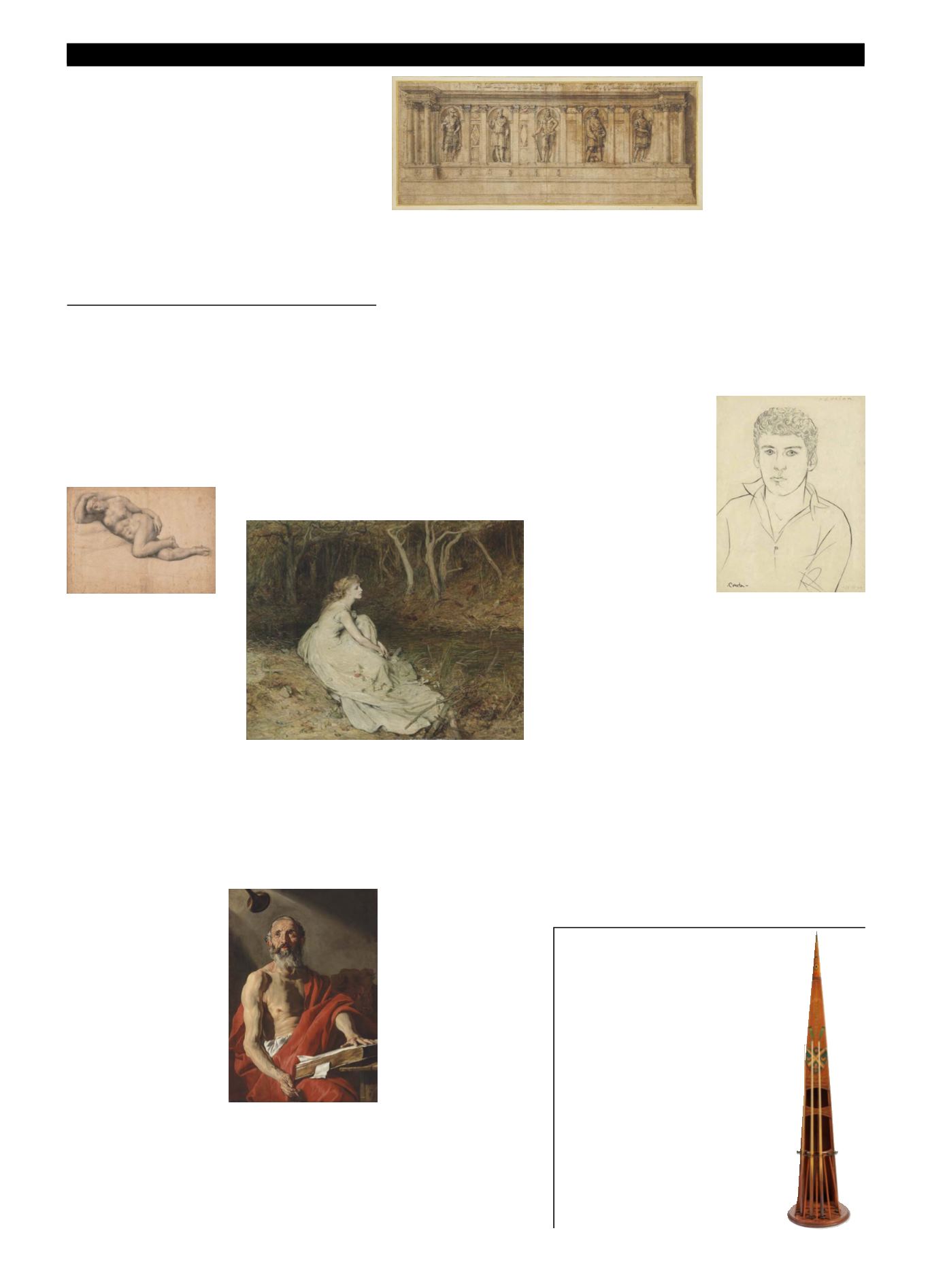

Of three paintings by Matthias

Stomer (c. 1600-after 1652) that

Sewell was particularly proud of,

two failed to sell, but a portrait of

St. Jerome

brought a double esti-

mate $473,405. When purchased

by Sewell at Sotheby’s in 1981,

it was still attributed to Hendrik

van Somer.

Sold for $457,840, a chalk, ink

and wash drawing by Baldassare

Peruzzi (1481-1536) was the ear-

liest work in Sewell’s collection

and another of those works that

he regarded with particular pride

and joy.

It is a design for a bench that

in its five niches contains figures

thought to depict heroes of past

times—though that on the far

left is identified only as “a young

hero” and the fellow on the far

right has been only tentatively

linked with Julius Caesar. The

others are more formally named

as Marcus Atilius Regulus, Her-

cules, and Lucius Junius Brutus.

It was following the 1527 Sack

of Rome by mutinous troops

of the Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V that Peruzzi left Rome

and returned for a few years to his

native Siena.

There he was appointed

“Architetto della Repubblica”

and it was probably in this capac-

ity that he executed this drawing

as a possible feature of the Sala

del Cancelleria, or Chancery

Room, in the city’s planned new

Palazzo Pubblica. The drawing is

inscribed by the artist with alter-

native sets of measurements for

the projected bench, but that par-

ticular project was never realised.

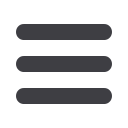

Avery different side to Sewell’s

tastes and collecting is seen in

an oil by Sir William Quiller

Orchardson (1832-1910) featured

among the accompanying illus-

trations. Aportrait of

Ophelia

, the

tragic heroine of Shakespeare’s

Hamlet

, seated on the banks of a

woodland stream, where “a wil-

low grows aslant a brook” and in

which she later drowned, it was

sold at $56,745.

A youthful prodigy who had

entered the Trustees’Academy of

Edinburgh aged just 13, Orchard-

son at first painted mainly literary

scenes, drawing inspiration from

the works of Shakespeare, Scott,

Dickens, and Keats, among oth-

ers, until moving to London in

Daniele Ricciarelli’s study in

black chalk of a sleeping

Dido

sold

for $1,033,710 as part of the Brian

Sewell sale.

A chalk, ink, and wash design by Baldassare Peruzzi for a memorial

bench sold for $457,840.

Matthias Stomer’s portrait of

St.

Jerome

sold at $473,405.

1862. In his later career he turned

his hand to historical subjects,

portraiture and to the “psycho-

logical dramas of upper-class

life” by which he is perhaps best

remembered. An 1883 painting

on the subject of

The Marriage of

Convenience

is a good example

of the latter.

Sewell, as Noël Annesley

noted, may have become famous

for his trenchant reviews of the

British art scene and his denun-

ciation of many contemporary

artists and fawning fellow critics,

but he also found much to admire

in the art of the 20th century.

Harold Gilman, Duncan Grant,

Augustus John (whose two stu-

dio sales Sewell catalogued at

Christie’s), John Minton, and

Walter Sickert were among the

artists whose work appealed to

him, as was John Craxton, whose

pencil drawing of his friend,

Lucian Freud sold at $64,850.

*

A few other works from the

Sewell sale are illustrated in that

online article by Noël Annesley.

They sold as follows: An oil on

canvas study of the

Madonna

& Child with Saints Ignatius of

Loyola, Francis Xavier, Cosmas

and Damian

by Andrea Sacchi

that relates to his ceiling fresco of

circa 1629 in the Old Pharmacy

of the Collegio Romano in Rome

went at $302,200; a squared

black chalk drawing of a soldier

carrying a ladder by Agostino

Ciampelli (1565-1630) sold for

$154,020; a pencil, chalk, and

ink drawing of a seated male

nude by James Barry of Cork

(1741-1806) sold at $113,490;

and a 1959 tempera on board

still life of

Twelve Pheasant Eggs

by Eliot Hodgkin made $61,610.

John Craxton’s pencil drawing of

his friend Lucian Freud sold at

$64,850.

“I Don’t Know What Art Is,

but I Do Know What It Isn’t”

Sir William Quiller Orchardson’s portrait of

Ophelia

sold for $56,745.

Scull and Crossed Oars

O

ffered with an early 20th-century mahogany

scoreboard of fairly standard form, this bil-

liards cue stand is rather more of a novelty. Stand-

ing 8' high, it is formed from the bow of a rowing

scull and decorated with a shield, crossed oars and

a legend that links it to the Cambridge R[owing]

C[lub] and the Henley Royal Regatta of 1896.

Nowadays held over a five-day period in July,

the world famous annual regatta’s origins lie

traditionally in the first Oxford v. Cambridge

university boat race, which was held on a course

from Hambleden to Henley-on-Thames in 1829.

In a Bonhams sale of October 11 that described

itself as “A Royal Collection: The Contents of an

English Country House,” the cue stand and score-

board together sold for $765.