26-A Maine Antique Digest, May 2015

- FEATURE -

R

ight out of law school I

was routinely in court to

appear on some motion

or another—occasionally to try

a small case. Despite the theory,

philosophy, public policy, pub-

lished opinions, moot court, and

all the rest that constitute the law

school experience, the real world

is where young lawyers learn

what it means to be a real lawyer,

and there’s plenty of learning to

be done. I particularly remem-

ber two lessons that were eye

openers.

Smarts

The first is this—all of the

education and testing to the nth

degree notwithstanding, not every

lawyer is a smart guy or gal. Take

class rankings—you know, where

100 students are scaled from first

to last, based upon grade point

average. Well, this means that in

a class of 100, someone is at the

top, someone is at the bottom, and

everyone else is slotted some-

where in between with half fall-

ing below the midpoint. (I under-

stand that class rank, GPA, SAT,

LSAT, etc. are not perfect indica-

tors, but they are widely accepted

as relevant in determining abil-

ity and predicting success.) The

simple truth is that some of the

folks in the legal ranks are not the

brightest bulbs on the Christmas

tree. Soon after I joined the legal

circle, no one had to point this

out to me. It was apparent. Think

about that the next time you’re

overly impressed when someone

is introduced as an attorney.

Make Believe

I had been in practice for a cou-

ple of years before I experienced

the next big awakening. When

you start out, you don’t know

a lot, and it takes a while to get

your feet planted and gain a grasp

of what you’re frequently called

upon to do. During this period,

there’s a tendency to defer tomore

experienced lawyers you see as

being above you, but one day it

happens. You’re dealing with an

attorney who has been in prac-

tice much longer than you when

you suddenly realize—this guy

knows less than I do. Quickly it

becomes clear that you’re already

a better lawyer than this person,

and he or she doesn’t seem to

have much insight, knowledge,

or command for the issue. It’s as

if this person is pretending to be a

real lawyer but isn’t.

My “Wow!” moment came

soon after one of these encoun-

ters. I was reading an article

in a bar journal, and the writer

addressed this very point. A lot

of lawyers spend their careers

pretending to be real lawyers,

he wrote, when their dearth of

knowledge and ability makes

them lawyers only by title and

license. It was a profound dis-

covery that altered how I have

since viewed other lawyers.

Some are topnotch. Most are

fine. Some are neither. It’s good

to know that fact, if you’re going

to be involved with them.

Guess What?

Now, before you start with

the lawyer jokes, here’s another

truth I found while working with

other professionals. These rules

aren’t limited to lawyers. They

apply equally to the others—

accountants, architects, dentists,

educators, engineers, physicians,

airline pilots, psychologists, sea

captains, etc. Half of those in

every segment were below the

midpoint in their classes, which

might say as much about inad-

equate personal characteristics

(e.g., discipline, organization,

focus, precision, and determina-

tion) as it does about intellectual

capacity. Whatever the cause,

many of these practitioners are

not nearly as skilled as the public

would believe or want. If you’re

looking to engage a professional

or other specialist, you had better

remember these rules during the

search and hiring process.

Oh, and...

Did I mention auctioneers?

Well, I should have, because

these rules apply to them as well,

and you don’t have to attend

many auctions to see what I

mean. That’s my big point. You

can’t flip through a list of names

and select just any auctioneer and

expect a consignment to proceed

smoothly and successfully. The

world of chance doesn’t work

that way, and the auction mar-

kets don’t either. Consequently,

every consignor needs to use

scrutiny in selecting an auction-

eer to handle a valuable consign-

ment. That’s a key tenet in this

series on consigning to auction

that we’re in the midst of, with

this month’s installment focus-

ing on selecting an auctioneer.

Looking Back

We’ve already considered a

number of steps in the consign-

ment process. Most recently, we

sawhowan inquiry letter, ormore

formal “Request for Quote,” can

be used to pose questions and

seek proposals from auctioneers

regarding the handling of a con-

signment. The consignor wants

to obtain as much information as

can reasonably be gained from

each candidate contacted. Work-

ing like a gold miner using a pan,

the consignor wants to scoop up

a lot of “material” for sifting

and examination to find the nug-

get—the best auctioneer for the

assignment.

Paring Down

The consignor should compare

and contrast what is obtained

from the different candidates.

Look for points that are both

appealing and not and note them.

Look at the questions asked and

the answers received. Pay atten-

tion to questions that weren’t

responded to, because omission

can reveal points of possible

concern. Look for what doesn’t

add up, doesn’t feel right, and

doesn’t make sense. Never doubt

gut instinct, because a consignor

has this instinct to help spot

problems and avoid the threats.

Once all of the candidates’

responses have been reviewed

and analyzed, the consignor

should be in a position to narrow

the candidates to a few finalists,

maybe two or three auctioneers.

These are the candidates the con-

signor should interview in per-

son or by telephone.

Big Deal

Interviews are a big deal. The

path to almost every big job or

position runs through an inter-

view process.

In legal practice, the initial

interview with a potential client

is critically important to being

offered a case, as well as decid-

ing whether to accept it. It’s the

opportunity for each party to

meet the other, ask questions, get

answers, and measure whether

the fit seems good. The same is

true for a consignor interviewing

an auctioneer candidate.

A consignor needs to be pre-

pared to conduct an interview,

and that means knowing the top-

ics to be covered, asking good

questions, listening closely to

the answers, and following up, as

needed. This is the best chance

for the consignor to engage in

a real-time give-and-take with

an auctioneer, while observing

the auctioneer’s tone, attitude,

demeanor, and level of interest.

There’s a ton of information that

can be gained by a good digger.

Tips

Here are several interview tips.

First, make a comprehensive

checklist of the topics to cover.

This is your best chance to get

all you want from the horse’s

mouth, so don’t be ill-prepared

and overlook something.

Second, relax, talk conversa-

tionally, and ask compact ques-

tions that hit the point. Listen

carefully to the answers—very

carefully. Follow up with addi-

tional questions, until you’ve

gotten a satisfactory answer on

each point.

Third, don’t be timid. You’re

talking about your money. Act

as though it’s important to you,

because it probably is.

Fourth, don’t be apologetic—

either for your questions or the

time the interview takes. The

auctioneer’s business is search-

ing for quality consignors. For

further explanation, reread the

third point.

Fifth, if you encounter a hur-

ried, impatient, indifferent, lacka-

daisical, uninformed, or unpleas-

ant auctioneer—stop! You’ve got

your answer on that candidate.

Finally, of course, you’re

going to ask about the auction-

eer, qualifications, experience,

the auction, other auctions, your

property, bidders, bidding, the

time and place, selling commis-

sion, costs, and so forth. Aside

from all of this usual discussion,

here are five areas that can prove

very insightful.

Marketing

Ask people what the single

most important factor is to the

success of an auction, and the

number who would give the right

answer is about zero. Is it the

auctioneer’s personality? Nope.

How about the bid calling? For-

get it. Maybe it’s the order of the

lots? No way. So what is it?

The answer is the marketing

campaign, which explains why

I regularly mention the immense

role that marketing plays. A con-

signor is well advised to inquire

about every aspect of how the

auctioneer would handle this

function, the costs, the advan-

tage this auctioneer would bring

over others, and the expected

results. The success of the auc-

tion depends squarely upon the

quality of the marketing and

related response.

Money

A consignor consigns to gain

money. This means an auction is

all about money. The consignor

wants to obtain all of the finan-

cial details that will be involved.

An auctioneer’s charges should

be easy to understand and simple

to calculate.

Unfortunately, there are auc-

tioneers who use veils to conceal

costs and convoluted formu-

lae that beg for a computerized

spreadsheet. The consignor

should ask the auctioneer to

work through some examples,

including all fees and costs, to

ensure that the consignor knows

what doing business will cost.

Be certain to ask how the buyer’s

premium will be used. This is the

consignor’s money, so the con-

signor wants to know and agree.

Competitors

Ask the auctioneer who the

top houses are for handling this

type of property. What are the

pros and cons associated with

each? Ask what separates this

auctioneer from these competi-

tors and whether objective data

exist to verify this. Also ask the

pros and cons of using this auc-

tioneer. You can expect to get

some unexpected information.

Other Consignors

Others have walked the path

the consignor is contemplating.

The experiences of some of

these folks can be insightful and

useful. Ask the auctioneer for

recent references with the same

or similar property—not letters,

but people who can speak by

telephone about the experience.

The consignor wants to learn

the details of what happened in

the marketing, auction, and set-

tlement phases, along with the

person’s satisfaction or not. Ask

what drew the person to the auc-

tioneer, whether the auctioneer

performed as promised, what the

person liked and disliked most

about the auctioneer. Did the

person attend the auction and,

if so, what was that like (i.e.,

auctioneer, staff, organization,

crowd, bidding, etc.) and would

the person use the auctioneer

again?

Flexibility

The consignor should set the

table for the contract negotiation

that will follow. There will be a

number of points to negotiate,

so this idea should be put on the

table. Start to grease the process

by asking the auctioneer “How

much flexibility do you have to

revise the consignment contract as

I would need?” Then be quiet and

listen carefully to the answer. If the

reply is little to none, you should

focus on the other candidates.

Conclusion

After conducting these inter-

views and reviewing what you

learned against what you want,

you should be in a position to ten-

tatively select an auctioneer. The

reason for the lack of finality is

that there’s still a consignment

contract to negotiate. Sealing the

deal with the candidate selected

will depend upon getting a con-

tract that will work as wanted.

Next time, we’re going to

examine some of the key con-

tract terms that a consignor will

want to negotiate. Until then,

good bidding.

Steve Proffitt is general counsel

of J.P. King Auction Company,

Inc., Gadsden, Alabama. He is an

auctioneer and instructor at the

Reppert School of Auctioneering

in Auburn, Indiana, and at the

Mendenhall School of Auctioneer-

ing in High Point, North Carolina.

The information in this column

does not represent legal advice

or the formation of an attor-

ney/client relationship. Readers

should seek the advice of their

own attorneys on all legal issues.

Proffitt may be contacted by

e-mail at

<sproffitt@jpking.com>.

Auction Law and Ethics

Prepare to Listen

by Steve Proffitt

Historical blue Staffordshire, Liverpool pitchers,

War of 1812 luster jugs, and snuffboxes of American interest.

One piece or a collection. All letters answered. Instant cash paid.

W. R. Kurau, Jr.

P.O. Box 457, Lampeter, PA 17537

717-464-0731 • e-mail:

lampeter@epix.net✴✴✴

WANTED TO BUY

✴✴✴

APPRAISALS ESTATES BOUGHT

Q

uaboag

V

alley

a

ntiQue

C

enter

10 KNOX STREET, PALMER, MA 01069

(413) 283-3091

www.quaboagantiques.comHOURS 9-5 TUE.-SAT., 12-5 SUN.

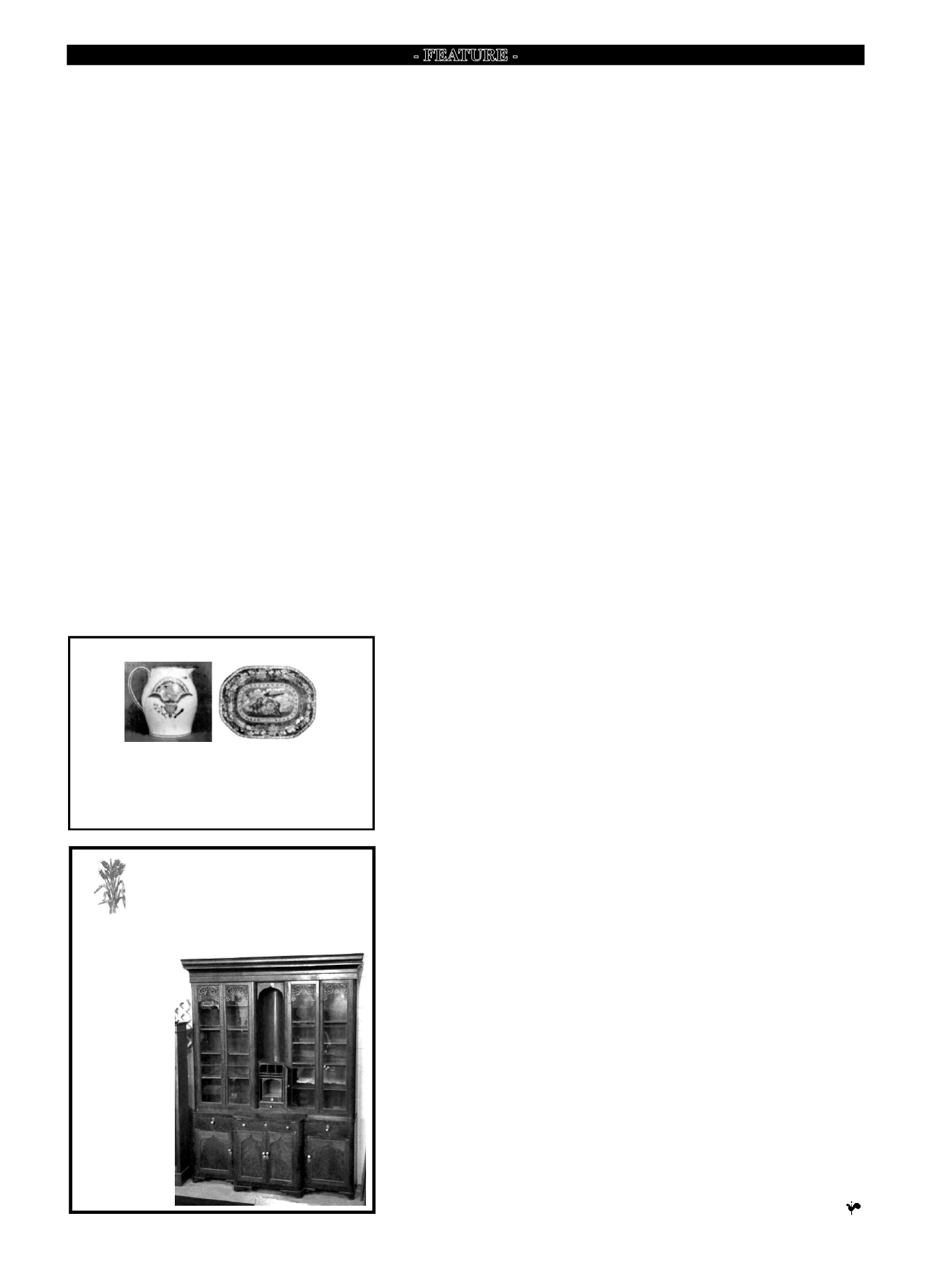

A Classical Carved

and Veneered

Mahogany

Gentleman’s

Breakfront Secretary

Bookcase. Signed and

dated by Springfield,

MA cabinetmaker

Louis Fieder, 1848.