12-A Maine Antique Digest, April 2015

by Mark Sisco

T

he next time you’re driving on Route

1 into Searsport, Maine, take heed of

the 25 m.p.h. speed limit sign as you’re

approaching the town. Just south of the

center of town, slow down and notice the

big white house and barn with the red and

white awnings and the Pumpkin Patch

Antiques sign.

That’s where Phyllis Sommer has

staked her open flag for the past four de-

cades. April 25 marks the start of her 40th

year in the business, first as a single-own-

er antiques shop, and nine years later as a

group shop housing 12 high- quality deal-

ers. Phyllis started the business with her

husband, Robert, who passed away about

17 years ago, and Phyllis has been the

sole owner and head honcho ever since.

“My husband and I started it, and for

the first nine years, we just worked it

alone, and we were learning as we went

along,” she said. “We brought with us an

interest and a passion but not a tremen-

dous amount of knowledge.”

It was Robert’s idea to broaden the

appeal of the shop by bringing in other

dealers with other ranges of expertise.

So after nine years of husband-and-wife

operation, they brought in five exhibitors.

With the addition of a new barn, the num-

ber of dealers peaked in the late ’80s, and

now she’s settled into a comfortable level

of 12.

She’s a hands-on manager, and her

exhibiting clientele is loyal. Emery Goff

and Bill Carhart of The Old Barn Annex,

Farmington, Maine, have been with her

for the entire 31 years

of group operation.

Most of the low-end,

part-time, or semire-

tired players have long

since vanished, and

what’s left is a strong

assortment of commit-

ted displayers, each

with his or her own

special areas of inter-

est.

“We just realized that

this was something that

was working for us and seemed to be of in-

terest to the other dealers because we don’t

require that anyone tends the shop,” she

explained. “They’re not setting up a booth.

They drop it at the door. I get to decide if

something should or should not come in,

and also I get to do all the display work,

so everything’s blended.... I’m spoiled. It’s

like Christmas, when they drop off pieces

and boxes and I get to go through it and

rejoice in it.”

Sommer’s own passion is early period

furniture. “I love looking at it and break-

ing it down, just trying to understand

where it came from and how it was con-

structed and what that tells us about it....

It feels as though it somehow encodes the

lives of people who have touched it and

loved it or built it.” But don’t expect to

find a $75,000 Chippendale highboy here.

“Very high end is not something I can sell

very well here. And low end I don’t like,

and I don’t want. It’s not worth bothering

with. I’m always looking for that middle

ground where there are things of interest

but more affordable.”

We’ve all witnessed the “graying of the

trade,” so to speak, but Phyllis Sommer

sees lots of hope for an upcoming new

generation of antiques lovers. Often she is

asked if children are allowed in the shop,

and her response is that an inquisitive

child presents an educative opportunity.

“When children come in and they start

looking at something, there is an oppor-

tunity to engage in a conversation if they

feel comfortable with that, and those are

the things that have to happen so we can

foster the passion in these things.” She’s

also hopeful that the passion has taken

root with her son, who will probably be

the next family business manager.

“If you’re not [dealing] serious[ly], then

I think you’re kind of siphoning off pieces

that really are the livelihood of those of us

who are professional dealers, and we’re

making a living from it.” She concluded,

“Hopefully we’ll recover and we’ll all be

able to find the next generation.”

For more information, call (207) 548-

6047 or e-mail

<pumpkinpatch168@yahoo.com>.

Forty Years of Sommer

“I have a wonderful relation with the dealers who are in the shop. I like what they see and

buy and bring in. I’m spoiled,” said Phyllis Sommer.

by Lita Solis-Cohen

T

wo unique sculptures stolen 32 years ago in broad

daylight from Hirschl & Adler Galleries in New

York City were recovered, and one of them, Paul

Manship’s

Seated Female Figure

, was shown by

Hirschl & Adler at the ADAA Art Show at the Park

Avenue Armory March 3-8.

Seated Female Figure

(1916) by Paul Manship

(1885-1966) was stolen from a Hirschl & Adler ex-

hibition of sculpture on December 2, 1983, and just

three weeks later

Figure of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whit-

ney

(1910) by Paul Troubetzkoy was stolen from the

same show in the first-floor gallery of the townhouse

at 21 East 70th Street that Hirschl & Adler then oc-

cupied. The bronze sculptures are heavy but small

enough to fit underneath a trench coat.

The thefts were reported to the Art Loss Register at

the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR)

and the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA).

Each was valued at about $24,000. They are now

worth about five times as much.

The two sculptures were consigned for sale in De-

cember 2014 to Gerald Peters Gallery in New York

City, where Alice Levi Duncan, who heads Peters’

sculpture department, began to catalog them, expect-

ing to take them to the Winter Antiques Show. Duncan

said in a phone interview that she remembered she had

sold the Manship at Christie’s when she was head of

the sculpture department about 35 years ago. “I went

to my catalog and found that I had written Hirschl and

Adler was the buyer. I knew it was a unique piece, so

I called Hirschl and Adler and learned it had been sto-

len,” said Duncan on the phone.

Hirschl & Adler contacted Christopher Marinello at

Art Recovery International in London. After serving

as general counsel for the Art Loss Register for sev-

en years, in 2013 Marinello formed the London-based

partnership specializing in stolen, missing, and looted

works of art.

Marinello negotiated among all the parties and re-

solved this dispute. “He was very gentle with the con-

signors,” said Duncan.

The anonymous collector who consigned the sculp-

tures to Gerald Peters told Marinello the two sculp-

tures had been purchased at a store in the Diamond

District approximately 30 years ago; the collector was

unaware that they had been stolen and did not have a

receipt. The identity of the thief was never discovered.

The works were returned to Hirschl &Adler on Feb-

ruary 6, and the Manship was on the gallery’s stand at

the ADAA Art Show a month later. “It fit in with our

theme, Winold Reiss and Jazz Age Modernism,” said

Eric Baumgartner, vice president at Hirschl & Adler.

“We featured the work of Reiss and other Jazz Age

artists.”

The Manship is a smaller version of a figure that

appears in his monumental bronze sundial

Time and

Manship and Troubetzkoy Sculptures Recovered 32 Years after Being Stolen

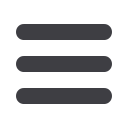

Paul Manship,

Seated Female Figure

,

9¾" high x 11 5/8" wide x 6 5/8" deep,

on a 2" high marble base. It would fit

underneath a trench coat.

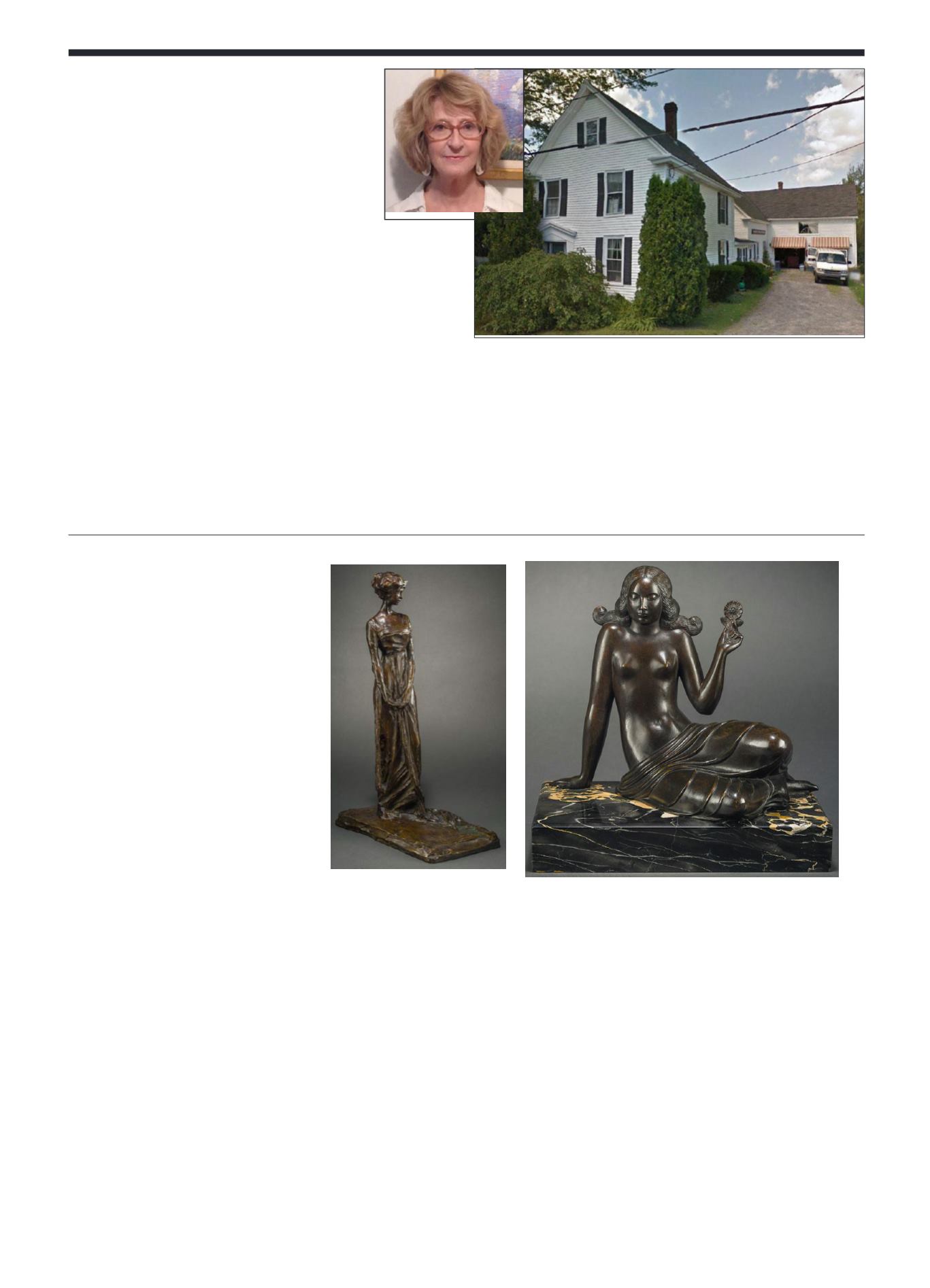

Paul Troubetzkoy,

Gertrude Vanderbilt

Whitney

, 21" high x 7½" wide x 12¾"

deep. Eric Baumgartner said the

sculptures were stolen before Hirschl

& Adler had a guard at the front door.

the Dancing Hours,

made for the

1939 New York World’s Fair

.

“

The

Seated Female

figure shows Man-

ship’s connection to archaic Greek

sculpture, seen here especially in the

stylized hair and simplified facial

features. Her pose is pure Art Deco,”

said Baumgartner. He noted that “the

small bronze predates more than a

decade Manship’s best-known public

monument art,

Prometheus

, the focal

point of Rockefeller Center in New

York.”

The sculptor and painter Prince

Paul Troubetzkoy (1866-1938),

whose father was Russian nobility

and mother was an American, lived

in Milan, taught in Moscow, and

moved to Paris in 1906, returning to

Lake Maggiore in the Alps during

summers. He made portrait busts and

statuettes of famous people such as

Tolstoy and Anatole France, and of

elegant women, including several

Vanderbilts. He lived in the United

States from 1914 to 1920 and then

returned to Europe. His best-known

work is a statue of Tsar Alexander III

in St. Petersburg in front of the Mar-

ble Palace. His bronzes of Vander-

bilts were included in an exhibition

of his sculpture at the Art Institute of

Chicago in February 1912 and at the

Detroit Museum of Art in February

1916.

“Cases like these should prove to

loss victims that is it never too late to

pursue a claim,” said Marinello in a

prepared press release. “Thirty years

is a long time for something to go

missing in the art world, but thanks to

more and more galleries undertaking

their due diligence we have a better

chance than ever of recovering long-

lost works of art.”

Marinello went on to say that the

legal process of determining owner-

ship in this case presented very few

obstacles. “Unlike the legal systems

in most European countries, it is a ba-

sic tenet of U.S. law that no individ-

ual can obtain good title to a stolen

work of art—even when purchased in

good faith. The law recognizes that a

stolen work of art is always stolen

property and therefore makes no ex-

ceptions for good faith, passage of

time, or the number of owners since

the theft occurred.”

According to Art Recovery Inter-

national this is not the first time Paul

Manship bronzes have been stolen

in New York City. In 1990 the

New

York Times

reported the recovery of

Aries and Taurus from the “Armillary

Sphere” series created for the 1964

World’s Fair. They had been stolen

along with six others from the same

series. All the missing Manships are

recorded on ArtClaim Database, the

sister business of Art Recovery In-

ternational. Loss registrations on the

recently launched ArtClaim Database

are free of charge to all users.

Art Recovery Group can be found

at 9 Clifford Street, London W1S

2FT. Visit the Web site

(www.artrecovery.com) or e-mail

<chris@artrecovery.com>.