Maine Antique Digest, April 2015 23-C

- FEATURE -

with a name or initials may also

have carved images. These will

be discussed later. And some

books have two names or two

sets of initials, possibly one the

maker or giver and the other the

recipient.

Religious inscriptions, some-

times accompanied by Chris-

tian iconography, are also

common. “Holy Bible” is the

most common title but usually

shortened to “Bible” on very

small books. Thirty-five books

(of 279) have “Holy Bible”

or “Bible” inscribed. Many

inscriptions are simple yet pow-

erful. These include “Remember

Me,” “Forget Me Not,” “Friend-

ship,” “To Mother,” “Good

Luck,” “In God We Trust,” “It Is

God’s Way,” “A Kiss,” “To One

I Love,” “God Is Love,” “You

and I,” and “From a Friend,”

to name but a few. Books with

these inscriptions are reminis-

cent of gravestones and the knit-

work mottoes common to most

American homes from the Civil

War period through the early

20th century. Since the books are

much smaller than gravestones,

their titles are abbreviated, yet

they express profound hopes and

wishes.

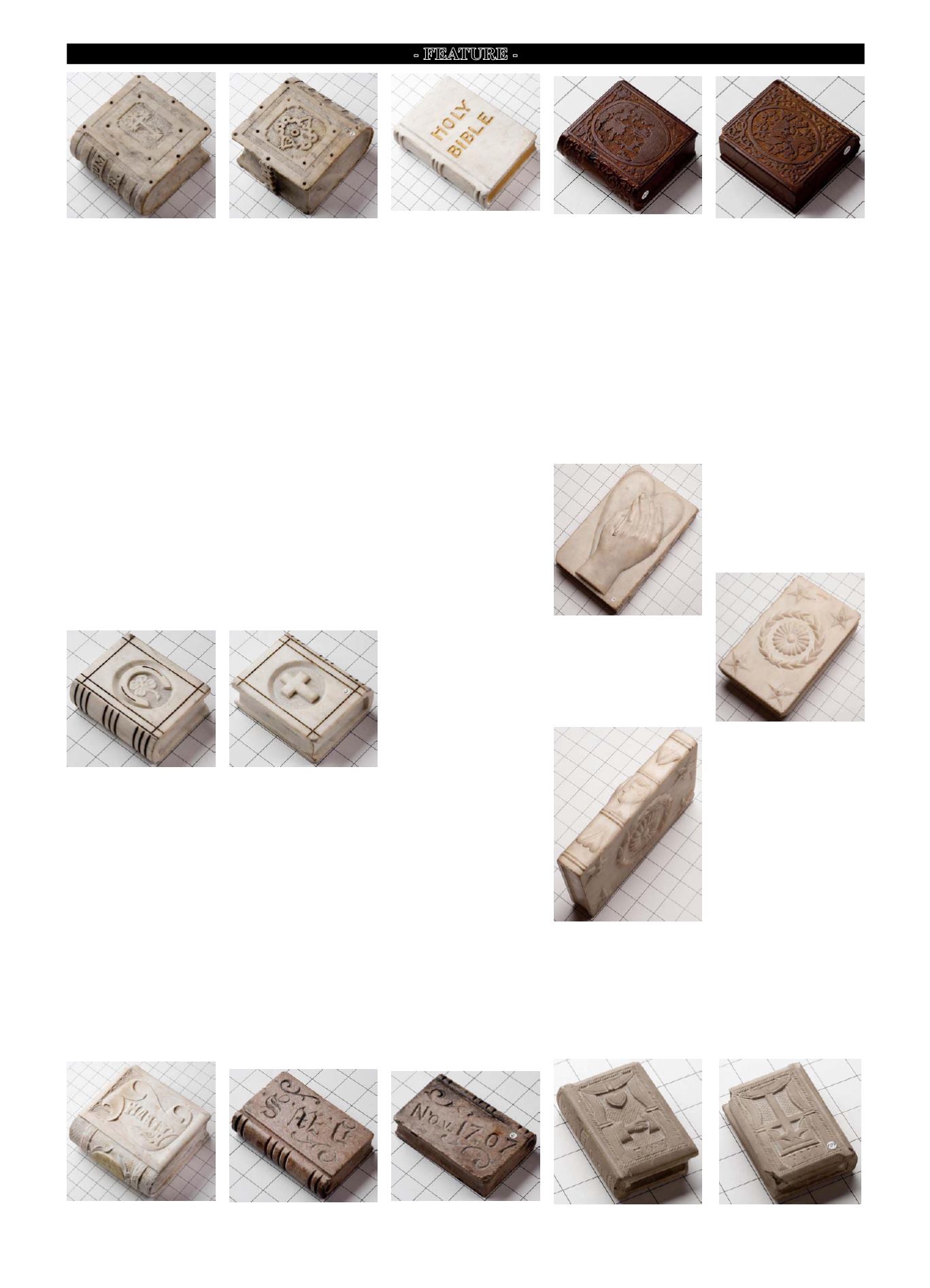

Two styles of lettering are

usually found on stone books,

block lettering or a highly dec-

orative Gothic Revival script.

The Gothic Revival lettering

style was very popular in the

second half of the 19th century.

It was common to many printed

materials, such as the title pages

of books, sheet music, adver-

tising, and religious ephemera.

The lettering on stone books

can be either incised or carved

in relief. Block lettering is more

commonly seen in relief than the

Gothic Revival style, because

relief carving is a more diffi-

cult technique. In many cases,

incised lettering of either style is

accentuated and enhanced with

bronze paint or gilding.

Dated personal stone books

are uncommon, but those with

dates typically show only the

year. A precise date is very rare;

these denote an important life

event, such as an anniversary,

birth, or death date. Sixty-five of

the 279 books in my collection

have inscribed dates, but 18 of

those are souvenir books, which

are usually dated. The earliest

dated personal book in my col-

lection has “1858.” The majority

of stone books carry dates rang-

ing from 1870 to about 1900.

The latest dated book in my col-

lection is from 1939. Most sou-

venir books are dated between

1900 and 1910.

Imagery

The most common images

on stone books are floral (99),

usually in the form of stylized

vines or branches with or with-

out flowers. Some of these are in

extremely high relief and exhibit

extraordinary carving skills.

The next most common are

religious motifs such as crosses

(34), anchors (8), and crowns.

The meaning of the cross and

the crown is obvious, but the

depiction of an anchor is usually

symbolic of hope, rather than a

nautical reference. A few have

the word “Hope” on or below

the anchor. A heart or hearts

(24 in my collection) is another

common motif, signifying love

or life but sometimes used pri-

marily as a decorative motif.

When used in combination with

a cross and/or anchor, the heart

symbolizes faith. Clasped hands

(17) are occasionally seen, usu-

ally with one female and one

male cuff, and not surprisingly,

similarly carved on gravestones

as representing the conviction

that death is only a temporary

separation. Ten books have

incised horseshoes, some with

an explicit “Good Luck” and

others with a clover leaf. Several

books are titled “Album.” Those

are large and thick and resemble

photo albums in their decoration;

several even have realistically

carved clasps.

Many stone books are embel-

lished with a combination of let-

tering and pictorial motifs, such

as initials with floral carving.

One of the most beautiful books

in the collection has a realistic

high-relief carving of a hand

holding a pen on a heart, signify-

ing writing on the heart.

Fraternal organizations’ ini-

tials or symbols are rarely seen.

My collection has only nine

books with Masonic compass

and square motifs or IOOF

symbols,

5

which seems sur-

prising given the large number

of fraternal order members in

America in the 19th and early

20th centuries. The scarcity of

stone books relating to fraternal

orders confirms my speculation

that they were principally made

as gifts to women, since few

women were involved in frater-

nal organizations.

It appears that some soldiers

in the Civil War, on both sides,

carved small (1" to 2" in height)

stone books that they likely car-

ried with them out of piety or

for good luck. They are very

scarce, crudely carved, with

dates (1863 and 1864) scratched

in, and sometimes with a place

name (“Chattanooga”). The

Museum of the Confederacy in

Richmond, Virginia, has three

of them, and there are five in my

collection. These books, carved

during the Civil War, should not

be confused with stone books

carved much later for veterans’

reunions, which were described

earlier in this article. The

Dallas

Morning News

in 1896, under

“Confederate Relics,” notes a

number of items contributed to

the Texas room of the Museum

of the Confederacy including a

“carved book, done in prison.”

6

Some stone books appear to

be memorials. Six books in my

collection have tintypes inset

into the cover, with a male name

under one. “Remember Me” and

“Forget Me Not” are uncommon

yet striking in their poignancy.

Clasped hands, as mentioned,

were a popular motif. Three

books in my collection are

explicit memorials: one to the

sinking of the Maine (“Remembr

[sic] the Maine”) and two to Wil-

liam McKinley’s assassination

(“It Is God’s Way / His Will Be

Done…”). Surprisingly, I have

never seen any books referring

to President Garfield’s assassina-

tion (1881), a period when stone

books were apparently popular.

An on-line search of digi-

tized old newspapers revealed

some surprising items, includ-

ing three accounts of prisoners

carving stone books while in

prison. According to an article

in the

Decatur Review

in 1910,

a prisoner who was convicted

of murder made a gift of a stone

Bible to the state attorney gen-

eral.

7

In another article, in the

Nevada State Journal

in 1882, a

prisoner convicted of homicide

gave a stone Bible to the sheriff.

8

A third article, in the

New York

Sun

, dated October 12, 1896,

describes an account involving

a stone Bible: “Finally six of

the gang, including Reno, were

captured at Jeffersonville, in the

southern part of the State. Five

were hanged by a mob. Reno

made his escape, went to Mis-

souri, was arrested on another

charge, and was sent to the pen-

itentiary. He served his time and

then came back into Indiana.

Walking into the office of the

general manager of the express

company, which was then at Cin-

cinnati, he carried in his hand a

large package. He made himself

known to the official, and then

opened his package. ‘See this,’

said he. ‘It is a stone Bible which

I cut while in the penitentiary.

I bring it to show to you that I

have reformed, that I believe in

its teachings, and that I will for-

ever in the future be a good man.

Will you let me go? If not, I am

here to take my medicine.’”

9

One large, beautifully carved

limestone book in my collection

is marked “Prison Life in Ana-

mosa,” the location of the Iowa

State Penitentiary. An older Iowa

dealer told me that while he has

seen several of these Anamosa

books, documented prison books

remain rare.

Of the approximately 15 men-

tions of stone books in various

late 19th- and early 20th-century

newspapers, none had explana-

tions of stone books, which sug-

gests that the books were widely

distributed and recognized.

As mentioned earlier, some

stone books were created as

souvenirs for tourists visiting

popular sites, such as Garden

of the Gods, scenic rock for-

mations near Colorado Springs,

and French Lick Springs and

West Baden, resorts in southern

Indiana. These were turned out

in relatively large numbers and

are marked with the site name

and usually dated in the range

of 1900 to 1910. Most souvenir

books are small, usually 2" high

x 1½", with amateurishly carved

inscriptions.

Stone books were made in

many countries, and their dec-

orative motifs and inscriptions

often give clues to their origin.

Although I focus on American

stone books, my collection con-

tains some books that clearly

were made elsewhere. There are

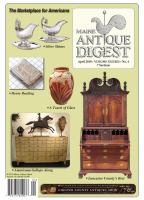

Relief cross (front); relief knot (back); “Album / 1883” (spine). Note

clasp and drilled decoration. Massive book.

“HOLY / BIBLE” with incised

gilt letters.

Relief deer in landscape (front); birds in tree (back). Note crisp carv-

ing. Catlinite (pipestone).

Relief horseshoe with clover (front); cross (back).

“Album” on scroll in high relief.

Massive book.

Neo-Gothic initials (front); “Nov. 17, 07” (back).

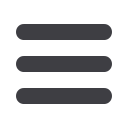

Deeply carved clasped hands between curtains (front); cross between

curtains (back); “LOVE” (spine).

High-relief hand holding a pen

and writing on a heart (front);

stars, wreath, blossom (back);

hearts and male’s head in relief

(spine). Beautifully carved, sculp-

tural. Note contrast between aca-

demic carving of the hand and the

folky back and spine. As good as it

gets with books.

☞