22-C Maine Antique Digest, April 2015

- FEATURE -

Carved in Stone: American Stone Books

by Ian Berke

All books were photographed on a 1" grid for scale.

A

bout eight years ago at a

New England antiques

show, I saw a small,

carved white marble book with

“Remembr [sic] the Maine”

inscribed on its front cover. The

same dealer also had a similar

book that featured a profile of

William McKinley and seemed

to be a memorial to his assassina-

tion in 1901. I had never noticed

stone books before, much less

those with historical connec-

tions, and was intrigued, in part

because of my background in

geology. I had to buy them both,

and thus began a search for stone

books that has never stopped. In

this article, I will discuss Ameri-

can stone books and my attempt

to understand this unique form

of folk art.

Carved stone books are a

fascinating and unusual form

of American folk art, which,

loosely defined, is traditional

artistic expression lavished on

common utilitarian objects.

Unlike many of the objects now

considered folk art, stone books

were not intended for any sig-

nificant practical purpose other

than as objects of remembrance.

The custom of making objects

of remembrance and tokens

of love runs deep in the reper-

toire of traditional craftsmen.

Some 19th-century American

craftsmen produced so-called

whimsies, which are fanciful

works done after normal work-

ing hours, using their surplus

or scrap material. Glassblowers

made canes, rolling pins, deco-

rative balls, and other decorative

items. Sewer tile workers are

recognized today for their small

clay animals. Whalers made

scrimshaw and knotted figures.

These items were labors of love,

usually intended as gifts for

friends and family.

Stonecutters, many of whom

worked in gravestone shops,

created whimsies in the form of

small carved stone books. Some

of these stone books were blank,

while others were beautifully

embellished and imbued with

great feeling, as they were made

as gifts and memorials. One of

our most powerful impulses is

our desire to love, to be loved,

and to be remembered. Per-

haps a stone book was a way

for some stonecutters and oth-

ers to express their feelings, not

intended or used as hand warm-

ers but as heart warmers. It also

seems clear that some stonecut-

ters made more than one or two

books. I have seen a number of

stone books clearly made by the

same hand. For instance, two

McKinley memorial books in

my collection have obviously

been made by the same person.

Another carver used very dis-

tinctive birds within a rope-like

border on multiple books.

Skillfully done books would

likely have been highly desired

as gifts, so it is probable that the

cutters sold some of their books

to others who gave them as spe-

cial gifts to friends.

Some notable stone book gifts

were mentioned in the press.

For example, in 1892, the soci-

ety gossip column of the

Daily

Democrat

of Hamilton, Ohio,

states that Mr. and Mrs. Andrew

Kuhlman received an “elegant

stone book” as one of their wed-

ding gifts.

1

Another story that

describes stone books as gifts

was printed in a 1929 issue of

an Iowa newspaper: “My father

had an employee—a common

quarry man—who was an artist

to his fingertips. At odd times he

would carve beautifully in stone.

When my father went west this

man made, as a parting gift, a

stone Bible of fairy frostlike

carving, deeply undercarved,

beautiful and perfect. It was in

our family a lifetime.”

2

Stone books are typically

small, averaging about 3

"

to 5

"

high. They were nearly always

carved in a closed position, often

in white marble, with the covers

and pages carefully delineated.

Stone books have a variety of

inscriptions and images. They

can be carved with monograms,

full names, religious titles (“Holy

Bible”), good wishes (“Good

Luck,” “Friendship,” etc.), and

sometimes the dates of their cre-

ation or events. Stone books are

also carved with pictorial motifs

of a religious or secular nature.

Crosses, horseshoes, flowers,

animals, hearts, and geometric

designs are the most common

designs seen on stone books.

Evidence that professional stone-

cutters carved books is the high

quality of many of the inscrip-

tions and images. Doubtless, not

all stone books were carved by

stonecutters, as evidenced by a

substantial number with much

less skilled carving, sometimes

awkward. Yet inscriptions and

carving are not common; most

books are blank. About a third

of the personal books (meaning

those that are carved for individ-

ual gifts, rather than souvenir or

advertising books) I have seen

have inscriptions or images.

While most stone books were

likely intended as gifts, even

if not actually carved by the

giver, not all stone books are of

a personal nature. Some were

intended to be sold as tourist sou-

venirs at popular destinations,

such the Garden of the Gods.

These “tourist” books are fairly

common. Others were done for

business advertising, but these

are uncommon. There are also

books done by civil prisoners

and prisoners of war. These will

be discussed later in this article.

Many types of stone were used

in the making of stone books.

The most common is white mar-

ble, which is logical given its

widespread availability through-

out the United States as a result

of the growth of the railroads by

the 1870s. All but the smallest

towns would have had a monu-

ment maker. Marble is relatively

soft (hardness of 3, Mohs scale),

and every gravestone maker had

scraps. White is also symbolic of

purity, therefore an appropriate

choice for making stone books

with Christian references.

Ornamental marbles were

used occasionally. These include

brecciated, red fossil, deep gray,

and green Vermont marbles,

but these are less common than

white marble. Alabaster, an even

softer stone, often translucent, is

seen as well. Fine-grained lime-

stone and sandstone, sometimes

very dark in color, are common,

and these are probably from the

Midwest, judging from the num-

ber found by Midwest dealers.

Catlinite, or pipestone, a very

soft stone with its characteristic

red color resulting from its iron

oxide content, was also used.

Slate, despite being a common

early headstone material, is

rarely seen. Soapstone is also

rare. Anthracite, fossil coal, and

fossil coral were occasionally

used, but all are rare. Igneous

rocks, such as granite, are very

rare in stone book form pre-

sumably because they are much

harder and so much more dif-

ficult to carve. No carver with

19th-century tools could carve

granite with the beautiful detail

often seen in marble. Agate,

although very hard, is sometimes

seen in very small books, usually

without inscriptions. Some of

the tiny agate books were used

as fobs.

What does a carved book

symbolize? The most common

book in America in the 19th cen-

tury was the Bible, and a carved

book, even without explicit reli-

gious imagery, would surely

be recognized as a symbol of

a Bible. Nearly all stone books

were carved in a closed position

rather than open. The customary

closed position was chosen prob-

ably because it is easier to carve

and engrave and more compact

than an open book. A closed

Bible is perhaps symbolic of the

belief that only God can know

the future, hence a closed book.

I have attempted an analysis

of the 279 stone books currently

in my collection, based on the

inscriptions, images, and dates.

Admittedly this is not an accu-

rate representation of all stone

books, as the act of collecting

assumes a certain selectivity,

which skews a collection toward

the unique and best examples.

Still, the analysis indicates some

interesting trends.

It will not escape any read-

er’s eye that these conclusions

are educated guesses, because

even after assembling a collec-

tion of 279 stone books (as of

July 2014), I have yet to find

one stone book with a prove-

nance. Two other collections I

know of, one of which I have

personally seen, each with about

100 books, have only two books

with a documented provenance.

Most stone books are objects

that, sadly, are likely to remain

anonymous once they leave their

original family. They were triv-

ial in economic value, so they

do not show up in death invento-

ries. Further, with the exception

of a fairly recent article in

Early

American Life

, “Books Never

Read” by Winfield Ross,

3

noth-

ing has been published about

stone books, and most curators

are completely unaware of them.

I know of only three institutions

with examples of stone books

in their collections: one book at

Historic New England,

4

three at

the Museum of the Confederacy

in Richmond, Virginia, and two

at Winterthur (likely Italian).

Very few stone books give a clue

to their geographic origin, other

than those with town names,

which are typically souvenir

objects. The exceptions are the

pipestone books, since the stone

is quarried in Minnesota, and

the other tourist books inscribed

with the site names.

It seems safe to assume

that stone books were carved

throughout the United States, but

they are most commonly found

today in the Midwest and New

England. One might expect a tra-

dition of carving stone books in

two regions where stone carving

and folk art are prevalent, Ver-

mont and Pennsylvania Dutch

country in southeastern Pennsyl-

vania. Central Vermont was an

important source of marble, both

of ornamental and dimension

stone, so one might expect a tra-

dition of carving stone whimsies,

such as books. But several trips to

the Dorset area and the Vermont

Marble Museum in Proctor did

not turn up any examples. Nor

have antiques dealers located in

Vermont turned up a dispropor-

tionate number of stone books

in relation to dealers elsewhere.

Most antiques dealers in south-

eastern Pennsylvania had never

seen stone books in their area.

Inscriptions

Stone books are decorated

with many inscriptions and

images that are both incised into

the stone and carved in relief.

Initials and names are usually

singular, but sometimes there

are two sets of initials or names,

which probably represent the

giver and the recipient. The most

common inscriptions found on

stone books are initials (63 of

279 books), followed by first

names (30), full names (21), last

names with initials (10), and

finally dates (65). Full names are

less common than first names,

perhaps because these books

were intended as gifts from the

makers, who surely knew the

intended recipient well. Most

first names are female. Out of 30

books with first names, 23 are

female; but out of 21 full names,

only seven are female. It seems

logical that more women than

men were the recipients of these

books, as the makers were likely

all men.

Initials and last names with

only first initials give no clue

as to gender, but a reasonable

presumption is that most are

male. Several are inscribed with

“Mother.” One book has two sets

of initials, followed by a third set,

underneath, reading “BORN /

AP. 6, 1875,” which probably

represent the parents’ initials,

followed by the newborn. Most

of the full names are relatively

common, so it has been impos-

sible to connect them with a spe-

cific person. However, one book

with the unusual name “Sybilla

Ruen” was enough information

for a friend skilled in genea-

logical research to identify it

as belonging to a housewife in

Ottoville, Ohio, who died in

1916. Another book, done by or

for a Civil War veteran at a GAR

convention in 1912, was also tied

to that specific veteran, Captain

Sosman, who fought with the

22nd Ohio Volunteer Regiment.

Often initials and names are

incised, but sometimes they are

done in relief. Of course a book

Carved stone

books are a

fascinating and

unusual form of

American folk

art.

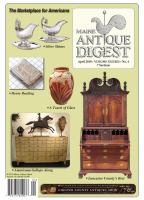

“Remembr [sic] the Maine” in

relief letters.

High-relief floral carving.

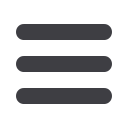

Initials in neo-Gothic style.

Heart with initials and “stitched”

decoration.

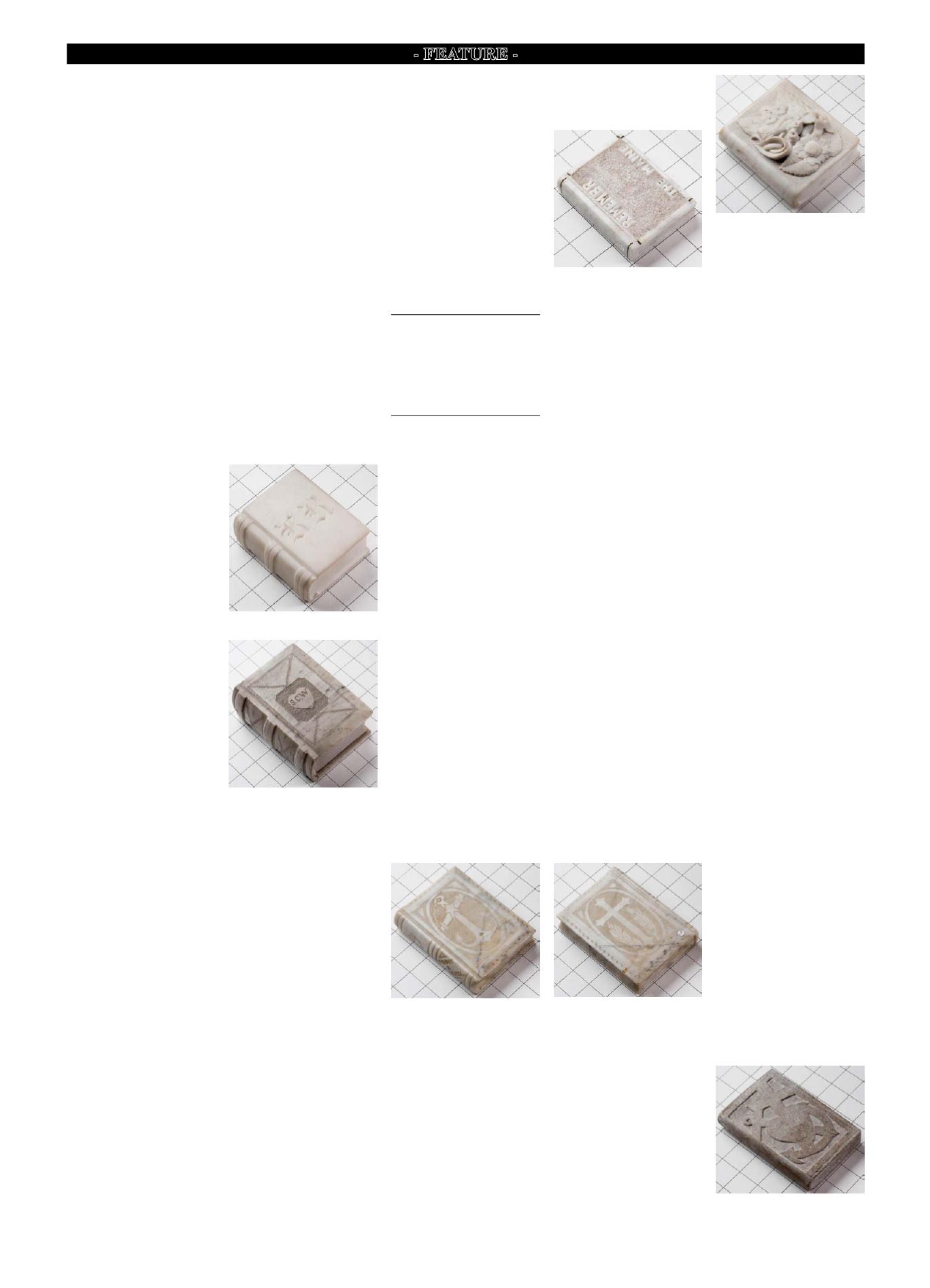

Low-relief anchor (front); cross (back).

Relief anchor, cross, and heart

(“HOPE”).