10-B Maine Antique Digest, April 2017

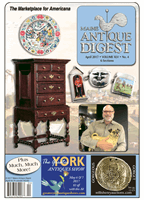

-

FEATURE -

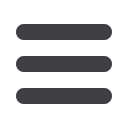

10-B

Rosetta Stone Sketchbook

by Tompkins H. Matteson Rediscovered

by Christine Oaklander

F

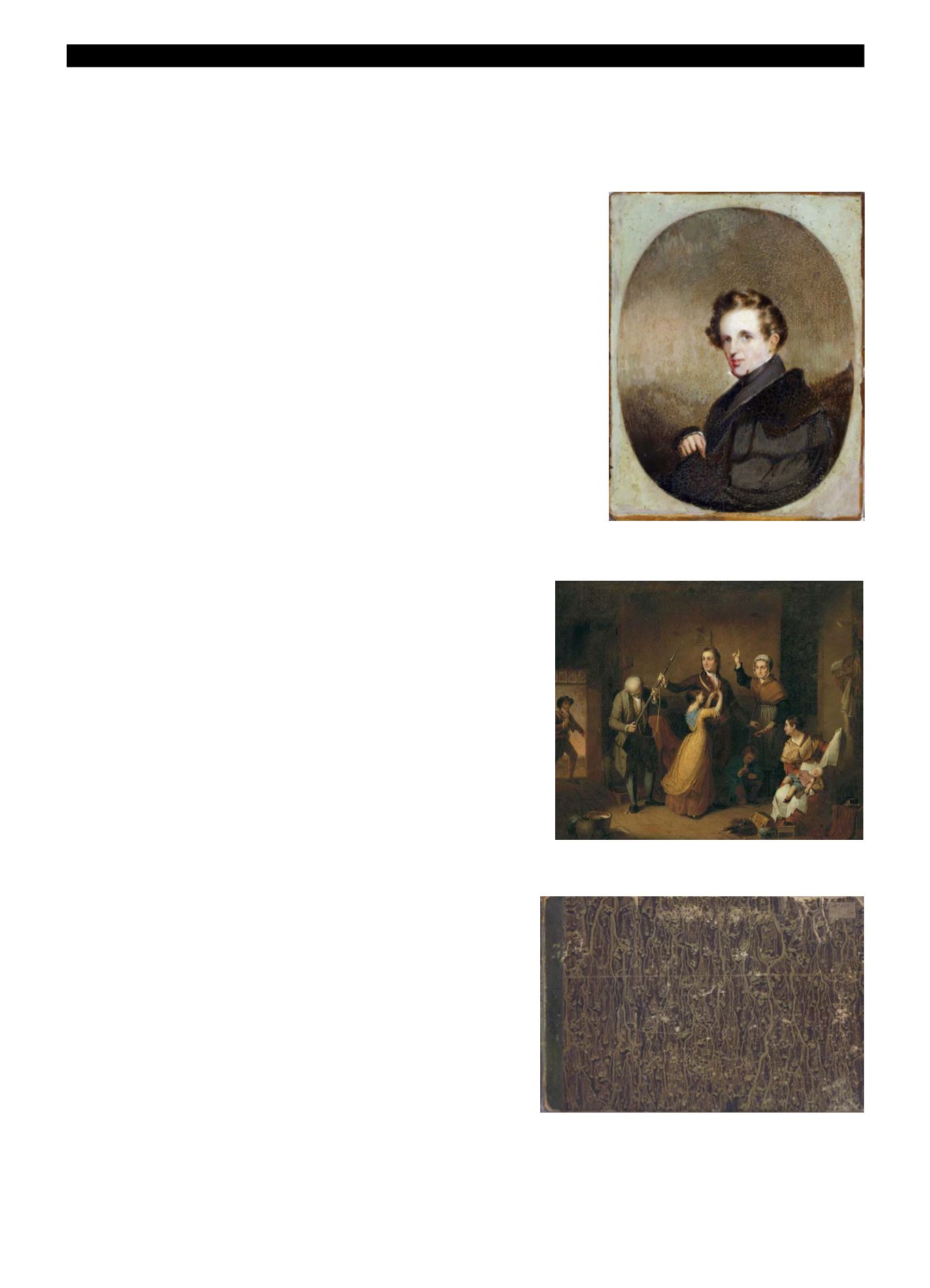

rom my point of view, 2016 was the year for the

prominent American genre and historical painter

Tompkins H. Matteson (1813-1884).

1

In the

March issue of

Maine Antique Digest

I spotted a small

advertisement by Axtell Antiques (p. 12-CS) offering a

self-portrait of the artist as a youngman.With a handsome,

Byronic look conveyed by wavy chestnut hair, a creamy

complexion, and a piercing eye, the portrait is inscribed

on the back of the board “painted by Mattison 1838.”

2

It is fairly well rendered, demonstrating the artist’s

experience in the late 1830s drawing after the antique at

the National Academy of Design during a sojourn in New

York City. It dates to his early career spent as a portrait

painter, before he achieved a reputation for his historical

and literary genre subjects. Before the invention of the

daguerreotype, artists traveled from town to town, set up

shop for a few weeks, and captured likenesses to order.

For most artists this nomadic lifestyle was the only way

to earn one’s bread and butter. Seeing the advertisement

about a month after it was published, I was delighted to

learn that the portrait was still available from Richard

Axtell. I made a 150-mile trip north to inspect and

purchase it.

The next month Doyle New York offered an important

1845 patriotic theme painting by Matteson not publicly

seen indecades,

TheSpirit of ’76

. ScholarDonaldD.Keyes

described this painting as one of the two that launched

Matteson’s career.

3

Estimated at $10,000/15,000, the

painting sold for a stunning $149,000 and affirmed the

enduring appeal of Revolutionary War imagery.

M.A.D.

covered the sale in its June issue.

4

My connection with Matteson started in the 1980s,

when I worked in the department of painting and sculpture

at the New-York Historical Society, repository for one of

Matteson’s most striking compositions,

Last of His Race

,

an 1847 oil on canvas. It is a rendition of NativeAmerican

costume, life, and history with an obvious allusion to

Manifest Destiny. This was one of my favorite paintings

during the almost three years I worked at the society. In

2001, as director of collections and exhibitions at the

Allentown Art Museum, the second painting I acquired

for the permanent collection was Matteson’s

Return of

Rip Van Winkle

(circa 1845), an illustration for one of

Washington Irving’s best-loved stories.

5

Learning that the

public library in Matteson’s central New York hometown

of Sherburne owned several of his paintings, I inquired

if the paintings were accessible. I wanted to make a road

trip to see them, but life and a demanding job intervened

and I did not.

Fast forward to 2014. I purchased a collection of

art and archival materials from the estate of the long-

forgotten American artist Henry Grant Plumb (1847-

1930) and learned with incredulity that he and Matteson

were both from Sherburne, New York. Now I was

compelled to make that 180-mile drive to the Sherburne

Public Library to view Matteson’s genre paintings and

Plumb’s portraits and landscapes, where they keep

company in the library’s spacious main reading room.

Thus I commenced a series of trips to the magical yet tiny

town of Sherburne, where I read issues of the

Sherburne

News

, founded in 1864 and still published by the same

family for over a century. It’s a rich source of information

about the town and surrounding Chenango County. I also

met descendants of current or former owners of artwork

by Plumb and Matteson and interviewed experts about

the town’s history.

A key piece of the Plumb puzzle has been to determine

what influence Matteson had on the younger artist.

We know that he was closely linked with Plumb’s

father, Isaac, since both were leaders in local and

regional politics, founders and foremen of the first fire

departments in Sherburne, and trustees of the school

board.

6

Lastly, Matteson gave art lessons at his Sherburne

studio. Surprisingly, none of Plumb’s biographical entries

mention Matteson, although Matteson’s portraits of

Plumb and his siblings (private collections) and Plumb’s

posthumous portrait of Matteson (location unknown)

imply a close relationship.

7

I was aware that several museums in upstate and

central New York had significant Matteson holdings,

notably the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, the

Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, and

the Albany Institute of History and Art. Nancy Simerl,

director of the Sherburne Public Library, helped connect

me with individuals owning art or archival material

related to Matteson and Plumb, informing me that some

of Matteson’s descendants, still living locally, owned

two of his sketchbooks and two oils.

8

Hearing this was

like proverbial catnip to a feline, and I prevailed on her

to make the introduction, which transpired last summer.

As it turned out, there was one sketchbook; two paintings

hung in the family’s Victorian home. The descendants

hoped I could inspect the paintings and provide an

idea of their importance and potential value. After I

completed that task, they brought out the sketchbook,

housed in a protective archival box. Measuring 9" x 6",

the hardbound book preserves 57 pages bearing pencil

drawings.

9

When riffling quickly through the sketches, I quickly

recognized with elation two drawings for a unique

and much-published painting of sculptor Erastus Dow

Palmer of Albany, New York, in his studio. A quick

assessment suggested that the sketchbook contained a

range of drawings; some appeared to be fairly detailed

preliminary versions of paintings while others were

more modest, presenting a head, a piece of furniture, or a

background landscape.

Since the owners were understandably reluctant to

turn the book over to a stranger, I took a few clumsy

photographs with my iPad mini. They were interested in

selling the book but had no idea how to approach the task

or evenwhat the book’s valuemight be.Withmore than 30

years of experience in historical American art, including

work for art dealer Ira Spanierman of New York City, I

knew that establishing value for the book would lie in

linking the drawings to Matteson’s paintings

and prints. Sketchbooks are oddball objects

and don’t have a regular market in the way

that paintings do. In this case, the book’s

provenance—with a direct line of descent

from the artist—would also confer value. The

news bite of Doyle’s record-setting Matteson

sale didn’t hurt either. With my appetite for

research and an excellent visual memory, I

was eager to undertake this project. Given

the go-ahead by the owners, I plunged in.

Soon realizing that my amateur digital

images crippled the ability to make accurate

visual comparisons, I convinced the owners

to let me take the book by promising that I

would keep it safe and inform them of my

progress. Since July 2016, I have researched

the sketchbook and made some fascinating

discoveries along the way.

Not relying just on Internet research, I

visited the Fenimore Art Museum repository

of about two dozen large Matteson drawings,

as well as conducting research at the art

division of the New York Public Library and

at Princeton University Library’s rare books

and special collections.

Princeton proved an excellent source

for information on Matteson’s published

illustrations and led me to an important

discovery. I have identified roughly two

dozen of the sketchbook drawings as

either complete preliminary renditions of

Matteson’s known paintings and prints

or portions thereof. Some of the related

paintings are known today only through

verbal descriptions, exhibition records,

biographical sketches, individual prints

after the paintings, or prints published in

magazines and books. Matteson was a

prolific popular illustrator who capitalized

on several of his paintings and drawings

that were reproduced as stand-alone prints

that were widely marketed.

10

The sketchbook has proven itself a

veritable Rosetta stone for a portion of

Matteson’s career, beginning in the late

1840s and ending in the mid-1870s. This

is noteworthy because most sketchbooks

cover just a fewmonths or perhaps a year or

two. It references his decorative religious work, including

two drawings for ornamental church hangings or theater

curtains no longer extant. It shows his dedication to fire

prevention, presenting two fire rescue scenes. In one of

Tompkins Matteson,

Self-portrait

, 1838, oil on paper laid

on panel.

Tompkins Matteson,

The Spirit of ’76

, 1845, oil on canvas. Photo

courtesy Doyle New York.

Tompkins Matteson sketchbook, front cover, 1849-70. Private collection.