Maine Antique Digest, April 2017 25-A

-

AUCTION -

35-D

(1825-1907) got the one sold this year, and

it descended to his only child, Edith Hope

Goddard (1868-1970). Edith married Charles

Oliver Iselin (1854-1932), and they took the

table with them to Upper Brookville, New

York. At her death, she bequeathed the table to

her first cousin once removed Robert H. Ives

Goddard (1909-2003), who already owned the

other Nicholas Brown table. That $8,416,000

table descended to Thomas and Hope Brown

Ives; they left the house and contents to their

son Moses Brown Ives (1794-1857), a Harvard

graduate and merchant at Brown and Ives,

and his wife, Anne Allen Dorr (1810-1884).

Moses and Anne’s daughter, Hope Brown Ives

(1839-1909), inherited the Thomas Poynton

Ives house and the table at their death. Hope

married Henry Grinnell Russell, and they lived

in the house without issue until his death circa

1905 and her death in 1909. The house and

contents then descended to her cousin Robert

H. Ives Goddard, who took up residence in the

house about 1910-11. The two tables, which

had been together for three generations before

they were separated, were reunited in 1970

on the bequest of Edith Hope Goddard Iselin.

They were in the same family for 35 years

before the first table was sold in 2005, and the

second table was sold in 2017.

There was much discussion about exactly

when this second table was made. The

cognoscenti—curators, conservators, and

Gronning—believe it was made in the 18th

century as a mate to the Goddard table by a

first-rate craftsman, probably in Providence

where Nicholas Brown lived. The top is carved

out of the solid, no easy feat, and the maker was

aware of Goddard’s shop practices. Then the

next generation added a drawer in the Federal

period. The buyer had little competition, and

this sculptural icon in the history of American

furniture was made more affordable by the

addition of a drawer.

Other documented furniture brought a

premium. A diminutive mahogany chest of

drawers with an old surface, signed by Walter

Frothingham, Charlestown, Massachusetts, and

Joseph Hallowell, circa 1760, sold for $187,500

(est. $150,000/250,000). The underside of the

long drawer bears the chalk inscription “Walter

Frothingham / Charlestown,” and on the inner

side of the backboards a chalk inscription reads

“Joseph Hallowell.” It appears to retain its

original cast brass hardware. The Frothingham

signature appears quite similar to that of

Benjamin Frothingham Jr. that appears on

a high chest in the collection of Winterthur.

Given the location of Hallowell’s signature

on the interior of the backboards, the chest of

drawers could have been inscribed only when

it was being constructed. This remarkable chest

stands as the sole surviving object identifying

Walter Frothingham and Joseph Hallowell as

likely apprentices in the workshop of master

cabinetmaker Benjamin Frothingham Jr. They

buyer was dealer Roberto Freitas of Stonington,

Connecticut, bidding for a client.

Furniture in pristine condition was

embraced. A Queen Anne veneered walnut

high chest of drawers, Ipswich, Massachusetts,

circa 1755, that appears to retain its original

finials, oversize cast brass hardware, and good

color sold for $75,000 (est. $40,000/60,000) to

a St. Louis collector in the salesroom. Much

admired at the previews, it was also shown

during American paintings week, and some

thought it might bring more.

There was something for every taste in

this sale. A rare William and Mary gumwood

kast with mahogany veneer that belonged

to Marvin Schwartz sold for $15,000 (est.

$15,000/30,000). Schwartz was the first

antiques columnist for the

New York Times,

and he also worked at the Brooklyn Museum

and the Metropolitan Museum of Art for years.

A fine Hayes family Boston games table

with an old surface sold for $43,740 (est.

$25,000/50,000). A serpentine mahogany chest

of drawers attributed to Benjamin Frothingham

sold for $50,000 (est. $40,000/60,000). A

Goddard-Townsend school tea table brought

$27,500 (est. $20,000/30,000). A pair of

Philadelphia walnut side chairs with four shells

and strapwork splats sold for $10,000 (est.

$2500/3500) to West Chester, Pennsylvania,

dealer Skip Chalfant. They were one of three

pairs of Philadelphia side chairs he bought

during the week. Apaint-decorated two-drawer

blanket chest with wild graining, circa 1810,

sold for $11,250 (est. $3000/5000), showing

that not all country furniture brings less in New

York City than in the country.

There were some high prices and some

bargains along with a new energy in the

Americana market. A lot was offered at one

time. Some said it was too much, but there

were plenty of buyers. Some prefer to come to

New York City just once a year. Some preview

and return home to bid, and some buyers never

preview in person. They pore over the online

catalogs, enlarge the images, read the condition

reports, and bid online. Others decide what they

will spend and leave a bid with the auctioneer

and often get what they want for less than their

bid.

There were some major disappointments.

The desk-and-bookcase possibly by George

Bright, Boston, Massachusetts, 1765-85, that

descended in the Lee family of Boston, with

hairy-paw feet and its original hardware,

lacking trailing garlands from its rosettes,

was estimated at $200,000/300,000 and was

passed. It had sold for $59,700 at the sale of

the Eddy Nicholson collection at Christie’s

in January 1995. A Salem desk-and-bookcase

with a $200,000/400,000 estimate also failed to

sell. A large and imposing pair of Loockerman

family mahogany drop-leaf dining tables

estimated at $200,000/300,000 found no buyer.

The pair had sold for $583,000 at

Sotheby’s in February 1985 and for

$310,500 at Christie’s in October

1996. The market at the top is thin.

For more information, call Sothe-

by’s Americana department at (212)

606-7130 or check the website

(www.sothebys.com).

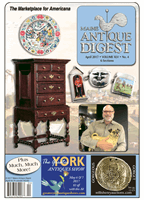

Philadelphia needlework flower picture, circa 1800, of multicolored silk, in its

original black-painted shadow box frame, 18" x 21½", sold for $212,500 (est.

$60,000/80,000) to dealer Leigh Keno on the phone, underbid in the salesroom

by Amy Finkel on the phone with a client. It is related to another silkwork

picture by Hannah Deaves that sold for $120,000 to Leigh Keno at Sotheby’s in

January 2005. They have similar rabbits and flowers.

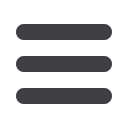

Henry Church (1836-1908),

Bountiful Table

, inscribed “H. Church

Blacksmith,” circa

1870, oil on paper set down on aluminum, 23" x 35½",

replaced frame, some inpainting and repaired tears, sold for $20,000 (est.

$25,000/50,000). Condition kept the price down.

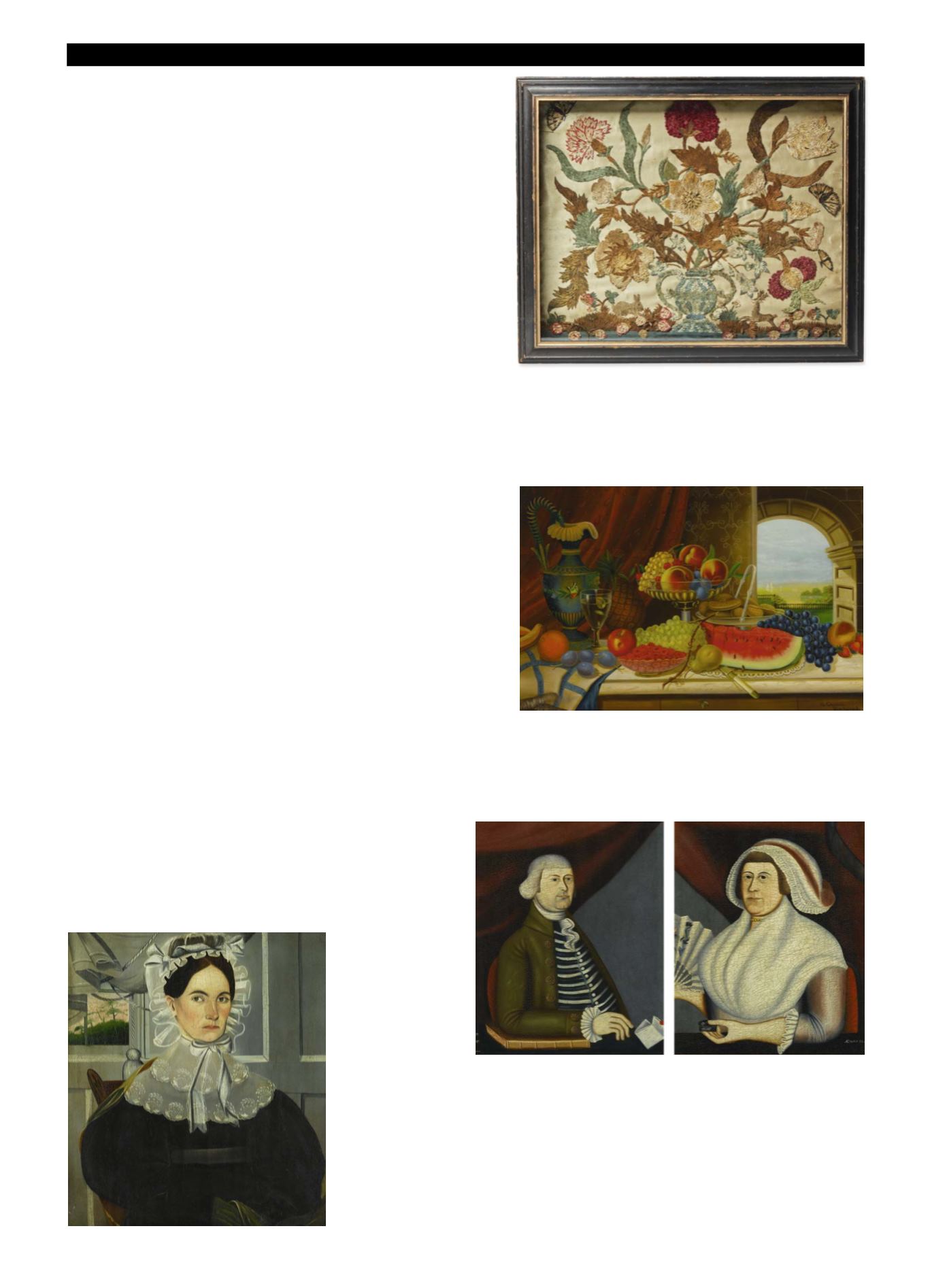

Portraits by Rufus Hathaway (1770-1822) of Captain and Mrs. Pollycarpus

Edson, oils on canvas mounted on panels, 28" x 23¼", 1791, sold on the phone

for $200,000 (est. $100,000/150,000), underbid by collectors in the salesroom.

The captain’s portrait is signed and dated; his wife’s is inscribed “Aetatis

31.” According to the catalog, Hathaway painted little after 1795, the year

he married the daughter of a prominent local merchant. Soon thereafter he

became a physician. Captain Pollycarpus Edson was named for the bishop

of Smyrna. In the portraits Edson rests his arm on his ledger book, and his

wife, Lucy Eaton, wears pearls and holds a hand-painted fan. They lived in

Bridgewater, Massachusetts, and had five children. Both paintings had been

trimmed; the captain’s portrait is smaller than the woman’s, half her fan is cut

away, but they are early well-painted likenesses. They had been for sale at Vose

Galleries in Boston for the last few years and were advertised on InCollect.

Sheldon Peck (1797-1868) painted

this 27" x 24"

oil on wood panel,

Young Woman in Paneled Room

,

around 1828-36 when he lived

in Jordan, New York. It sold for

$187,500 (est. $30,000/50,000)

to a New York collector in the

salesroom. At Northeast Auctions

in August 1996, it sold for $79,500.

Good paintings by Peck are rare;

it could be years before another

will come on the market.