16-A Maine Antique Digest, April 2017

-

FEATURE -

16-A

In the Trade

John Krynick and Francis Nestor of Cottage+

Camp, North Egremont, Massachusetts

by Frank Donegan

P

eople end up in the antiques trade for all sorts

of reasons. When it comes to John Krynick and

Francis Nestor of Cottage+Camp, North Egremont,

Massachusetts, the explanation is straightforward. “If we

didn’t have the business,” Nestor said, “we’d probably be

hoarders. We can’t get away from it. We’re both totally

drawn to objects.”

The objects they’re best known for tend to be quirky

things, often with a folky tilt. Age is sometimes less

important that the compelling visual nature of a piece.

Nestor added, “People think we’re randomly eclectic,

but to us it makes a lot of sense.” He also noted that

his opinion isn’t universally shared. “We were doing a

show one time and overheard one person whispering to

another, ‘Don’t go in there. It’s voodoo.’”

He explained their approach. “We have a bunch of

separate categories.” For instance, he said, “We love

quilts, but you’re not going to see us with a pile of

Nine Patch or Drunkard’s Path quilts.” Some of their

categories are less conventional. Take dogs, for example.

Krynick and Nestor don’t usually buy ceramics, but if a

ceramic piece has a nice dog on it, they’re likely buyers.

“We like dogs,” Nestor said. They also like ephemeral

political stuff as long as it packs a visual punch.

They don’t buy a lot of furniture, but when they do,

it’s more likely because they view the piece as a discrete

sculptural object or as an example of folk art. “We had

a rule,” Nestor said. “If the two of us can’t lift it, we

shouldn’t buy it. We must have been in the business for

ten years and somebody said, ‘Oh my God! You actually

have a case piece.’”

Over the years, the couple has moved the business

around a fair amount: first it was in Boston; then in

Woodstock, New York, for 14 years, during which time

they had two different shops in town over a five-year

period; then a space in Hudson, New York; followed by

a decade in Philadelphia. Recently, they bought an 1887

Baptist church that had run out of Baptists in the historic

village of North Egremont. The church had about 250

members when it was built but was down to six when

Krynick and Nestor purchased the place last summer.

“We moved in on July Fourth,” Nestor said.

It may be a bit of a stretch to call North Egremont

a village. There seems to be only one store—the Old

Egremont Country Store—in the place. But it’s certainly

historic. It’s on the National Register of Historic Places,

and it’s on the route that Colonel Henry Knox took in

the winter of 1775, when his troops dragged 60 tons

of cannons and armaments through the snow to fortify

Dorchester Heights, which allowed George Washington

to drive the British out of Boston.

Fitting out a church as a home is not necessarily an

easy process. This one had a kitchen in the parish meeting

hall, but there was no full bathroom. “We were without

a bathroom for eleven weeks,” Nestor said. When we

visited in late January, he noted, “The port-a-potty just

went down the road.”

The new residence will no doubt affect how they

conduct business. In the past they have often had open

shops, but they won’t have one here. “We looked into

it, but zoning got complicated,” Krynick said. Also, they

used to exhibit at as many as 60 shows a year, but these

days they are down to a small fraction of that number.

Consequently, much will hinge on selling privately to

folks they’ve coaxed to visit them in North Egremont.

“It will be clients who know us,” Krynick said, to which

Nestor added, “We just want it to be friendly and casual.”

He noted that they’ve already had attention from people

who have visited their website.

Krynick handles the website, which is neat and clean,

but “we’re not good at maintaining.” Nestor puts a

positive spin on it. “We’re using it as a calling card. We

do Instagram but don’t work on it as hard as we should.”

For those readers whose memories go back quite a way,

we would point out that this church is a short distance

away from where dealer/artist John Sideli used to sell out

of his church on the other side of the road.

Since the church is essentially one large—2800 square

feet—space, stock and living quarters mingle together.

This may eventually have an effect on the couple’s

inventory. Nestor said, “Now anything we buy we’re

going to have to look at. I think it’s going to affect our

buying.”

As if knowing what to buy was not already hard enough

these days, “The market seems like only special quality

pieces sell at any price point,” Nestor said. “It either sells

so quickly—in a day—you’re amazed; otherwise it’s

still here a year later. A lot of stuff is just not desirable

anymore at any price.”

The couple’s new location should provide good access

to their natural clientele—New Yorkers. Nestor said that

their stock reflects a distinctively New York taste. Their

look isn’t necessarily meant to be cozy. It’s meant to have

an edge. He noted that even when he and Krynick were

doing dozens of shows a year, they always focused on the

New York market, picking venues that were either in the

city or were “wherever New Yorkers went on vacation.”

NorthEgremont fits the latter category. It’s in themiddle

of a large swath of geography where New Yorkers like to

spend their leisure time. It’s on the western edge of the

Berkshires; it’s no more than about an hour from much

of the Hudson valley as well as southern Vermont, and

it’s even closer to the hills of northwestern Connecticut.

When they were still doing many shows, the annual

summer show in Union, Maine, and Stella’s botanical

garden show in Chicago were the farthest afield they

ventured. But those locations were the exception; just

about everything else was centered on New York City.

As is the case with so many dealers, they retain a special

regard for Irene Stella. “We did every show she did at the

[New York City] armory,” Krynick said. “And earlier we

did four or five Stella piers a year.”

Nestor continued, “All the Stellas and Rhinebecks—

that was sort of our milieu, where our stuff fit in the

best.” He recalled the fevered buying at some Stella pier

shows. “When we first started doing the Pier Show, we

would sell like a hundred things. Then we’d go back the

next weekend with a different look.”

Today the shows they do number in the single digits.

Three of them are Brimfield. “We still love Brimfield,”

Nestor said. “There are still people who love antiques

who come, and we still find we do fine.” They are not

partial to a particular Brimfield venue. “We move

around,” Krynick said.

They also exhibit at two of Karen

DiSaia’s shows—her New York Botanical

Garden venue and the Collector’s Fair

during Antiques Week in New Hampshire.

They feel DiSaia has a knack for getting

charities seriously involved in her shows’

successes. Of the New York Botanical

Garden show, for example, Nestor said,

“It’s cool, with an active board. There’s

serious buying at the preview party.” He

said that DiSaia appears to be able to

convince preview-goers that they can’t

just show up for the hors d’oeuvres;

they’re supposed to buy stuff.

They like DiSaia’s Manchester show

because, Nestor said, “It’s like an old

home week for people who like antiques,”

even though as Krynick noted, “They act

like we’re not ‘really’ antiques.” And that

is after they “tighten it up” and edit out

some of their more adventurous purchases.

They are not fans of the old-line charity

shows that had long been the venues to

which dealers aspired. Nestor said, “All

“Now anything we buy we’re

going to have to look at. I think

it’s going to affect our buying.”

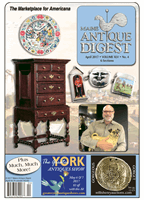

This Greta Garbo mask was made by a woman in

Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, Nestor said. He thinks her

name was Ruth Paige or Page. She made a group of

celebrity masks. Nestor and Krynick bought about half a

dozen of them, including Edward G. Robinson and Leslie

Howard. Nestor said Garbo is “the cream of the crop.”

The mask is life size and priced at $1000. The other celeb

masks are substantially less expensive.

Annie the dog—arguably the most irrepressible

member of the family.

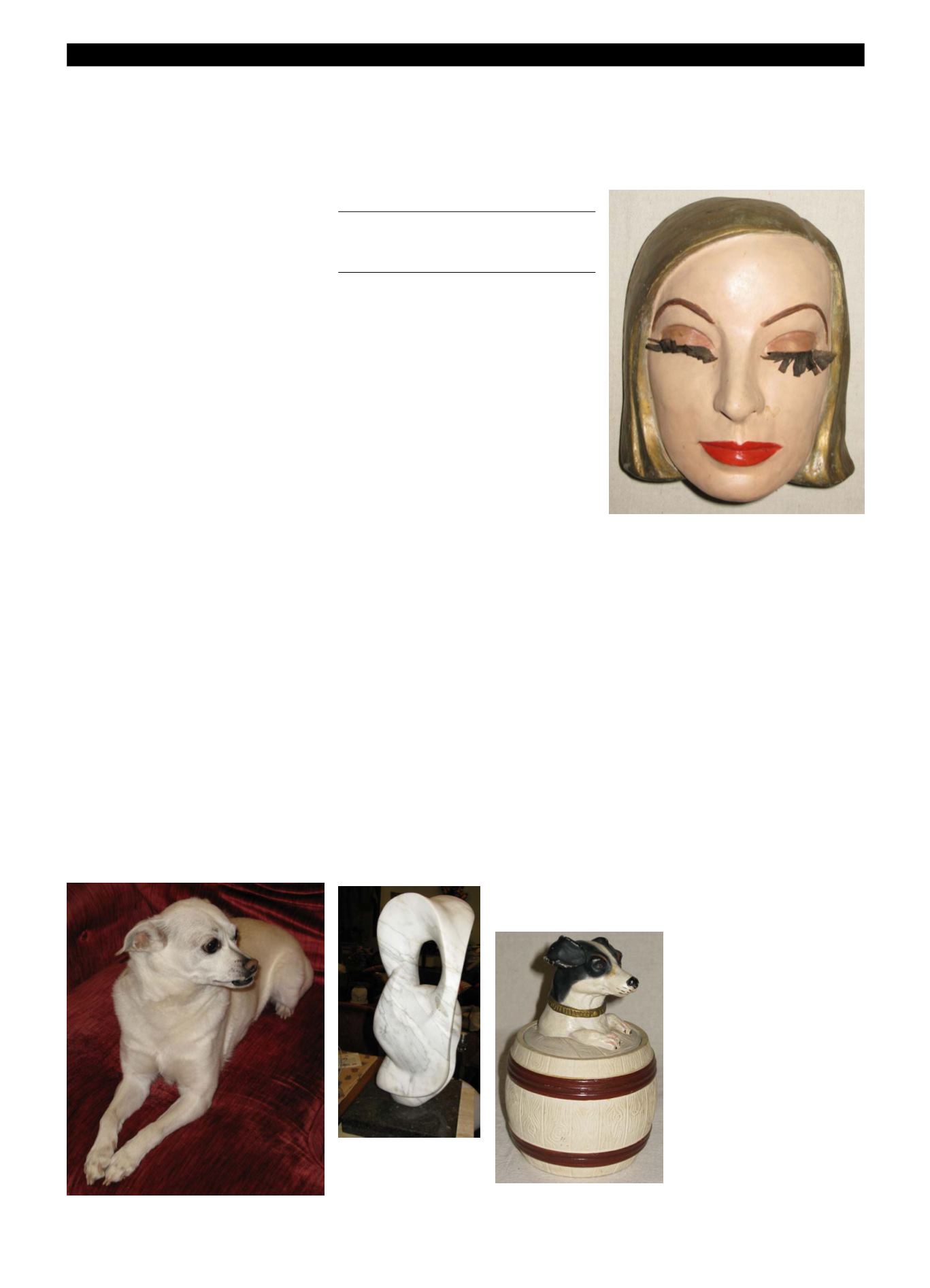

Unsigned 1960s marble

sculpture, 21" tall. Nestor said

a retired modern art dealer saw

it and said it was by Étienne

Hajdú (Hungarian/French,

1907-1996), but he’s selling it as

unattributed for $3800.

Pottery tobacco jar, $395. Nestor said,

“We don’t buy Victorian or pottery,

but we buy dogs.”