28-E Maine Antique Digest, April 2017

-

AUCTION -

28-E

Sotheby’s, New York City

The Iris Schwartz Collection of Silver

by Lita Solis-Cohen

Photos courtesy Sotheby’s

I

ris Schwartz got hooked on silver after

she saw the work of Hester Bateman

(1708-1794) and realized that a

woman ran a London silver workshop in

the middle of the 18th century. Schwartz

soon decided to specialize in American

silver. Over a period of 30 years,

encouraged by her husband, Seymour,

she amassed a collection that told the

whole story of American silver with

examples from Montreal to Alabama,

from New Jersey (where she lived) to

California, from the beginnings in Boston

(1660s) until the end of the 20th century.

The heirs of Iris Schwartz (1921-2011)

finally gave Sotheby’s permission to sell

her collection, which had been boxed up

since she moved to Atlanta to be with her

daughter at the end of her life.

There was something for every taste

at the auction on January 20. Schwartz

had bought silver by famous makers and

those less well known and collected an

enormous number of forms, including

apple corers, nutmeg graters, a bosun’s

whistle, an egg coddler, as well as

candlesticks, teapots, and bowls ranging in

size from a mammoth Martelé punch bowl

(it did not sell) to dollhouse-size Onslow

pattern flatware by William B. Meyers,

which brought $3750 (includes buyer’s

premium), well over its $1000/1500

estimate. A tankard made in Boston circa

1665 by Hull and Sanderson, America’s

first silversmiths, sold for $27,500. It was

estimated at $10,000/15,000 because its

top was made by J. H. Gebelein in the

20th century. A pitcher that Ubaldo Vitali

made in Maplewood, New Jersey, in 1988

sold for $11,250 (est. $3000/5000).

Schwartz bought at flea markets and

antiques shows but most often at auction.

Kevin Tierney, head of Sotheby’s silver

department during the entire time she was

collecting, was her advisor; Ubaldo Vitali

was her conservator. She loved the hunt

and bought so much that she could not

display it all. Her daughter, Barbara, who

came to the sale, said she has memories of

her mother and father drinking sparkling

water from their American silver beakers

made by Jacob Hurd in Boston circa

1733—and given to the Congregational

Church in South Byfield, Massachusetts.

Schwartz had bought the pair of beakers at

Christie’s in June 1982 for $39,600

(est.

$12,000/18,000).

Dealer

Jonathan Trace of Portsmouth, New

Hampshire, bought them at this sale

for $32,500 (est. $30,000/50,000).

Museums did some buying.

Bradley Brooks, curator of the

Bayou Bend Collection (a satellite of

the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston),

bought a Baldwin Gardiner silver

tureen on its stand, made for John

G. Coster, who was one of only

five millionaires in New York City

in 1830. The tureen is similar to an

example by the Royal Goldsmiths

Rundell, Bridge, and Rundell, which

demonstrates the sophistication of

American silversmiths in the 1830s.

David Barquist, curator of

American decorative arts at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art,

bought a very rare early mug made

by John Allen and John Edwards

of Boston, circa 1695, based on a

baluster ceramic form found in English

earthenware and delft, in turn from a

Chinese ceramic form. It sold for $25,000.

In June 1994 it had sold at Sotheby’s for

$63,000 (est. $10,000/15,000).

Colonial Williamsburg asked Tim Mar-

tin of S. J. Shrubsole, New York City, to

bid for a circa 1795 silver teapot by Asa

Blansett, who worked in Dumfries, Vir-

ginia, and he got it for the museum for

$43,750 (est. $5000/7000). In January

1994 it had sold at Christie’s for $16,100

(est. $4000/6000). This demonstrates how

silver made in the South is in great demand.

Stiles T. Colwill of Halcyon House

Antiques, Lutherville, Maryland (near

Baltimore), is a designer and collector

and has served as chair of the board of

trustees at the Baltimore Museum of

Art. He bought most of the Baltimore

silver offered. He paid $16,250 (est.

$5000/8000) for an 1830 silver pitcher

by Andrew Ellicott Warner of Baltimore,

which had sold at Christie’s in October

1989 for $8800 (est. $2000/2500). A large

circa 1805 coffeepot by Charles Louis

Boehme was his for $15,000. He said he

owns the rest of the tea set. At Sotheby’s

in 1993 the coffeepot sold for $23,000

(est. $7000/9000). Colwill spent $32,500

(est. $15,000/20,000) for a centerpiece

bowl by William Ball of Baltimore made

circa 1805 for Governor Charles Ridgely

of Hampton. (At Sotheby’s in June 1998,

Schwartz had bought it for $36,800.)

Colwill said it will go to the Baltimore

Museum of Art. Colwill paid slightly

more at $35,000 (almost three times its

high estimate) for a four-piece circa 1800

tea set by Charles Louis Boehme. Colwill

said he has been looking for a complete

Baltimore tea set with a tea caddy for 40

years.

Baltimore is below the Mason-Dixon

line. Present-day Delaware is just east of

the line. Three phone bidders competed

“I am happy to get a few

of my favorites back.”

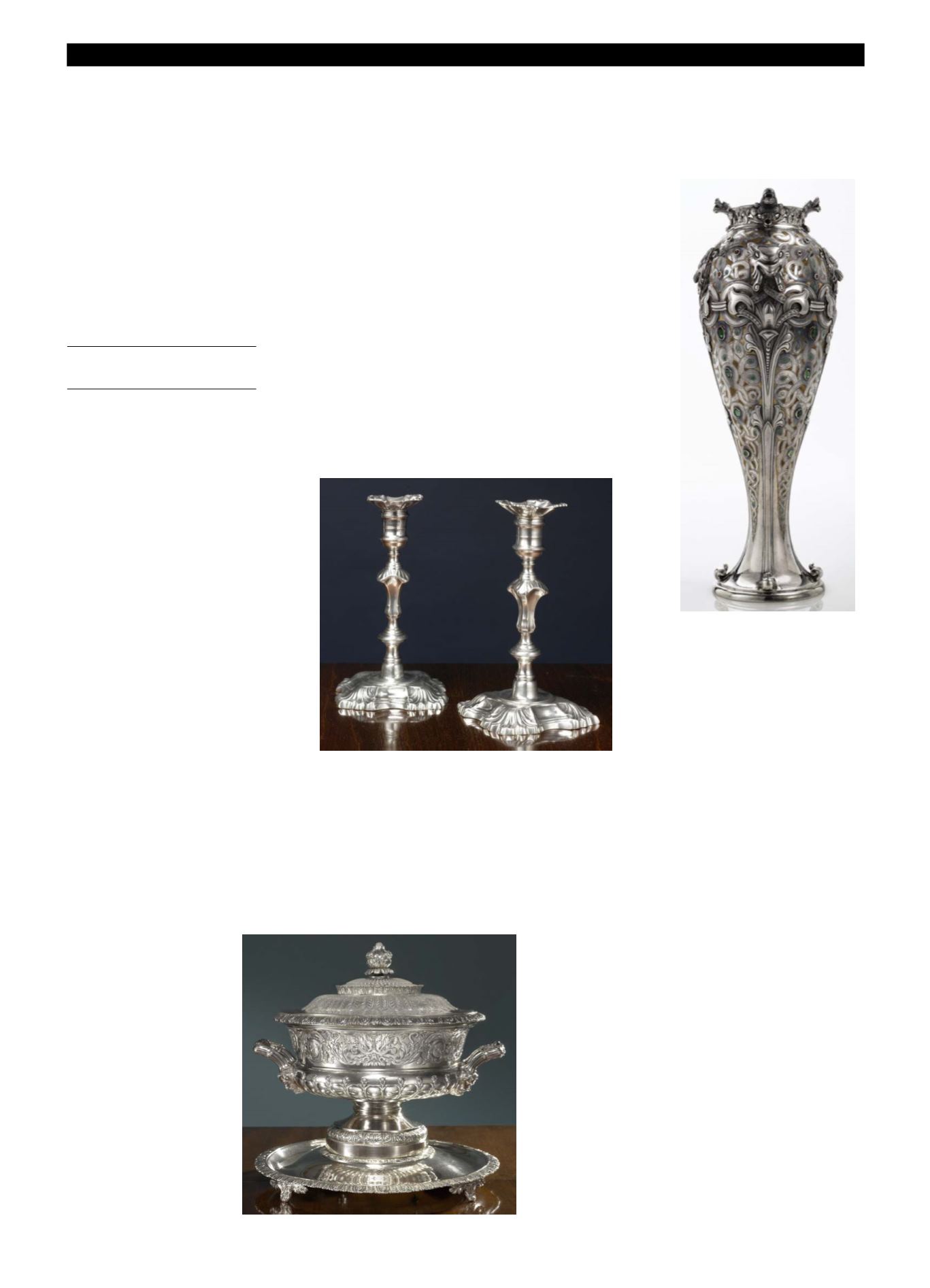

This Viking-style vase in silver, enamel,

and set gems was designed by Paulding

Farnham for Tiffany & Co., New York,

in 1901 for the Pan-American Exposition

in Buffalo, New York. The body is

embossed and chased with Celtic knots

and stylized fox masks on a colored

enamel ground, set with faceted citrines,

cabochon tourmalines, and peridots;

the pierced rim has applied toothy

dragon heads; and it is marked on the

base and numbered

14681-3674

inside

the base rim with the beaver mark for

the Buffalo Exposition. It is 12½" tall

and 30 oz. 14 dwt. gross and sold on the

phone for $175,000 (est. $20,000/30,000)

to a descendant of Paulding Farnham.

Paulding Farnham won gold medals at

the great fairs of 1893, 1900, and 1901.

The last proved to be his swan song, as

Louis Comfort Tiffany took control of

Tiffany & Co. the following year and

Farnham’s influence gradually declined.

This impressive tureen and cover on stand was made by Baldwin Gardiner

of New York, circa 1830. The diameter of the stand is 14½". The tureen is

circular with a lobed lower body spaced with flowers below a chased band of

scrolling foliage. The reeded loop handles centered by acanthus spring from

bearded masks. The stepped, domed cover has chased radiating palmettes

and a leaf-and-bud finial. It is engraved near the rim with a stag head crest.

Well engraved, the set sold for $87,500 (est. $80,000/120,000) to Bradley

Brooks, curator at Bayou Bend Collection, in the salesroom.

According to the catalog: “The arms are those of John G. Coster, one

of only five millionaires in New York in 1830. He joined with John Jacob

Astor, Robert Lenox, Stephen Whitney, and Nathaniel Prime at a time when

Cornelius Vanderbilt was a struggling ferryboat operator.”

“Baldwin Gardiner (1791-1869) was the younger brother of silversmith

Sidney Gardiner, of the firm Fletcher and Gardiner. Baldwin worked for

this partnership in their new Philadelphia retail shop until 1815, when he

established his own fancy hardware store. He partnered with his brother-

in-law Lewis Vernon from 1817 to 1826, then moved to New York to open

a household furnishings warehouse. Located at 149 Broadway, it carried

imported and more substantial goods than the Philadelphia shop. In addition

to home furnishings, Baldwin retailed special-order silver wares, the orders

often filled by Fletcher and Gardiner. Baldwin Gardiner’s career as a silver

manufacturer and retailer ended in 1848 when he moved again, to California.

“This tureen shows the ambition of wealthy Americans to live as well as

their English counterparts. The overall design is very similar to an example

by the Royal Goldsmiths Rundell, Bridge, and Rundell, with lobed body and

acanthus band, and the whole raised on a plateau

.”

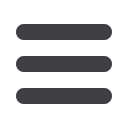

This pair of silver candlesticks is by Myer Myers of New York, 1750-65. Each of

the 8¼" tall sticks has stepped shaped square bases with shells at the corners, with

circular wells rising from knopped baluster stems with shells at the shoulders, and the

banded campana-form sconces are fitted with removable conforming shaped square

bobèches. Each is marked four times on its base. The pair sold for $150,000 (est.

$150,000/250,000). Iris Schwartz had bought the pair of sticks at auction in Baltimore

in 1997. They form a set of four with a pair in a private collection. David Barquist

suggests that the original owners of the four were Jacob LeRoy and his second

wife, Catherine Rutgers, who married in 1766. The sticks are first recorded in the

possession of their granddaughter Catherine Augusta McEvers. Sets of four American

candlesticks are rare. According to the catalog, only one other set of four candlesticks

by Myers is known, made for Catherine Livingston Lawrence and now divided

between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Art Gallery.