24-A Maine Antique Digest, December 2016

-

FEATURE -

24-A

We might be painting with too broad a

brush here, but you could probably say that

a Manhattan hedge-fund manager might be

more comfortable east of the Hudson, while

a Brooklyn hipster might find a place like

Andes more congenial. And now the region

draws its own group of celebrities. People

such as Kelsey Grammer, Amy Sedaris,

and

New Yorker

art critic Peter Schjeldahl

are regulars in the area. Sedaris has been a

Scherer houseguest.

This is quite a change from earlier when

Andes’s main claim to fame was the part it

played in the Anti-Rent wars of the 1830s

and ’40s. Violence erupted when vast tracts

of Delaware and Albany counties were still

owned in feudal fashion by the old “patroon”

oligarchy, and tenant farmers rebelled at

paying rapacious rents. In 1845 locals of

Andes dressed as Indians (why did white

rebels always try to blame everything on

Native Americans?) and shot dead the local

undersheriff who was trying to collect a $64

rent.

So there are now people who appreciate

what Scherer is trying to do. He said, “Most

of my clients are second homeowners from

the city—artists, writers, models, people in

the creative fields. Often buying from my

shop is their first antiques purchase.”

As if on cue, as we interviewed Scherer on

a quiet Thursday afternoon, a couple—she

with the tall good looks of a former model,

dressed in a 1970s denim jacket with patches,

and he looking equally urbane, bought an

old leather-bound tape measure. It’s the type

of item that a local farmer or carpenter might

value at $4 or $5. These folks were delighted

to pay $45.

Scherer, a highly trained painter who has

shown in New York City, said, “I decided to

make this the most interesting shop—like it

was in Paris or anywhere else. I do not dumb

it down. People underestimate people’s

desire to learn and enjoy beautiful things.”

He added, “Bricks and mortar [as opposed

to online business] is getting harder and

harder. You have to make it an experience

for people. There has to be a reason for them

to come in.” He completely “reinstalls” his

inventory every season so that it always

appears fresh.

Scherer doesn’t paint as much as he used

to. Instead, “I think of everything as my

artwork. My shop is all vignettes. It’s about

creating an atmosphere, not just throwing

stuff in and letting people rummage through.

There are lots of things I don’t buy that I

know there’s money in, but I know they

won’t fit. For me, it’s about the display.

That’s what you have to do today to keep an

audience.”

When it comes to antiques, Scherer said, “I

love the nineteenth century.” He especially

likes “things that are primitive and show their

use and wear.” He also feels these pieces can

fit well into modern interiors. “People don’t

think of the nineteenth century as modern,

but pieces with no extra frills [he pointed to

a simple country cupboard at this juncture]

could go perfectly well in a Tribeca loft.”

In fact, although he doesn’t carry much

mid-century modern, Scherer is not averse

to buying it. “If I see a 1950s driftwood

lamp that fits with my aesthetic, I’ll get it,

or a beautiful Danish modern credenza.”

His job “is to bridge the gap” for clients

who are not necessarily conversant with

antiques. “People up here are not looking for

pedigree.”

Neither is he. Scherer said, “I go into a

shop with all period stuff, and the pieces

kind of negate each other. It robs them of

energy.” This attitude may explain why, as

he said, “When old-timers come in, they say,

‘So, you really aren’t an antiques shop.’”

He tries to create an air of authenticity in

the shop, where new and oldmix comfortably

but retain their identities. In a world where

everything is knocked off—Scherer calls it

the “Restoration Hardware syndrome”—he

feels he gives customers an experience that

they might not easily find elsewhere.

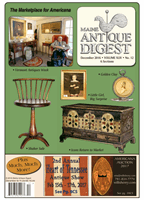

A 19th-century cupboard in old white, $850. “It’s

looking very modern,” Scherer said. The white milk-

glass apothecary bottles are vintage, $18 each. Above

them are copper luster pitchers in the $40 to $50

range. “They used to be for little old ladies, but now

people say, ‘What are those?’” Scherer said. Of the

ironstone above the copper luster, Scherer noted, “I

always have a good selection of ironstone platters,

usually in the sixty-dollar range.”

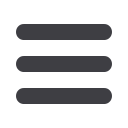

Vintage papier-mâché guest trays. If you grew up in the 1950s or ’60s, your

mother probably had some. They’re $12 each.

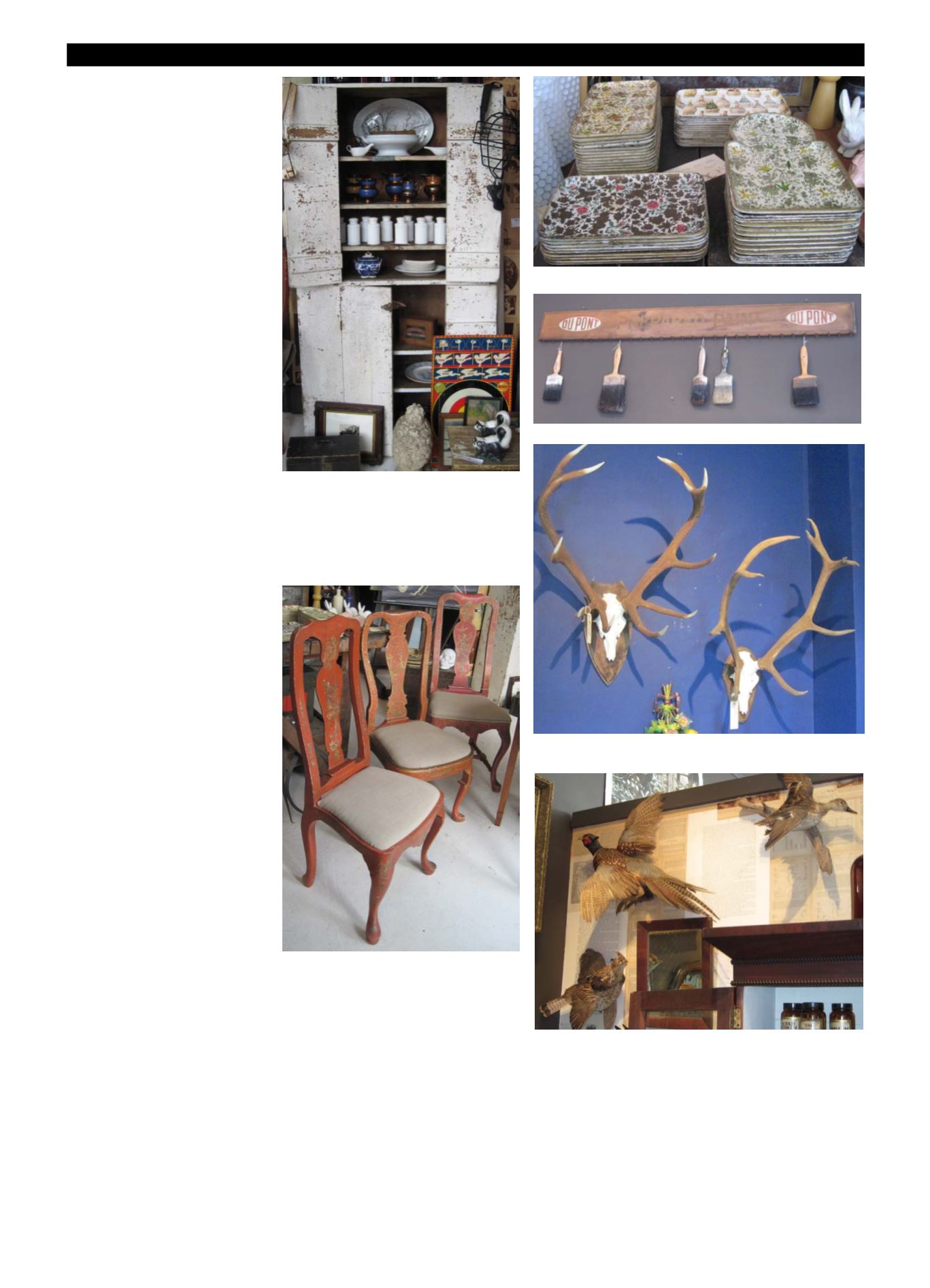

Three Queen Anne chairs in red and gold chinoiserie.

The chairs are all different but appear to have

substantial age, and the decoration on each is also

subtly but distinctly different. Other dealers might pass

on these because they don’t match, but that’s exactly

what Scherer likes about them. “They’re sculptures

found together,” he said, and he is asking $1800 for the

three.

For a couple of years Scherer also operated a

smaller version of Kabinett & Kammer in New York

City’s East Village. “I called it a pop-up shop. It was

small, and the lease was only for two years.” But

operating two places was a chore, and he shut the

city store when the lease was up. The best thing about

the city shop was “more access to more money.” He

pointed out that he was able to sell a taxidermy zebra

there for $7000. When he sold another one in Andes,

he got $4000. (Don’t worry, “Both died of natural

causes at a zoo,” he said.)

He said selling taxidermy accounts for “maybe ten

percent” of his business. “It ebbs and flows.”

Scherer supplements his shop income by teaching art history and

design two days a week at the SUNY Oneonta campus about 35 miles to

the northwest of Andes. He also does occasional design work and would

like to do more of it.

He said, “I spent three years doing Anderson Cooper’s firehouse

downtown [Manhattan], and I’m working on a bar here in Andes, right

across the street. We’re designing a tap room to be like an English

gentleman’s place.” He has also restored three 19th-century homes in the

area for clients. On those projects, “I’m like an art director.”

Scherer grew up in Miami. “My mother always used to go to flea

markets, Salvation Army, and antiques shops. I bought my first antique

when I was sixteen. It was a brass Art Deco clock,” he said, noting that

this was a relatively early piece for that area. “Remember, this was in

A paint-brush rack with brushes, $275.

Antlers. Scherer said they are natural sheds and that the “skulls” are actually

white-painted iron. The larger pair (on the left) is $395. The ones on the right

are $350.

Taxidermy duck, pheasant, and grouse in the $145 to $165 range.