Maine Antique Digest, April 2015 7-D

- FEaturE -

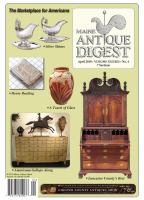

T

here are numerous other versions

of the portrait of the musician

Hendrik Liberti seen here—one of

the best known hanging in the Alte

Pinakothek in Munich and another

to be seen in one of the 365 rooms

of Knole House in Kent, for exam-

ple—but it seems quite likely that

this is the original version, painted

in Antwerp, circa 1628.

Once part the incomparable pic-

ture collection of King Charles I of

England, it was among the treasures

sold off by the Commonwealth fol-

lowing the king’s execution in 1649.

Listed in the inventory of Whitehall

Palace as a portrait of “ye singing

man,” it was at the time sold for

£23 to the London based painter and

agent Jan Baptist Gaspars. It passed

through a number of other noble col-

lections over the years and was last

seen at auction in the early 1920s,

when it was acquired by the grand-

father of the “lady of title” who sent

it for sale at Christie’s on December

2 last year.

Untouched, of sound provenance,

and a fine example of the portraiture

of Sir Anthony van Dyck, it was

described by Christie’s as having

“a poetic quality,” while a preview

piece in

The Art Newspaper

said it

was “one of the artist’s most lan-

guorously languid portraits, the sitter

depicted in a state of aesthetic rev-

erie, his eyes dreamily distracted.”

Perhaps so. He may indeed be think-

ing about a new composition, but

might he also be simply bored?

In 1676, the celebrated diarist

John Evelyn saw the portrait in the

London house of the 1st Earl of

Arlington and described it as “An

Eunuch singing.” Liberti did indeed

sing as a young man in the choir

of the cathedral in Antwerp, but he

found fame as a composer and spent

40 years of his life as the cathedral

organist.

In the early years of the last cen-

tury, American collectors were

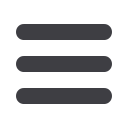

V

irtually forgotten for two centuries,

highly individual in his later still life

compositions and an artist about whom

very little is known, Adriaen Coorte

is now one of the most sought after of

all Dutch still life painters—a revival

ignited in the late 1950s by an exhibition

held at the Dordrechts Museum in the

Netherlands.

The little oil of three peaches and a

Red Admiral butterfly seen here, mea-

suring just 12¼" by 9¼" and executed on

paper laid down on a wooden panel*, was

sold to a European collector for a record

$5,391,020 at Sotheby’s on December 3,

2014. And what is more, it was making

an unexpected return to the London sales-

rooms just three years after having set an

earlier record in the London salesrooms—

something that does not usually bode well

for a picture’s chances.

In December 2011, having emerged

from a New Zealand collection that had

been its home since 1860, it had set a

record for the artist in selling for $3.216

million at Bonhams. I was convinced that

I had featured it in one of my London

selections at the time, and though I have

certainly had the odd Coorte in these

pages before, it seems that this was not

one of them—so I am pleased to

get this second chance.

Coorte’s carefully balanced

still life paintings, their delicate

colouring contrasted with dark

backgrounds and often setting the

produce on stone ledges, are, said

Sotheby’s, instantly recognisable

for their simplicity of treatment

and restricted range of subject

matter. The auctioneers also draw

comparisons with the highly indi-

vidual still life paintings of the

early Spanish painter Juan Sán-

chez Cotán (1560-1627).

But who was Coorte?

Thought to have been a native

of Middelburg in the watery

Dutch province of Zeeland, he

was active from 1683 to 1705.

The earlier of the 64 works now

accepted as genuine feature birds

and poultry and, say experts, are

sufficiently close in style to those

of Melchior d’Hondecoeter to sug-

gest that Coorte may have studied

with him in Amsterdam. The only

written record of Coorte, however,

is a mention in the yearbook of the

Painters Guild of St. Luke in Mid-

delburg, one that criticises him for

selling works independently of the

guild.

It has been suggested that he

was an amateur, or artist of inde-

pendent means, and the fact that

his paintings show little obvious

influence by the work of other art-

ists, and that Coorte exerted little if any

influence on others, this notion of a gen-

tleman artist following his own singular

artistic path has a certain appeal.

Asparagus, wild strawberries, peaches,

medlars, apricots, black and red currants,

cherries, gooseberries, and grapes, along

with nuts and shells, are Coorte’s sub-

ject matter, their combinations perhaps

influenced by seasonal availability. One

of Coorte’s asparagus pictures, sold for

$3.58 million by Christie’s in July 2012,

was featured in that year’s October issue

of

M.A.D.

*

It seems that from the mid-1690s

onwards, many of Coorte’s paintings were

painted on paper laid down on canvas, or,

as here, on panel. Coorte drew his basic

design on paper first, and then worked in

oils on top, a technique that is certainly

unusual in the 17th and 18th centuries

and may very well have been personal to

him. A similar study of two peaches and

a fritillary butterfly, which sold at Sothe-

by’s in 2006 for $922,130, was shown

during restoration to have been painted

over a page from the account book of a

merchant who was trading in the Baltic

port of Gdansk (Danzig) in the 1600s!

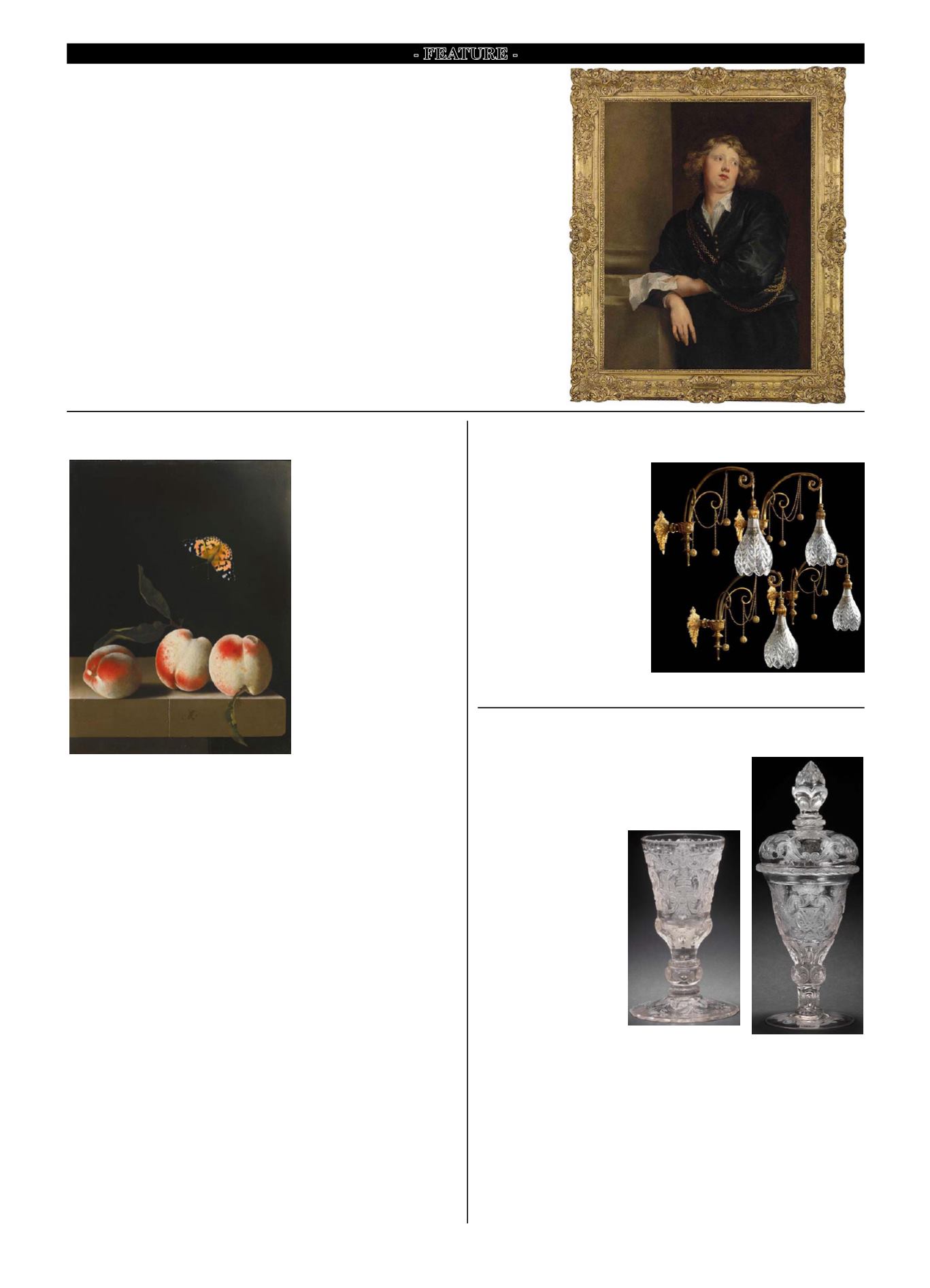

E

stablished in 1807 in Birming-

ham, the firm of F. & C. Osler

was a principal manufacturer

of light fittings and glass furniture.

Osler also had a London showroom

that helped underpin their reputation

as market leaders and as a busi-

ness with a reputation for quality

workmanship. There was an inter-

national, or at least British Empire

side to the firm as well, notably

with goods exported to the Indian

subcontinent, and in Calcutta, Osler

shared a showroom with the silver-

smiths, Hamilton & Co.

The set for four Victorian

gilt-bronze wall lights by Osler

seen here, the cut-glass shades

of inverted tulip form, sold for

$11,735 at Bonhams on November

19 last year.

F

ive lots from the Klaus Biemann collection of fine Ger-

man glass, sold by Bonhams on November 26, 2014,

are the focus of this piece.

Born and educated in Austria, Professor Klaus Biemann

obtained his Ph.D. in organic chemistry in Innsbrück in

1951, but four years later accepted a research post at MIT,

moved to America and stayed

there until, having earned

many honours and even been

involved in NASA’s Viking

Mission to search for organic

compounds on Mars, he took

retirement in 1996.

Just three years earlier,

whilst attending an organic

chemistry conference in his

native Austria, he had met by

chance a distant cousin and

learned from him that they

were both great-great-great-

nephews to a famous 19th-cen-

tury glass engraver, Dominik

Biemann. A retirement hobby

beckoned.

Suitably inspired, Klaus

purchased his first goblet and

Singing, Composing or Just a Little Bored?

Sir Anthony van Dyck’s

three-quarter portrait of the

Flemish composer and organist

Hendrik Liberti (circa 1600-

1669), sold for $4.52 million by

Christie’s.

hugely enthusiastic buyers of

van Dyck portraits, but are

they still? All Christie’s would

say about the $4,522,645 bid

that secured this portrait was

that it came on the telephone.

However, in a

New York Times

report, a former

Antiques

Trade Gazette

colleague of

mine, Scott Reyburn, reported

that “the buyer was identi-

fied by dealers [whom he said

remained resolutely sitting on

their hands] as the British busi-

nessman James Stunt, who also

buys contemporary abstracts

by Oscar Murillo and Lucien

Smith.”

When offered by Bonhams in December 2011, this

still life of peaches and a Red Admiral butterfly by

Adriaen Coorte (c. 1660-after 1707) was acquired

by Noortman Master Paintings for a Dutch collec-

tor at what was then a record $3.216 million. Three

years on, and this time at Sotheby’s, it was once

more put up for sale and while many pictures mak-

ing rapid returns to the salesrooms suffer a loss,

Coorte’s little peaches did even better than before

and upped the record for his work to $5.39 million.

A Peach of a Still Life Ripens Once More into a

Record Breaker

Osler—Supplier of Light Fittings throughout the

Empire

A Crizzling We Will Go—Professor Biemann’s

Glasses

Friedrich Winter is a big name in this field, but while two examples of his work racked up

the highest bids, two others failed to sell—though this may have been a case of too many

riches in one go. The first Bonhams price list that I saw, issued immediately after the sale,

suggested that the 14¼" high goblet seen at right, deeply carved in the late 17th century

in

Hochschnitt

, or high relief, had failed to sell on an estimate of around $190,000/280,000.

But it subsequently emerged as the sale leader at $192,785, so presumably a post-sale deal

was agreed.

Decoration includes the cypher of Count JohannAnton von Schaffgotsch, whose family

had in 1687 granted Winter a special privilege to set up a water-powered glass cutting

works in Hermsdorf. In 1999, as part of the Otto Dettmers collection and at a time when

this market was rather stronger, it had sold for $176,520.

Sold for $54,080 at Bonhams was the Silesian goblet by Winter seen at left, another

piece produced in Hermsdorf, circa 1700, for his principal patrons. Just over 7½" tall, it

displays the von Schaffgotsch arms, incorporating a fir tree and the French motto

Aucun

temps ne le Change

(Untouched by Time).

☞