Maine Antique Digest, April 2015 15-C

- feature -

T

he July 2014 issue of

Maine Antique Digest

included an

article covering the April 8 Americana sale at Swann Gal-

leries in New York City.

1

Among the lots discussed and

reproduced was a remarkable collection of art and archival mate-

rial from the estate of artist Henry Grant Plumb (1847-1930).

The importance of the collection, estimated at $3000/4000, was

recognized, spurring bidding to $16,250. By fortuitous circum-

stances, I was able to acquire the collection from the winning

bidder, dealer James Olinkiewicz.

Olinkiewicz is a regular exhibitor at the Allentown, Pennsylva-

nia, paper show, and it was there that I stumbled upon the Plumb

material. For more than a decade, I have attended the show, pre-

sented three times a year at our local fairgrounds, and while I have

found many art objects and

related books and documents

there, none of my purchases

approach the Plumb collection

in size, scope, or importance.

Although I have 30 years of

practical and academic experience in the field of American art,

with a market orientation shaped by my experience as executive

assistant to one of the foremost American art dealers, such an

opportunity had never presented itself.

Like many ardent hunter-gatherers, I have heard stories of art-

ists’ estates turning up on the market, but I always figured that

it would take a fortune to be a player on that scale. That would

doubtless hold true for more prominent artists, but it was pre-

cisely the fact that Plumb had fallen into obscurity that put the

collection within reach.

2

Despite a rather encyclopedic knowledge of American art, I had

never heard of Henry Grant Plumb. My first move before commit-

ting to buy was a quick dip into my iPad Mini to consult key Web

sites. The search yielded no listings for representation in museums

or private collections in the Smithsonian’s inventories of American

painting and sculpture and only a meager record on AskArt.com.

3

My instinct told me that, despite this faint footprint, the collec-

tion, consisting of art and archival portions, was important. My

judgment was affirmed when I found out later that Plumb was

quite successful in his day. He sold to major collectors including

Thomas B. Clarke and the Havemeyer family. Furthermore, he

exhibited a number of times at highly competitive venues includ-

ing the National Academy of Design, the American Watercolor

Society, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He was

a longstanding member of the well-known Salmagundi Club in

New York City, participating in its exhibitions, social events, and

popular library mug auctions. In fact, the club owns two mugs

designed by Plumb.

4

Although I had zero cash flow at that moment, I promised

Olinkiewicz that I would get the requisite sum to him within a

few weeks.

5

Since we had done business before, and he did not

want to haul six heavy boxes back to his home on Long Island,

New York, a drive of several hours, he handed over the treasure.

A sense of excitement and determination flooded my brain at the

same time that a feeling of responsibility to do the right thing

set in.

Working late into the night, fueled by adrenalin, I made a

first pass at the boxes, which had already been roughly sorted. I

quickly realized that not only was there a significant number of

artworks, ranging from the artist’s childhood sketches to mature

drawings, watercolors, and oils plus three sketchbooks, but that

the archival portion was outstanding.

Plumb was an inveterate recordkeeper with incredibly legible

handwriting. He had many of his paintings professionally photo-

graphed. Dozens of cabinet-card format photographs record his

paintings in watercolor and oil, each with the title and in many

cases the place of exhibition and name of the buyer written on

the back. Some of the photos depict works in the current collec-

tion, but many more are of unlocated pieces, providing a grasp

of the scope and size of his oeuvre. During the 1880s and 1890s,

Plumb painted a number of pictures of mice and some of cats,

most humorous but some ominous.

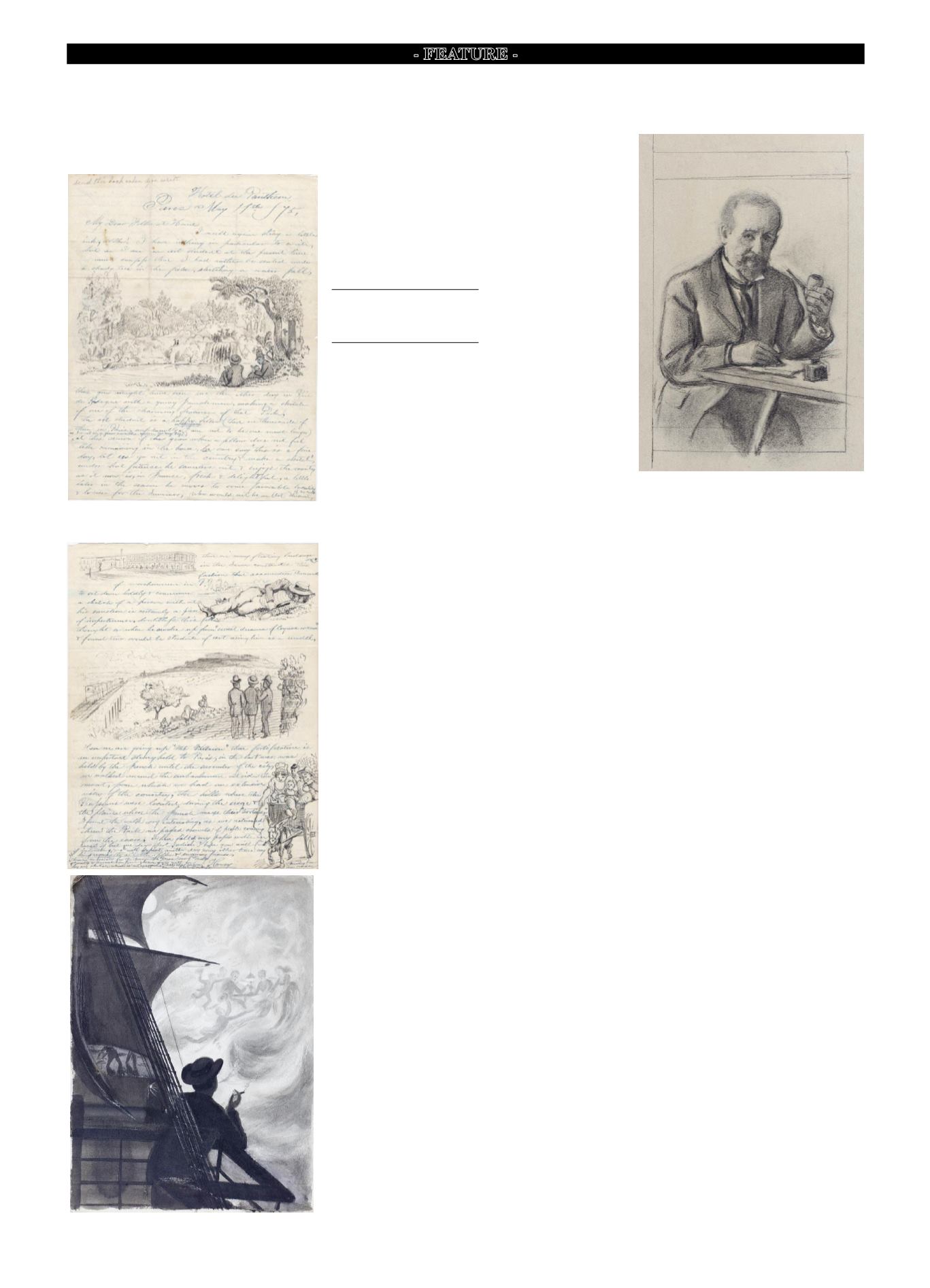

6

His rural childhood home in Sherburne, located in central New

York, inspired a number of images of farm animals, and several

paintings feature his young son and daughter and his wife. Apho-

tograph of Plumb, which had been featured in the trade publica-

tion the

Quarterly Illustrator

, along with the existence of a num-

ber of paintings and drawings carried out in grisaille (the range

of grays, blacks, and whites used by artists in the golden age of

illustration) demonstrate that he pursued illustration for a portion

of his career. After 1900, he increasingly painted landscapes and

depicted serene pastoral themes near his family home and sum-

mer residence in Sherburne and other places in the Adirondacks.

He also was a very capable portraitist. The collection includes a

pastel portrait of his wife and an oil portrait of a Breton peasant

woman.

7

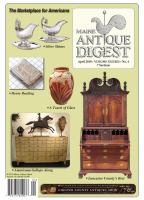

An entire carton was filled with scores of letters Plumb wrote

to his family from the time he left home in the 1860s through

the 1890s, chronicling his daily life.

8

Immediately obvious as an

important source are the several dozen letters he wrote during

his four years in Europe, 1874-78, when he studied art at the

renowned École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Plumb was one of the

few foreign artists to gain admittance as a fully matriculated

student. The entrance exams or

concours des places

were noto-

riously difficult. Lasting many hours, with questions asked in

French, they tested applicants in anatomy, perspective, world

history, and ornamental design. About one in three applicants

Rediscovery: Henry Grant Plumb, Master of Arts

and Letters

by Christine Oaklander

passed muster. The better the combined final

score, the better the student’s classroom position

in relation to the model.

Once admitted, Plumb entered the ateliers of

internationally famous Orientalist painter/sculp-

tor Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), instructor of

painting, and the military painter Adolphe Yvon

(1817-1893), instructor of drawing.

9

Plumb also

worked in the independent atelier of Carolus-Du-

ran (1837-1917), where he encountered Theodore

Robinson (1852-1896), who is appreciated today

as one of the foremost American Impressionists.

Plumb’s letters not only describe his experi-

ences living and studying in Paris, but they also

visually chronicle the classroom, artists’ lives

outside of the school, Paris street life, and his

wanderings throughout France, Switzerland, and

Italy, with dozens of tiny, beautifully rendered

pen and ink vignettes embedded in the text. Full

of life, these demonstrate the artist’s humanity

and sense of humor.

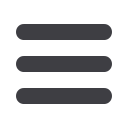

Plumb also recorded his European adventures

in a series of watercolors in grisaille and full

color. For instance, he created depictions of the

Luxembourg Gardens, a classroom at the

école

,

and one of himself smoking while leaning against

the rail of a ship with dreams of his family at

home and his future adventures floating in the

smoke plumes overhead.

10

A large grisaille water-

color from the Paris period,

Preparing the Punch:

Latin Quarter Sketch Club

,

captures a convivial

artists’ gathering. Habitués of this club, founded

in 1873, included fellow Americans J. Alden

Weir, John Singer Sargent, Douglas Volk, J. Scott

Hartley, and George Inness Jr.

The largest of the six boxes contained the art-

ist’s portfolio and an assortment of framed pic-

tures, most of them oils ranging widely in date,

subject, and size. Several oils were completed in

France, including a small figure painting rendered

in an Orientalist style, probably painted under the

influence of his teacher Gérôme. Another paint-

ing, completed after Plumb returned to New York

City from Europe, is a sweetly sentimental image

of a small black child asleep in bed with a partly

eaten biscuit fallen on the covers.

11

Hovering in

the background is a tiny mouse with a gleam in

its eye, gathering up courage to snatch the biscuit.

Plumb turned this painting into an engraving with

a slight alteration, enlarging the mouse and mov-

ing it to the foreground. The accuracy, liveliness,

and immediacy of the scene invite our presence;

we can almost sense the mouse’s whiskers quiver-

ing. Rounding out the group associated with this

charming genre scene is the original copper plate,

in pristine condition.

Pickaninny

is one of several paintings that

Plumb turned into prints and copyrighted, pre-

sumably as an additional source of income.

12

In

fact, the artist’s early career was spent as a drafts-

man and printmaker. He served an apprenticeship

in the 1860s in New York City under George W.

Hatch (1805-1867) , who headed one of the coun-

try’s leading firms for engraving and printing

Henry Grant Plumb to his family, Paris, May 11, 1875.

The vignette on the first page shows the artist and a friend

sketching in the Bois de Boulogne.

Untitled, watercolor on paper, circa 1874, 14" x 10".

Henry Grant Plumb self-portrait, circa 1910.

I had never

heard of Henry

Grant Plumb.

☞