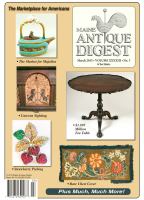

Maine Antique Digest, March 2015 11-C

- FEATURE -

proceeded even during Washington’s extended

years away as general and president. Histo-

rians and restorers have benefited from those

absences because Washington directed much

of the work by communications from afar, and

those letters still exist. We know that he had

English pattern books, access to drawings and

objects from his English and French friends

including Lafayette, and advice from deal-

ers who furnished his presidential quarters in

New York and Philadelphia. The New Room,

the place where Washington’s body was laid

out after his death, is freshly restored follow-

ing extensive research and analysis. Today’s

visitors can become steeped in its Neoclassical

symmetry, architecture, furniture, and artwork.

David Bosse, Historic Deerfield’s librarian

and curator of maps, focused his presentation

on the paper maps of the post-Revolution years.

Earlier engraved copper-plate maps, mostly

printed in England for government and private

subscribers, had ornate cartouches and flour-

ishes. These were succeeded by plainer, more

accurate ones proudly labeled as produced in

America. Some maps even placed the prime

meridian at Philadelphia rather than London.

While most mapmakers were not financially

successful and many freely copied their com-

petitors’ work, their maps and town plans had

important commercial uses and also were dis-

played as “ornamental furniture” to indicate the

owners’ taste and learning. A few were origi-

nally tinted, but most probably were hand col-

ored later to enhance their appeal.

Zea returned to the podium to speak about

the Asa Stebbins clock, recently purchased

at Sotheby’s and returned to its first home

in Historic Deerfield’s 1799 brick Stebbins

house. Zea described the 1799 Aaron Willard

long-case eight-day clock as “fabulous,” as

“free-standing architecture,” and its mahogany

105" tall case he attributed to cabinetmaker Ste-

phen Badlam. It cost at least $100 new, when an

average worker’s daily wage was 25¢ to 50¢,

and it was a “planned acquisition,” designed to

display Stebbins’s affluence and sophistication.

Although far from Boston and one of the area’s

original settlers, Stebbins was far from being

provincial. He grew wealthy from agricultural

and industrial pursuits, and his home and fur-

nishings, all in the latest Neoclassical style,

confirmed his status.

An expert on early American clocks, Zea also

offered details on Aaron’s brother Simon Wil-

lard, a “genius” who could “package beauty.”

Simon’s invention, the patent timepiece known

better as the banjo clock, “denied wood” and

“was all about paint and glass.” Stebbins’s

Aaron Willard clock is a rare example of a

return of a cultural artifact to its original loca-

tion, regaining its place as the “heartbeat of the

household.” Any uncertainty about whether

this truly is Stebbins’s clock was resolved (not

only by documents and trails of ownership) as

the restored clock was eased into its corner.

When the installers began to secure the case to

the wall through a preexisting hole in its back-

board, they drilled into a filled hole in the house

wall—at exactly that spot.

Saturday’s final presentation was a demon-

stration by cabinetmaker Allan Breed of Roll-

insford, New Hampshire. Breed is the rare type

of fine craftsman who also lectures, writes, and

prepares exhibits on furniture restoration and

connoisseurship. He demonstrated his carving

techniques on a large mahogany bedpost, mate

to one he produced some years ago for the Pea-

body Essex Museum. He noted that this type

of carving “in the round” is easier (his word)

than carving “in the flat” when the wood grain

is more difficult to manage.

Breed also told us that early carvers had the

advantage of working with air-dried wood,

which retained a “buttery” feel not found in

modern drier kiln-dried lumber. A close video

camera allowed us to watch his hands and tools

on a large screen, and we saw leaves quickly

take shape on the curved red surfaces. Time

was money in the past too, and carvers needed

to proceed efficiently with a minimum number

of tools and tool changes, as well as work ambi-

dextrously as Breed does. Copying and creating

carved designs requires careful advance plan-

ning, and his voice of experience also warned

against designing a pattern for which no tool is

handy. While carving, both hands hold the tool,

one acting as the gas pedal, the other as the

brake. His tools are very sharp, but he warned

that cuts usually happen only when brushing

away wood chips. Finally, we learned that each

carver has a distinctive style, and an experienced eye can

learn to identify a carver in the same way that a musician’s

style is recognizable to music scholars.

Sunday’s opening presentation was the cure for anyone’s

morning drowsiness. William Hosley presented a high-energy

lecture, “Reflections onAsher Benjamin and Neoclassicism in

Early New England.” An independent and published scholar

who heads Terra Firma Northeast, Hosley is also well known

for his past work at the New Haven Museum, Connecticut

Landmarks, and the Wadsworth Atheneum. He is an expert

on “heritage tourism” focusing on smaller, lesser-known his-

toric sites. He admitted that he is particularly interested in

the second of the “two New Englands,” the inland and more

western-looking areas rather than the seacoast communities.

Prior to the American Revolution, architects were little

known and buildings were designed and built by carpenters,

joiners, and housewrights. Following our independence,

architects such as Asher Benjamin, designer of the original

building of Deerfield Academy, trained with pattern books of

Classical images and then designed buildings that reflected

our new “cultural nationalism.” Throughout western Mas-

sachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont, Hosley has doc-

umented and photographed hundreds of homes and public

buildings in what he calls the “Country Palladian” style. Per-

haps most important, Asher Benjamin published in 1797 the

first American builder’s guide, applying the Classical princi-

ples of mathematics, geometry, and science to architecture.

By 1802, he had arrived in Boston, become a “society hill”

builder, and never looked back. As Hosley quipped, Benjamin

became “the Martha Stewart” of architecture, producing 42

editions of seven books on the subject.

Hosley then moved onto the broader subject of American

Neoclassicism, a term that was not applied to the concept

until later in the 19th century. He stated that it reflected the

character and aspirations of the self-conscious post-Revolu-

tion generation. George Washington iconography, schoolgirl

needlework, printed engravings, symbolic eagle carvings

and inlay, and mourning pictures all demonstrated a hope

that our nation was heir to elevated Greek and Roman ideals.

New furniture forms and versions—sideboards, washstands,

desk-and-bookcases, and standing clocks—proliferated in a

“flaunting of geometry, symmetry, and complexity,” as did

gravestones. He called our New England meetinghouses “the

greatest things in our world” and wondered if “maybe Amer-

ica peaked during this period.”

Another well-known craftsman/scholar, Robert Mussey,

was next with “From Ancient Greece to the Streets of Bos-

ton: Furniture-Making in Urban Massachusetts.” Mussey

is a published expert on John and Thomas Seymour and is

now deep into a similar project on Boston cabinetmaker Isaac

Vose. Greek and Latin in this period were much more famil-

iar than today in Boston, and Classical iconography also was

well understood. Neoclassical-style desks, for example, were

“pieces of architecture,” geometric Latin and Greek languages

in three dimensions. Conversely, the Seymours are famous for

complicated veneers and inlays that reduce three dimensions

to two by the use of sand-scorched shadowing, “niche” and

“panel” inlays, and other optical devices that convey depth

and relief in place of deep carving.

Mussey cited many furniture objects in museum collec-

tions that incorporate Classical symbols and shapes—lyres,

swags, garlands, urns, goddesses, chariots, etc. He explained

that there really are three overlapping stylistic periods within

American Neoclassicism: Federal, 1785-1820; English

Regency, 1808-25; and Classical, 1813-40. The Grecian

style emerged in this third period, largely driven by Napo-

leon’s French Empire designers. Greek Revival motifs were

prevalent, especially favored by Boston’s extremely wealthy

merchant Peter Chardon Brooks, then faded as America

retreated from Classicism into the individualism and roman-

ticism championed by Emerson.

The appropriate finale was “It’s All Greek to Me: Pre-

serving the Captain Howland House,” presented by Ste-

phen Fletcher of Skinner, Inc. Lost on a house call drive to

Westport, Massachusetts, he passed by this unoccupied 1830

stone house languishing and deteriorating in that town. Fol-

lowing a two-and-a-half-year total restoration that included

demolition of an offensive addition and several dog kennels,

the home now stands in its Neoclassical splendor. Passers-by

continually ask “What was that,” guessing that it was a bank

or even a mortuary, proving that our culture today still asso-

ciates that ancient style with enduring institutions.

There was a bonus postscript for a small number of us

who stayed for J. Peter Spang’s guided tour of the spe-

cial collections room, named in his honor, in the Henry N.

Flynt Library. Spang, who “really likes Palladio,” has been

an active supporter of Historic Deerfield for more than 50

years, and his extensive collection of early architectural and

furniture pattern books is filling the room’s newly installed

shelves and cabinets. Several of his books, including clas-

sics by Sheraton, Hepplewhite, William Pain, James Gibbs,

and others, were laid out for us to peruse, and with clean

hands we turned pages. Spang pointed out his first important

book purchase of 1957, when he learned that such volumes

could actually be bought and owned, not just viewed in rare-

book libraries. For $8 at Goodspeed’s bookshop in Boston,

he bought a 1747 copy of James Gibbs’s

Bibliotheca Rad-

cliviana

, and later found additional volumes of it for even

less money while he was studying in London. His continuing

purchases over the next five decades now enable scholars to

study the books that guided the rise of Neoclassicism in the

new United States of America.

For more information and to learn about the dates and

theme of this year’s Historic Deerfield Decorative Arts

Forum, visit

(www.historic-deerfield.org).

David Bosse is librarian and curator

of maps at Historic Deerfield. Ameri-

can-produced maps of the new republic

appeared quickly after the American

Revolution. The first with an American

flag was in 1783, although it was printed

in England.

Philip Zea, president of Historic Deerfield,

welcomed us all, introduced a few speak-

ers, and delivered his own presentation on

the Asa Stebbins clock, which was recently

returned to its original Deerfield home.

Thomas Sheraton’s 1793 book is in Peter

Spang’s extensive collection of pattern

books that greatly influenced American

Neoclassical furniture makers.

J. Peter Spang, a Historic Deer-

field trustee, is shown examining

a volume on display in the library

named in his honor.

☞