10-C Maine Antique Digest, March 2015

- FEATURE -

AmericanNeoclassicism—JeffersonversusEmerson

by Bob Frishman

W

hen Ralph Waldo Emerson addressed Harvard’s Phi Beta

Kappa Society in August 1837, he declared that it was time for

our nation’s culture to declare independence from European

influences. In “The American Scholar,” he rejected Federalist and Neo-

classical principles embraced by post-Revolution leaders who viewed

the new nation as a reincarnation of ancient Athens and Rome. While

thousands of American public buildings continue to look like Greek

temples, hundreds of thousands of American private homes feature

pillars and pediments, and uncounted numbers of American furniture

pieces incorporate carved columns, swags, leaves, and urns, by 1840 the

country was turning away from Classical ideals and developing fresh

American styles and philosophies.

On the weekend of November 14-16, 2014, I was one of 80 partic-

ipants in Deerfield, Massachusetts, at Historic Deerfield’s 2014 Dec-

orative Arts Forum. The 2014 theme and forum title was “Borrowing

from Antiquity to Design a New Republic: Neoclassicism in America.”

Well-known curators, collectors, and restorers were speakers and were

in the audience, and all contributed to better understandings of the roots

and consequences of Classical influences on our nation’s founding gen-

eration. Skinner auctioneers and appraisers and Thomas Schwenke of

Woodbury, Connecticut, a longtime American Federal furniture expert

and dealer, sponsored the event.

Some of us arrived early on Friday afternoon for optional workshops

prior to the opening reception, and I chose “Inspired by Pompeii: Neo-

classical Ceramics for the American Home,” presented by Amanda

Lange, curatorial department director of Historic Deerfield. Seated

around a padded table in the backstage Esleek Room of the Flynt Cen-

ter of Early American Life, a small group of us was shown and could

handle ceramics in the Neoclassical style. With their restrained and

symmetrical ornamentation, these candlesticks, teapots, urns, and plates

were strikingly different from their Rococo predecessors encrusted with

frivolous decorations. As in several subsequent presentations, we were

reminded that the discovery in the early 1700s of Herculaneum and

then the 1748 unearthing of Pompeii triggered a major Western cultural

revival of interest in Classical design. English potters were inspired by

books illustrating the designs of ancient Roman styles, especially the

four-volume set published by Sir William Hamilton, and their wares

began arriving in America later in the 18th century. Even more ceramics

landed here following the return of the

Empress of China

in 1785 from

the first American shopping spree in Canton, opening the floodgates of

Chinese porcelain (and tea) into our ports.

That evening, in the Deerfield Community Center, where we heard

all subsequent lectures, Philip Zea, president of Historic Deerfield, for-

mally welcomed us. Zea then introduced our lead-off speaker, Wendy

Cooper, recently retired from Winterthur Museum. Most readers will

know something of her lifetime work as a foremost scholar, curator,

and author on American decorative arts. Accompanying her lecture,

“From Vase Backs to Swag Backs: Classical Furniture in New England,

1785-1825,” were many projected images of ancient art and architec-

ture, some taken during her recent visit to Sicily. These were followed

by examples of those designs applied to Paul Revere silver, Seymour

tables and desks, and iconic Federal furniture from the Kaufman collec-

tion of American furniture at the National Gallery of Art. The donation

of this premier collection provides Washington, D.C., museum-goers

with examples otherwise not available, unless they have access to the

State Department or White House. George Kaufman is deceased, but his

widow, Linda, was with us during the weekend.

The next morning, Gordon S. Wood presented “The Revolutionary

Origins of American Culture.” Wood, a Brown University emeritus

professor of history, is the author of prize-winning books and import-

ant articles on the American Revolutionary period. He noted that many

contemporary historians share Emerson’s conviction that our Revolu-

tion-era leaders were too imitative of and dependent on European cul-

tural influences, but he disagrees. Professor Wood believes that while

Jefferson and his peers embraced those principles, they sought to enlarge

and enhance the ideals to apply to all people, not just to elites and roy-

alty. Jefferson spent five years in Europe representing his homeland and

on his return believed that art would transform culture, not just serve

as entertainment for the rich, and would provide moral and educational

inspiration to an enlightened citizenry.

Diplomatic ministers and consuls based in Europe after the Revolu-

tionary War imbibed Classical aesthetics and returned home with the

ideals, fashions, and artifacts. Artists, such as John Trumbull and Ralph

Earl, became known as teachers and philosophers advancing truth,

beauty, and virtue, not just as handwork artisans. They offered histori-

cal portraits and a painted record of our Revolution, reminding viewers

of its aspirations and protagonists. Prints and engravings, periodicals,

exhibits, salons, and concert halls all brought refinement and culture to

the rapidly expanding American middle class. Washington, D.C., rose

from swampland to be the new Athens or Rome, its public buildings

recalling the Parthenon, its Goose Creek renamed the Tiber.

By 1840, however, the country had turned away from the Federalists

and their high-minded moralizing, and most Federalist gentlemen grew

disillusioned by the advance of Jacksonian democracy. Fortunately for

later generations, many of them turned from public office to private

philanthropy, and their lasting contributions include the Boston Athe-

naeum and the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. Their

influence remains far more than as a lingering homage to old European

values.

George Washington, often pictured in togas and classic poses, is cer-

tainly the most iconic of our Founding Fathers and the personal embodi-

ment of American Classical style. He devoted 25 years to the creation of

Mount Vernon’s New Room as a design showpiece, picture gallery, and

occasional dining room. Susan Schoelwer, its senior curator, described

that room’s evolution. Begun in 1774, its construction and decoration

The 2014 Historic Deerfield Decorative Arts Forum bro-

chure detail shows the American eagle finial from Deer-

field’s breakfront secretary, Salem, Massachusetts, 1800-10.

Amanda Lange, curatorial depart-

ment director at Historic Deerfield,

showed that Classical objects such

as obelisks were popular decorative

forms. This is one of a pair of circa

1800 English “feldspathic stoneware”

obelisks by Chetham & Woolley of

Longton, Staffordshire County. The

overglaze enamel decoration depicts

“trophies” of musical and military

imagery.

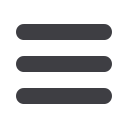

Wendy Cooper’s 1993 landmark book

could be the next stop for readers dig-

ging deeper into American Neoclassi-

cism. My copy’s signed title page also

illustrates a high point of the style.

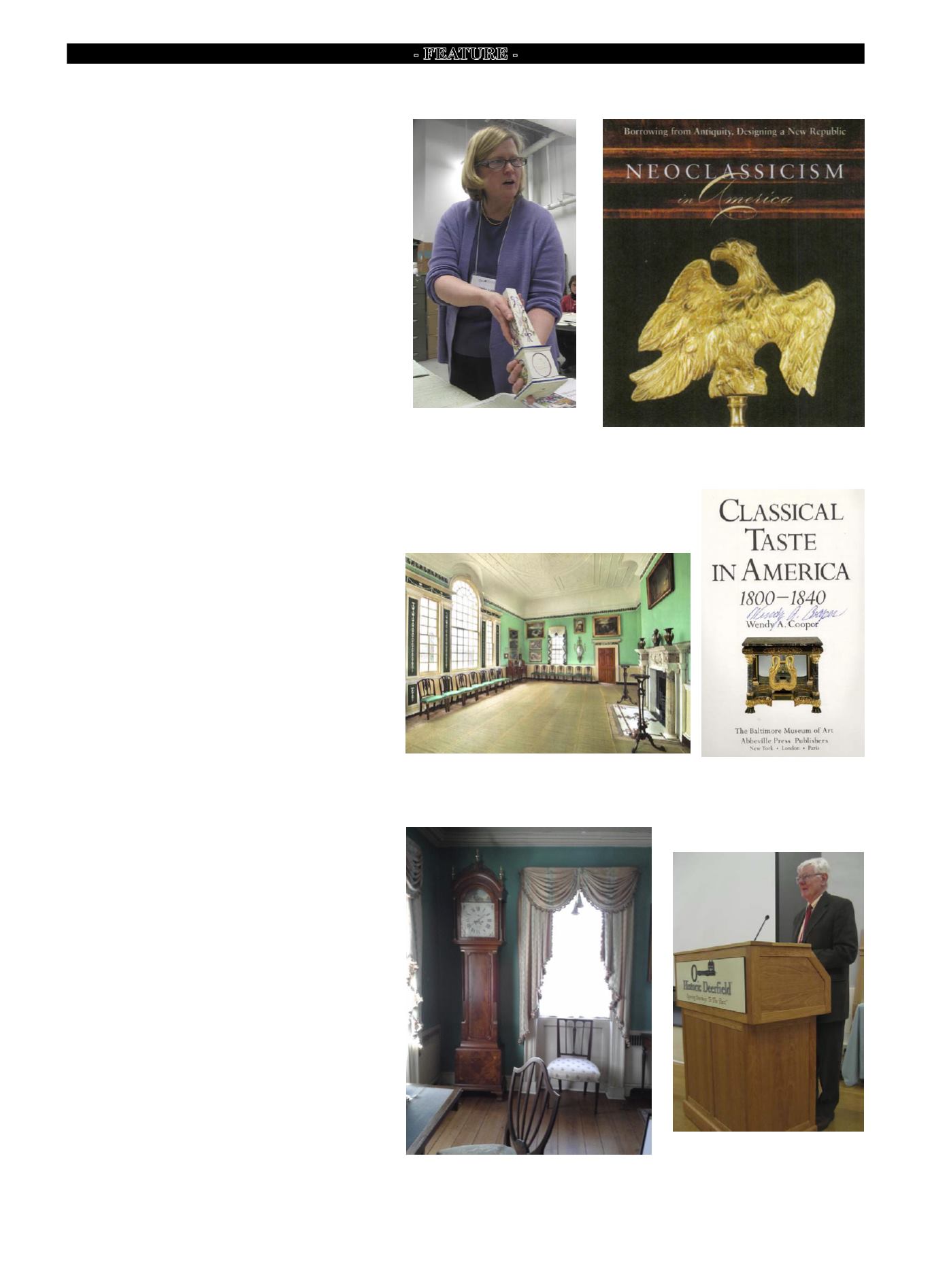

Gordon S. Wood is the Alva O. Way Uni-

versity Professor and Professor of History

Emeritus, Brown University. His latest

book, the 800-page

Empire of Liberty: A His-

tory of the Early Republic, 1789-1815

, waits

on my nightstand.

George Washington designated this as New Room at Mount Ver-

non. Senior curator Susan Schoelwer described its design, con-

tents, and importance. Photo courtesy Mount Vernon.

Asa Stebbins’s clock now stands back in the room where

it first counted the hours. The brass works and oversize

dial are by Aaron Willard; the ornate case is attributed

to Stephen Badlam.