14-C Maine Antique Digest, December 2016

-

FEATURE -

14-C

Head of the House

Wes Cowan of Cowan’s Auctions, Cincinnati, Ohio

by Karla Klein Albertson

Photos courtesy Cowan’s Auctions

“H

ead of the House” is a new feature that

explores the founder, forte, and future of

major American auction houses. In his or

her own words, the current president is asked to explain

how the business began, which specialties have been

most successful, and what new trends are influencing

the marketplace. Once the salesroom was reserved for

dealers and wealthy collectors; now auctions permeate

the marketplace. Want another Modigliani, a painted

chest, or vintage shoes for a wedding? Bidding has never

been easier. Whatever collectors demand, auctioneers

supply.

Wes Cowan fully intended to pursue an academic career

based on his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. in anthropology. But

anthropology is the study of man, and somewhere along

the way, Cowan became fascinated with the artifacts

of human history. What began as a collecting sideline

eventually became a passionate avocation. Historical

Americana was the first focus of Cowan’s Auctions,

which has now expanded into multiple departments led

by specialists: American history; American Indian art;

decorative art; fine jewelry and timepieces; fine paintings

and works on paper; historic firearms andmilitaria; modern

and contemporary art and design; and modern ceramics.

How did it all begin?

“I was a collector of artifacts when I was a kid—I

was a collector of a lot of things when I was a kid.

American Indian artifacts in particular got my attention

when I was about ten years old. I entered college having

participated in a professional archaeological dig with the

University of Kentucky and knew that I was going to

be an archaeologist. So I got my B.A. and M.A. at the

University of Kentucky and my Ph.D. at the University

of Michigan. I focused on paleoethnobotany, which is the

study of the interrelationships between past human and

plant populations. So I was very interested in the origins

of agriculture, not only worldwide but in particular in

eastern North America, and the transformation of human

populations in the East into fully agricultural societies.

I taught three years at Ohio State and then I left to be

the curator of archaeology at the Cincinnati Museum

of Natural History; I was there for eleven years. I had a

great career; I published scholarly papers. I could have

remained in that position for the rest of my life.”

When did selling antiques enter the picture?

“When I was in graduate school at the University of

Michigan, I started going to antiques shops in southeastern

Michigan and buying 19th-century photographs, because

they were cheap and dealers really didn’t know what

they had. I pretty quickly found out that there were other

people interested in collecting these things, and so by the

time I took my first job at Ohio State, I had a nice little

business buying and selling antique photographs on the

side. They are visual artifacts. I was a pretty serious and

well-known collector and dealer of stereographica and

photographica. When I was at the museum in Cincinnati,

I was conducting mail and phone bid auctions of stereo

views, and I participated in the trade shows. Many

collectors in the 1980s and 1990s became dealers to

support their hobby.

“So after I had been at themuseumfor eleven years, I got

a call to do an appraisal of 19th-century photographs—it

was part of an estate. And the attorney asked if I wanted

to buy the collection, and I said, ‘Why don’t you let

me sell it at auction?’ I got an apprentice auctioneer’s

license in Ohio and worked with a licensed auctioneer

to sell the collection—and it was a great success. And

suddenly there were messages on my answering machine

saying, when are you having your next auction? So I had

another auction six months later, and I

came home from work and there were

even more messages. After one more

auction, I thought, I’ve had a great

career as an archaeologist, and it’s time

to do something different. So I hung

out my shingle in 1995. I was working

in a small building in the rear of my

lot, a renovated garage; it was just me

and a bookkeeper basically. I was still

just selling photographs and historical

ephemera, political memorabilia, all

American history.”

When did the business begin to

expand beyond its initial focus?

“I did that for four or five years,

fending off people who told me I

should sell silver and paintings and

“I told them I had a degree

in anthropology, gave them a

proposal, and it was a great sale.”

furniture. Then I had a call about an estate that belonged

to a former curator of decorative arts at the Cincinnati

Art Museum, two housefuls of stuff, and I thought I

probably should look at it. Too much of an opportunity.

So I became a paintings, furniture, and decorative arts

auction house. I hired a recent Winterthur graduate to

catalog all these things. About a year later, the Western

Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland decided that they

were going to deaccession their North American Indian

art collection, which had nothing to do with Cleveland

and the Western Reserve. They were planning to send it

to Christie’s. I told them I had a degree in anthropology,

gave them a proposal, and it was a great sale. No one was

selling American Indian in the Midwest, only on the East

and West Coasts. I hired Danica Farnand, who is now our

director of American Indian art.

“So my business was growing very organically and

very quickly. We were growing 20% to 30% annually for

five or six years. The next addition was historic firearms

and militaria; Jack Lewis served as consultant. The busi-

ness grew when opportunities arose. It was the same way

with modern ceramics—I’ve always liked them. Some-

one connected me with

Garth Clark and Mark

DelVecchio, who had

closed their place in New

York after thirty years

and retired to Santa Fe.

I’ve been working with

them for five years. We

have a sale on October

28. The market’s razor

thin, so of all the things

we sell, it’s probably the

most challenging. There

are fewer collectors, and

the collectors who were

buying in the 1970s and

1980s can’t understand

that not everybody wants

a Peter Voulkos plate. A

natural outgrowth of this

was to sell other mod-

ern, although it meant

competing directly with

specialists like Wright

and Rago. They’re in

an environment where

there’s more product to

get. It will be difficult for

anyone outside of those

major areas to make

much of an impact, in

my opinion, because they

have the advantage.”

What do you consider

your forte?

“I think we are nation-

ally recognized for our

American history depart-

ment. I changed the name

from historical Ameri-

cana to American his-

tory because I thought a

buyer would understand that better. I think that we are

an acknowledged leader also in the sale of 19th-cen-

tury photographs, and it’s a field that has remained very

strong in the face of declining prices everywhere else.

And it’s remained fairly strong because prices never rose

too high. The material was always fairly affordable—

except for daguerreotypes. For a while the market for

those grew astronomically, driven by a handful of collec-

tors and institutions.”

What do you see for the future of Cowan’s and the

market in general?

“That’s one of the fun parts of this business—looking

into the crystal ball and trying to figure out what’s

going to happen. I will tell you that I’m not alone in

recognizing that our business is changing as we speak.

Right now is probably the most challenging time to

be in the auction business in my twenty-two years in

the industry. There is an avalanche of material to sell

because baby boomers are retiring. These collections

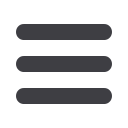

When Wes Cowan launched his auction business in 1995,

he brought with him a strong academic background in

archaeology and a passion for the ephemeral artifacts of

American history. From this foundation, Cowan’s Auctions

has grown into a diverse firm with experts in multiple fields

from American Indian art to modern ceramics.

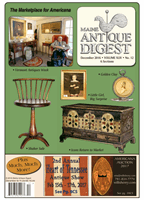

A recent American history high point at Cowan’s was this

well-documented presentation-style pipe tomahawk carried

by Captain Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809). It sold privately

in December 2015 for an undisclosed seven-figure price.

Cowan’s offers important

modern ceramics auctions

curated by experts Garth

Clark and Mark DelVecchio.

In November 2010 this Gash

stoneware stack pot, 48" high

x 16" diameter, a 1978 work

by Peter Voulkos (1924-2002),

sold for $105,750. The price

is a world record for an art-

work by Voulkos.

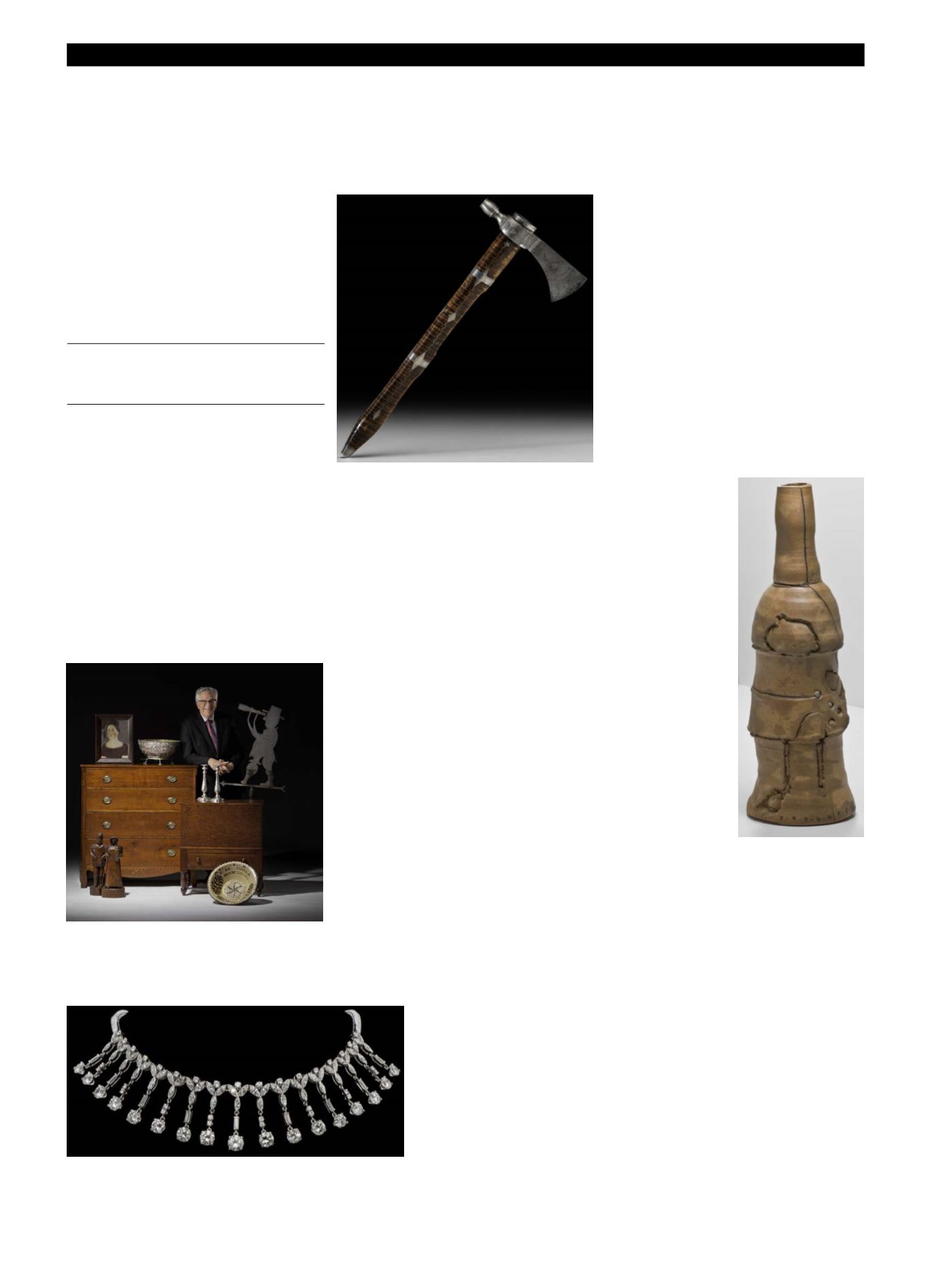

Over the last ten years, Cowan’s has sold personal belongings from the estate

of Margaret “Marge” Schott (1928-2004), owner of the Cincinnati Reds. In

addition to baseball memorabilia, there was a lot of fine jewelry, such as this

custom-made platinum and diamond necklace, which brought $192,000 in

April 2013.