Maine Antique Digest, May 2015 25-B

- FEATURE -

A

t the top of a curving

staircase in the Reese-Pe-

ters House, home to the

Decorative Arts Center of Ohio,

visitors since February 7 have

been greeted by a section of

wrought-iron balcony railing,

an arched name board from an

Ohio River steamboat, and a

crisp-looking panel announcing

the exhibition housed through

doors to the left and right. In Art

Deco-style type it reads, “A Tra-

dition of Progress: Ohio Decora-

tive Arts 1860-1945.”

Part metaphor, part metamor-

phosis,

A Tradition of Progress

offers an intriguing view of cul-

tural heritage in the Buckeye

State. Open in Lancaster through

May 17, the exhibition is the

sequel to

Equal in Goodness:

Ohio Decorative Arts 1788-

1860

, which was featured at the

same location in 2011.

Andrew Richmond, vice presi-

dent of Garth’s and a

M.A.D.

col-

umnist, returns as curator for this

second show, which in the plan-

ning stages had the working title

of

Equal the Sequel

. However,

A Tradition of Progress

found

its own identity and gained its

own voice. In the process, it did

something else. It accomplished

the nearly impossible by sum-

ming up 85 years of decorative

arts in 152 individual objects and

groupings.

The items showcased were

made in Ohio during a period

that began before the Civil War

and ended after the conclusion

of World War II. It was a time

when America had become fully

industrialized, transitioning from

handwork to machine-made

goods. And it was an era when

middle-class Americans had

enough change jingling in their

pockets to splurge on objects

that were not merely functional

but were also decorative. These

everyday folks were no Rocke-

fellers, but they could begin to

furnish their homes with nice

items that bespoke of the upward

mobility of the U.S. populace.

That’s where part of the met-

aphor comes in, as the material

found in

A Tradition of Progress

represents more than just a period

of time, but also the American

dream of living a life bigger and

better than one’s ancestors. The

metamorphosis can be seen in the

five rooms where the exhibition

is presented, as visitors advance

counterclockwise,

essentially

turning back time. Distinct peri-

ods within the framework of the

exhibition get their own space.

The show picks up where

Equal in Goodness

left off, in the

middle of the 19th century, when

individuality and quality work-

manship were expressed through

objects such as an ink and water-

color family register from Allen

County, a fraktur depicting birds,

roses, and tulips, and with dates

ranging from 1848 to 1889; a

large double-handled salt-glazed

water cooler with a cobalt dec-

oration of a bird on a branch,

lettered “Harley & Carll/ Ohio

Stoneware/Akron O” and dated

1876; and an 1885 paint-dec-

orated blanket chest by Jacob

Werrey of Fulton County.

Through the next doorway, one

steps into the Gilded Age, repre-

sented by a pair of ceramic pot-

pourri jars made by the Homer

Laughlin China Company of

East Liverpool, urn-shaped ves-

sels having white-on-blue ovals

depicting Classical figures, rem-

iniscent of Wedgwood’s cameo

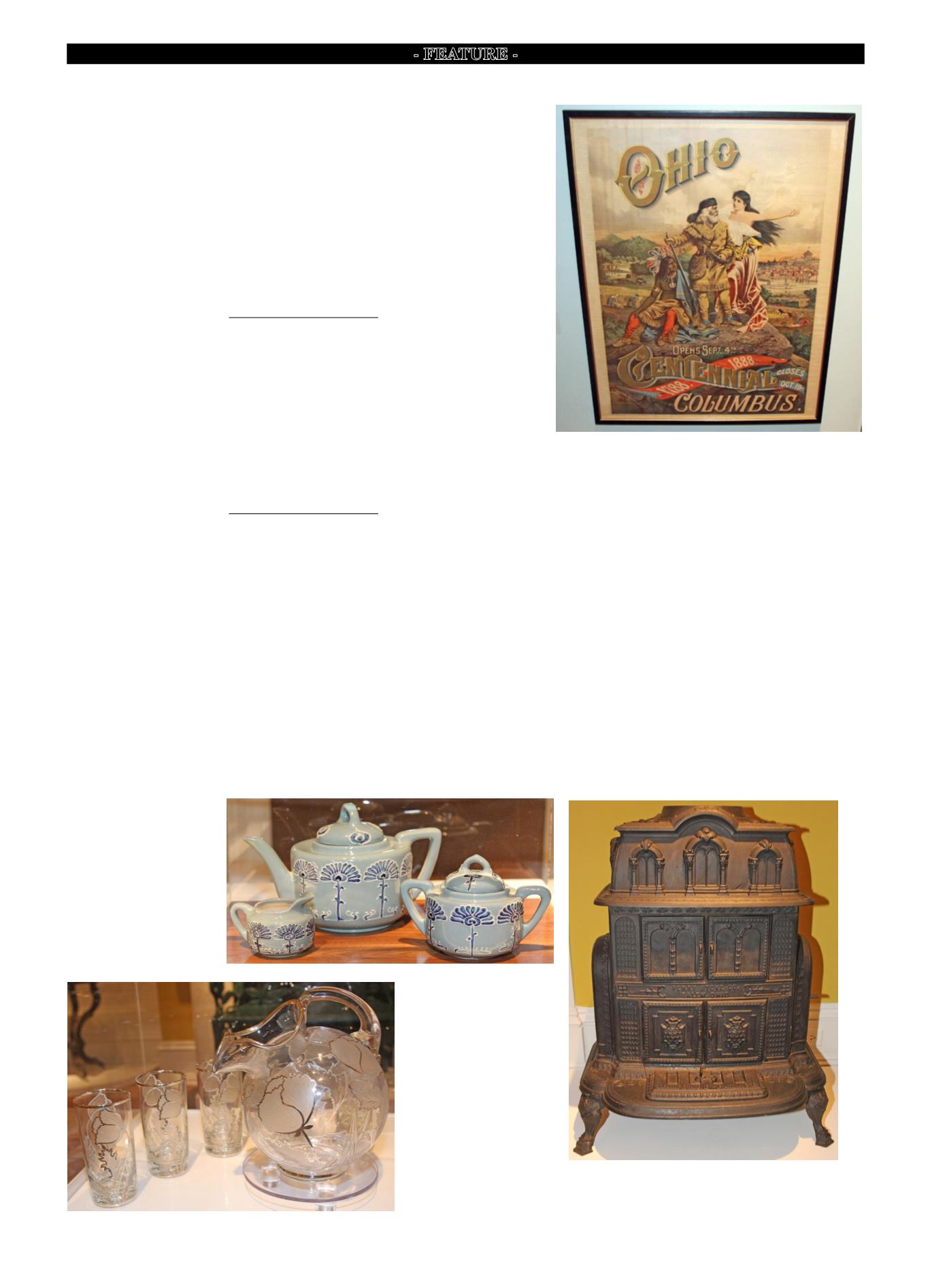

wares. In contrast, a cast-iron

parlor stove made by Perry Stove

Company of Salem exemplifies

how even the most utilitarian of

items were sometimes crafted

with a flair, as the stove takes the

form of a Second Empire-style

house.

The next doorway moves vis-

itors to the late 19th century,

with the large, clunky furniture

of the Victorian era offset by

the bright, strong graphics of

the period, the latter represented

by a number of items related to

Ohio’s centennial celebration in

1888, including colorful broad-

sides printed by the Krebs Lith-

ographing Company of Cincin-

nati, as well as trade cards given

away by merchants in hopes

of promoting business. These

include one for the Cleveland

Dryer Company of Cleveland,

which illustrated the transi-

tion from log cabins to modern

farms, all the while promoting

bone phosphate fertilizer.

Another doorway, another era,

as the Arts and Crafts movement

is explored, with Cincinnati art-

carved furniture highlighted by

a fireplace mantel carved by

Henry Fry and a writing desk

carved by his son, William Fry.

The sunflower motif of the man-

tel is seen again on a glazed

architectural tile by Mary Lou-

ise McLaughlin of Cincinnati,

one of a variety of pieces of art

pottery from makers that include

Ohio’s big three: Rookwood,

Roseville, and Weller. Arts and

Crafts furniture includes a pair

of tall-back side chairs by the

Shop of the Crafters of Cincin-

nati, while metalwork is repre-

sented by a brass, copper, and

enamel sconce by Horace E.

Potter of Cleveland and a silver

and ivory letter opener by Potter

Studio, also of Cleveland.

The final room takes visitors

toward the modern era, high-

lighted by a variety of Art Deco

pieces, including a Jazz bowl

designed by Viktor Schrecken-

gost and made by Cowan Pottery

of Rocky River; a circa 1933

quilt in blue, gray, and white,

showing skyscrapers, dirigibles,

and airplanes, crafted in Akron;

and even the most mundane of

household artifacts, a Hoover

vacuum sweeper and a Kitchen-

Aid stand mixer.

At times the same company is

represented from room to room,

showing the variety of its output.

That’s most apparent with Rose

Iron Works, founded in 1904 and

still in business in Cleveland.

The wrought-iron railing that

greets visitors at the entrance to

the exhibit is Rose Iron. A pres-

entation drawing for a Rose Iron

chandelier hangs among the

Gilded Age material. A pair of

floral-motif andirons from Rose

Iron, accompanied by a related

design drawing, appears with the

Arts and Crafts goods. The room

highlighting Art Deco contains

a pair of cactus-motif andirons

and a concept drawing, as well

as a table lamp.

Putting it all together was no

easy chore.

Richmond noted that

A Tra-

dition of Progress

was harder to

pull off than

Equal in Goodness

.

“In part, because I moved well

into territory about which I had

little knowledge,” he said. “By

the time I began work on

Equal

,

it was well-trodden terrain for

me. But for

Tradition

, I had so

much to learn. I was comfort-

able with my knowledge of Ohio

history and culture during that

time period, and I certainly was

familiar with many of the mak-

ers (Mitchell and Rammelsberg,

Heisey, Cowan, et cetera), but

it’s such a complex story. Such a

big story. And the sheer volume

of material that is available to

cover this time period is utterly

Tradition of Progress

Exhibit

by Don Johnson

The show picks

up where

Equal

in Goodness

left

off, in the mid-

dle of the 19th

century, when

individuality

and quality

workmanship

were expressed

through

objects.

Second Empire architecture is mimicked

in the design of this parlor stove, made

circa 1875 by the Perry Stove Company,

Salem, Ohio. Fancy stoves such as this

were often placed in rooms where guests

were entertained.

Cambridge Glass Company

items shown at

A Tradition

of Progress

include this ball

pitcher and eight matching

tumblers. In the #3400 line and

with applied silver decoration

at the edges of the flowers and

some leaves, this set dates to

the 1930s or 1940s.

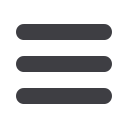

Lithographs celebrating Ohio’s centennial in 1888 included this one

printed by the Krebs Lithographing Company, Cincinnati. Exhibitions

marking the anniversary were held in Columbus and Cincinnati.

Jap Birdimal was one of two

important lines created by British

potter Frederick Hurten Rhead

during the short time he spent

working at Weller Pottery in

Zanesville, Ohio. This set is circa

1904.