4-A Maine Antique Digest, April 2015

The Meeting Place

THOMAS GILPIN

ATTRIBUTION

Dear Clayton and Lita,

I just read your first overview

of Americana Week of 2015 in

the on-line edition of

M.A.D.

(March, p. 32-B) and wanted to

note a correction regarding the

description of the comb-back

Windsor armchair in rare orig-

inal green paint that we sold at

the Winter Antiques Show. The

armchair was not branded by

Thomas Gilpin, but instead was

attributed to him based on other

signed examples. Thanks.

David A. Schorsch

via e-mail

GUN ENTHUSIAST,

EX-SUBSCRIBER

To Whom It May Concern:

I am not renewing my

subscription after many years.

The reason, I thought you should

know, is your editorial last year

(see

M.A.D.

, July 2014, p. 3-A)

clearly showing your anti-gun

stance. You may not have many

that will not renew, but I am one.

Brad Davis

Hamilton, MT

(

M.A.D.

is not anti-gun. We

editorialized against a proposed

law to change the definition

of an “antique” firearm. We

wrote, in part: “Congress should

reject this bill. The market for

antique firearms is booming, and

the common-sense regulations

outlined in the 1968 Gun Control

Act don’t seem to be restricting

the trade in any measurable way.”

The proposed bill, which died

when the new Congress took over

in January, was reintroduced on

February 26. Ed.)

BUYER’S PREMIUM

Dear Clayton,

I just have to comment on the

innocuous placement of your re-

porting that Sotheby’s raised its

buyer’s premium in the “Frag-

ments” section of the March

edition on pg. 8-A. It is really a

shame that there is such a gen-

eral acceptance of not only these

ever rising fees, but all the other

devious methods that it and its

“partner” Christie’s perpetrate

on the industry.

When the Sotheby’s/Chris-

tie’s duopoly talk, people listen.

When they take advantage of

both buyers and sellers with de-

ceptive formats, fees, and price

manipulation, people still just

listen and enjoy being fleeced

some more.

Lewis J. Baer, Newel, LLC

New York, NY

BROWN FURNITURE

To the Editor:

Maine Antique Digest

is one

of the leading trade periodicals

in the antiques business and as

such should advocate for the

enterprise. Instead, I was disap-

pointed again with the “dumbed

down” description of “brown

furniture” in your coverage of

Garth’s auction (page 22-D,

March 2015 issue). What if the

highlighted quote had read,

“How about paint dabbed on

canvas as the top lot of the sale?”

I imagine there would be outrage

among art lovers who recognize

the skill, mastery, and emotion

the artist imbued his/her efforts

with. Likewise, skilled artisans

spent lifetimes learning how to

create not only useful, but beau-

tiful furniture. Understanding

proportions, design, construc-

tion techniques, and wood prop-

erties is no paltry task.

If you want to know what is

wrong with the furniture market,

look no farther than your mirror.

For at least five years, the dis-

paraging catchall description of

brown furniture has been creep-

ing into your newspaper. To quote

from “The Young Collector” arti-

cle on page 22-A of your March

2015 issue, “We don’t construct,

hatch, make, or even manufacture

collectors; we cultivate them.”

What kind of collector can you

expect to cultivate when even the

advocate sweeps aside the excel-

lence of an entire category of dec-

orative arts?

Scott A. Cilley

Richmond, VA

(Our highlighted quote in the

story was “How about brown

furniture as the top lot of the

sale?” We don’t think using the

term “brown furniture,” long

used in the antiques trade, is

disparaging in any way. Ed.)

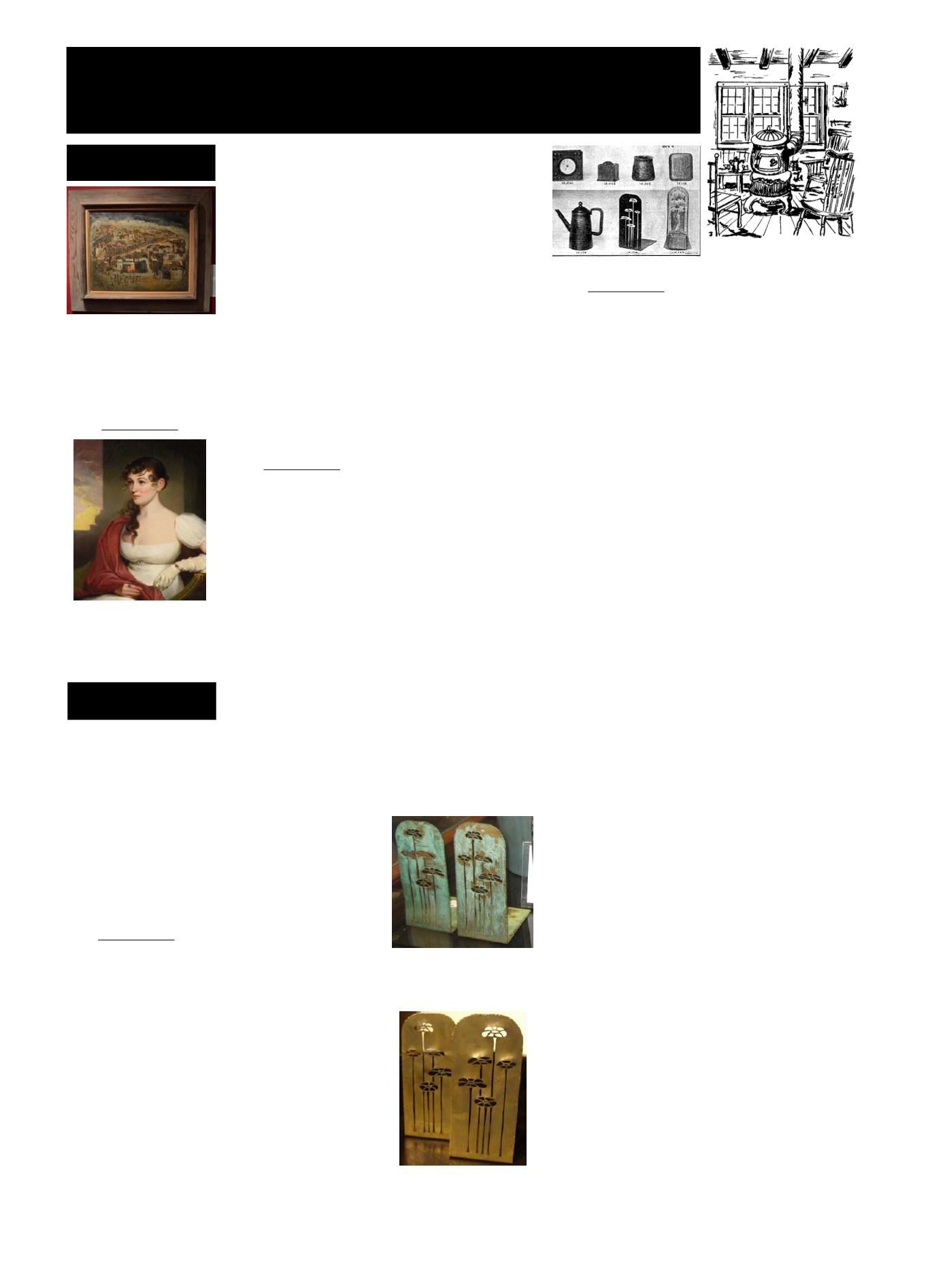

NEWCOMB OR NOT?

To the Editor:

The brass bookends shown on

page 7-B of the March 2015 issue

are described as being the work

of Newcomb College. I disagree.

Unless Newcomb College made

exact duplicates (which I strong-

ly doubt), they are the work of

the Forest Craft Guild.

As for sources of attribution,

the most powerful is a primary

source. Google Books has a copy

of

The American Stationer

, Vol.

LXVII, No. 11, dated March 12,

1910. On page 30 of that mag-

azine is an article on the Forest

Craft Guild with a photo of some

of their products including the

bookends in question.

Another source for attribution

is the Dalton’s American Deco-

rative Arts Web site (www.dal tons.com). Dalton’s is one of thenation’s premier dealers in Arts

and Crafts antiques, and it has a

signed pair of the bookends in

the “Sold Archives” section of

its Web site.

I’m not an expert in Newcomb

College metal, but the verdigris

finish on the bookends is not

something they normally do.

Verdigris finishes are a hallmark

of the Forest Craft Guild.

Timothy Grier

Arlington, VA

(Neal Auction Company cataloged

the unmarked bookends as

Newcomb College, citing an

almost identical pair shown in

the 2002 book The Newcomb

Style: Newcomb College Arts &

Crafts and Art Pottery Collector’s

Guide by Jean Bragg and Susan

Saward. Pictured on page 154, the

bookends are said to be the work

of Rosalie Roos Wiener, a noted

Newcomb metal craftsman.

David Rudd at Dalton’s

American

Decorative

Arts,

Syracuse, NewYork, forwarded us

a photo of the marked pair he sold,

and we were able to reproduce a

portion of

The American Stationer

.

In an odd coincidence, the Forest

Craft Guild products were being

sold at George E. Newcombe &

Co. Ed.)

On page 14-B of this issue,

we used the wrong photograph

to illustrate the Jacob Eichholtz

portrait that sold for $13,750 at

Sotheby’s. The correct photo is

above.

In our story on the Boston

International Fine Art Show

(March, page 10-D), we reported

an incorrect price. Gina Knee’s

(1898-1982) 1947

Southern Sun-

day Afternoon

, a 14" x 30" oil on

canvas offered by Susanna J.

Fichera Fine Art, was $26,000.

It has since sold to an institution.

Advertisement from

The

American Stationer

.

The pair sold for $2868 (est.

$1500/2500) at Neal Auction

Company on November 22, 2014.

Karla Klein Albertson photo.

Forest Craft Guild bookends with

cut flowers, 7 1/8" x 3¼" x 4½"

deep, with stamped mark. Photo

courtesy

Dalton’s American

Decorative Arts.

AGAINST THE MACHINE

To the Editor:

It happened again. I had reg-

istered an absentee bid on an

item in an auction several states

away, and it was a tie bid. What

I mean is, it would have been a

tie bid because my bid was the

same price the item sold for, ex-

cept that the auctioneer didn’t

get a chance to place the absen-

tee bid I had left with him. As

always happens, the tie went to

the Internet bid, not to my bid,

even though they were identical.

As I understand it—and I admit I

may not have the correct under-

standing of all the electronics—

this is because Internet absentee

bids have an unfair advantage

over other absentee bids.

This auctioneer, like many

nowadays, allows bidders to

bid in numerous ways, but they

all fall into two categories: ab-

sentee and live. Absentee bids

are placed ahead of time, either

with the auction house itself (via

mail, absentee bid forms, per-

sonal contact, entering bids on

the auctioneer’s Web site, etc.)

or with an independent Internet

service such as Invaluable, Prox-

ibid, LiveAuctioneers, etc. Ab-

sentee bids that are registered di-

rectly with the auction house can

be either entered into the house

computer system or placed live

during the auction by a member

of the staff—a further compli-

cation. Live bids (the tradition-

al method) can be placed by a

living human at the moment the

item is being auctioned: either

from the auction floor (raising

a paddle, screaming to get the

auctioneer’s attention, etc.), via

phone, or via an on-line service

(Invaluable, Proxibid, LiveAuc-

tioneers, etc.).

Competition is an essential

part of this whole process, and

the assumption is that all bid-

ders have an equal opportunity

to make their highest bid known

and have an equal chance of

its being accepted. Usually it

works. When one bidder bids

more money than any other bid-

der, the other bidders might be

disappointed, but they wouldn’t

say that the process was unfair or

biased. After all, that one bidder

was willing to pay more than all

the other bidders, and that bidder

got the item. That’s what should

happen.

But the situation is differ-

ent with tie bids or equal bids.

That’s when two or more bid-

ders intend to bid the exact same

price, which then turns out to be

the highest price, the winning

bid. In this case, it is the bidder

who bids first who gets the item.

By this I mean the bidder whose

bid is the first among all these

equal bids to be accepted by the

auctioneer. And here is where

tie bids on the Internet have a

distinct advantage over tie bids

placed on my behalf by the auc-

tion house, or placed by live bid-

ders on the phone, or placed by

live bidders in the room.

This happens for two reasons.

First, during the auction, as I un-

derstand it, computers are mak-

ing absentee bids in hundredths

of a second; second, when sev-

eral

identical

absentee bids are

made on line before the auction,

the first bidder has priority, and

any other bids for the identical

amount are canceled. However,

an absentee bid that was made

prior to all of them

via the auc-

tioneer

doesn’t cancel any In-

ternet absentee bids of equal

amount.

Let’s look at these one at a

time. If you’ve attended a live

auction that’s also accepting

bids on the Internet, you know

what sometimes happens. The

auctioneer opens the bidding.

There’s a flurry of on-line ab-

sentee bidding that rises to a

certain amount and stops. At

that time, live bidders (on line,

on the floor, or on a phone) can

weigh in with their bids. When/

if the bidding continues, a floor

bidder might be bidding against

an Internet absentee bid or a live

Internet bidder or bidders in the

room or on the phone. The result

is the same: the highest bid gets

the item.

But what about this scenario:

the lightning-quick bids rise to

the exact amount you were wait-

ing to bid. Let’s say the highest

bid is a tie at $50. Some Inter-

net absentee bidder registered

a $50 bid several days earlier,

and when bidding opens on the

item, the computers start calcu-

lating all the various absentee

bids: canceling all the $25 bids

and the $30 bids, eventually see-

ing the $45 bids, and applying

the next increment to get to $50,

which only one bidder has regis-

tered. His $50 bid is placed. Un-

fortunately for you and me, he

got first crack at bidding his $50,

and you didn’t have a chance to

compete with him. You couldn’t

get your paddle up fast enough

in those lickety-split moments to

make that bid. The winning bid

was made automatically, a hun-

dredth of a second after the $45

bid. Your bid had the potential

to be the winning bid, but you

couldn’t raise your paddle in a

hundredth of a second.

You, like the auctioneer, have

turned into a spectator at the

real auction, which was happen-

ing on line. The auctioneer was

no longer asking for bids (“Do

I hear $50?”) or accepting bids

(“I have $50”). In fact, he wasn’t

an auctioneer anymore. He was

a mere human who became a

spectator at his own auction. He

had given his legal authority to

accept bids over to another party.

This is like the auctioneer an-

nouncing as the auction starts:

“I’m going to let the people in

the front row bid until they’re

done, then everybody else can

bid if they want to.” This process

Corrections

Letters