Maine Antique Digest, April 2015 21-D

- AUCTION -

R

uth Nutt’s collection of silver was the fin-

est and most comprehensive collection of

American silver ever to appear at auction. It

spanned the 17th century to the present, including

masterpieces and rare regional examples, intrigu-

ing small pieces such as school prizes, Masonic

medals, a policeman’s badge, and such unusual

forms in American silver as a bidet and a bone

holder for carving a leg of lamb. There was a

parade of coffeepots, teapots, tankards, canns, por-

ringers, and pepper pots from

the 17th and 18th centuries, a

hot water urn, and tureens and

sauceboats by Fletcher and

Gardiner, Federal silversmiths

to the new nation. The only

thing missing was Tiffany and

mixed metals. Ruth Nutt gave

a tankard by Tiffany & Co.,

titled

Son Chow

, created for

the World’s Columbian Expo-

sition in 1893, to the Seattle

Art Museum.

Amuseumcould have bought

this well-curated collection to

tell the story of the silversmith’s trade in Amer-

ica, but it was never offered in its entirety. Ruth

Nutt (1934-2013) gave the Seattle Art Museum

more than 40 pieces of American silver along with

paintings, furniture, and needlework that had been

on long-term loan; the rest was auctioned at Sothe-

by’s on January 23 and 24. Museums, collectors,

and the trade bought 381 of the 422 lots offered

in their single-owner silver sale for the Nutts on

January 24 for a total of $4,738,789, about midway

between the estimate of $3.8/5.8 million figured

without buyer’s premium. The sale was 90.3%

sold by lot. According to Sotheby’s head of silver

John Ward, there are still more than 300 items to be

sold; some will be offered next January, and some

small items such as spoons may be offered on line

so they can be sold one at a time.

The best of the best was offered first. “We

wanted to produce a sale that would be a monu-

ment to Ruth’s taste and collecting,” said John

Ward, who masterminded the sale. Apparently

Ruth Nutt wanted others to have as much fun col-

lecting as she did.

“The fact that we could move pieces at good

prices to acclaim and enthusiasm gives me hope

for the future of the American silver market,” said

Ward after the sale. He said he was gratified to

see furniture collectors come back into the silver

market and new collectors appear in the crowded

salesroom.

Ruth Nutt did most of her buying through

dealer Jonathan Trace of Portsmouth, New Hamp-

shire. Trace was her number one advisor, and he

advised her well. She also bought from others,

such as Michael Weller of San Francisco, Robert

Jackson and Ann Gillooly of Doylestown, Penn-

sylvania, and Hinda Kohn in the early days. She

bought Fletcher and Gardiner pieces from Hirschl

&Adler. All are noted under provenance in the sale

catalog.

“She had a great eye. She liked the unusual,”

said Trace after the sale. “She didn’t care who

made it; it was the object that mattered; the history

and maker were secondary. That is why she did

not have a lot of Paul Revere.” Trace said the first

thing he sold her was a ladle at the Kent Antiques

Show in the late 1960s. “I was a kid,” he said.

The sale brought new energy to the marketplace

for American silver, but because so much was

offered at one time and so many silver collectors

have died in recent years, prices were generally

reasonable, some just a fraction of what Ruth Nutt

paid.

Works of outstanding quality, rarity, and con-

dition—the masterpieces—brought a premium.

Some regional silver from South Carolina, Wil-

mington, Delaware, and Albany, New York, sold

well above estimates. Church silver, once thought

rare and out of reach, is nowmore common because

so much has come on the market, and some by the

earliest makers failed to sell. A pair of American

beakers by Boston’s Jacob Hurd, circa 1737, the

gift of Theophilus Burill Esq. to the first Church

of Christ in Lynn, Massachusetts, estimated at

$80,000/120,000, failed to get a bid. In June 1992

at Sotheby’s, they sold for $82,500 to Trace.

The two top lots in the sale—a pair of

silver bottle stands made in New York by

Myer Myers, circa 1765 (est. $250,000/

350,000) and a two-handled cup by

Charles Le Roux made in New York, circa

1720 (est. $300,000/500,000)—each sold

for $389,000. They were bought by two

different longtime private collectors.

Museums bought the next two on the

top-ten list. A rare War of 1812 eagle-

head sword by Fletcher and Gardiner, made

in Philadelphia and dated

1828, sold for $257,000 (est.

$150,000/250,000) to the Win-

terthur Museum, underbid in

the salesroom by dealer James

Kochan of Catskill, New

York, bidding for a client. A

large sugar box and matching

tea caddy by Simeon Sou-

maine, made in New York,

circa 1720, sold for $221,000

(est. $200,000/300,000) to

Tim Martin of S.J. Shrubsole,

bidding for the Metropolitan

Museum of Art. “One of the

things that became apparent was a lot of people

had knowledge of Ruth Nutt’s intention to leave

the sugar box and tea caddy to the Met, and nobody

bid on it. It was an amazing buy,” said Martin after

the sale.

Works of the highest merit were not overlooked.

A pair of silver waiters by Simeon Soumaine,

New York, 1738-40, sold for a $161,000 (est.

$100,000/150,000) to Deanne Levison for col-

lectors. They each have engraved mirror ciphers

“EC” within a circle for Elizabeth Harris Cruger.

Trace bought one at auction for $81,250 at Sothe-

by’s in January 2002 and bought the other pri-

vately to unite two masterpieces. The same buyer

got a tiny dram cup by John Coney, Boston, circa

1680, for $75,000 (est. $15,000/25,000). It fetched

$90,500 when it last sold in January 2000. A spoon

tray engraved with a cipher, probably that of Ann

and John Bartram, a Philadelphia naturalist, sold to

dealer James Kilvington of Greenville, Delaware,

for $50,000 (est. $20,000/30,000), underbid by

Deanne Levison. At Christie’s in January 1996, it

sold for $48,300.

Two pieces of historic Philadelphia silver

expected to be among the top ten did not sell.

There was no bidding on a large salver by Richard

Humphreys, made in 1775 for Philadelphia Quaker

merchant George Emlen, that had sold at Sothe-

by’s in New York in January 1997 for $299,500

(est. $250,000/350,000), and there was not a bid

for a Philadelphia silver salver on feet by Henry

Pratt (est. $200,000/300,000) that sold at Christie’s

in January 1998 for $453,500 when it was the most

expensive piece of American silver. At that sale,

Jonathan Trace was bidding against Philadelphia

Museum of Art curator Jack Lindsey, who wanted

it for his exhibition

Worldly Goods

in 1999. Ruth

Nutt lent it to the exhibition. It is a rare form, but

others of that form have turned up since.

Some rarities seemed reasonable. Winterthur

bought an octagonal sugar bowl by Joseph Rich-

ardson Sr. for $81,250 (est. $70,000/100,000).

It is closely related to two other octagonal sugar

bowls by Richardson. One made for Oswald and

Lydia Peel sold at Christie’s, New York, January

21, 2000, for $310,500. Another made for Samuel

Emlen from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Walter

M. Jeffords sold at Sotheby’s on October 29, 2004,

for $265,000.

There was some keen competition for other

pieces of Philadelphia silver. A baluster-form tan-

kard by John Bayly, made in Philadelphia, circa

1775, with the “CSM” cipher for Christopher and

Sarah Marshall and “PM” engraved on the han-

dle for their granddaughter, sold for $87,500 (est.

$20,000/30,000) to dealer Jonathan Trace for a col-

lector, underbid by John Ward on the phone. Other

baluster-shaped tankards brought substantially

less. The cover lot, a baluster-form tankard with

mid-band by Joseph Richardson Sr., sold on the

phone to John Ward, underbid by Kevin Tierney,

for $22,500 (est. $12,000/18,000), and still another

baluster-form tankard with a mid-band, made circa

1780 by Andrew Underhill in New York, sold

to Kevin Tierney on the phone for $20,000 (est.

$10,000/15,000). Rarity, quality, and history make

the difference.

Sotheby’s, New York City

The Silver Collection of Roy and Ruth Nutt

by Lita Solis-Cohen

Photos courtesy Sotheby’s

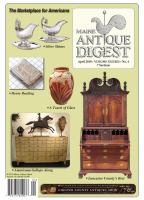

A rare pair of American silver bot-

tle stands, Myer Myers, New York,

circa 1765, each circular with scroll-

ing openwork fret-sawn sides, centering

on a solid cartouche monogrammed “SSC,” fitted with

turned wooden

bases. They are marked on the back of the cartouche

“Myers”

in a con-

forming rectangle. The diameter is 5 1/8". The pair sold for $389,000

(est. $250,000/350,000) to Atlanta dealer Deanne Levison in the sales-

room. At Christie’s in January 1996, they sold for $299,500.

“The fact that

we could move

pieces at good

prices to acclaim

and enthusiasm

gives me hope for

the future of the

American silver

market.”

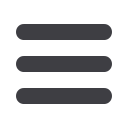

A large planished

silver oval bowl,

by Marie Zim-

mermann, New York,

circa 1921, marked

on base “Marie Zim-

mermann—Maker,”

16½" in diameter, 73

oz. 15 dwt., sold on the

phone for $16,250. Zimmer-

mann created this or another

of this model as a wedding

gift for meatpacking heir-

ess Lolita Armour of Chicago

and Santa Barbara. The set may have been commissioned by Albert

and Adele Herter. The shape was also made by the artist in copper. See

The Jewelry and Metalwork of Marie Zimmermann

(2011) by Deborah

Dependahl Waters, Joseph Cunningham, and Bruce Barnes.

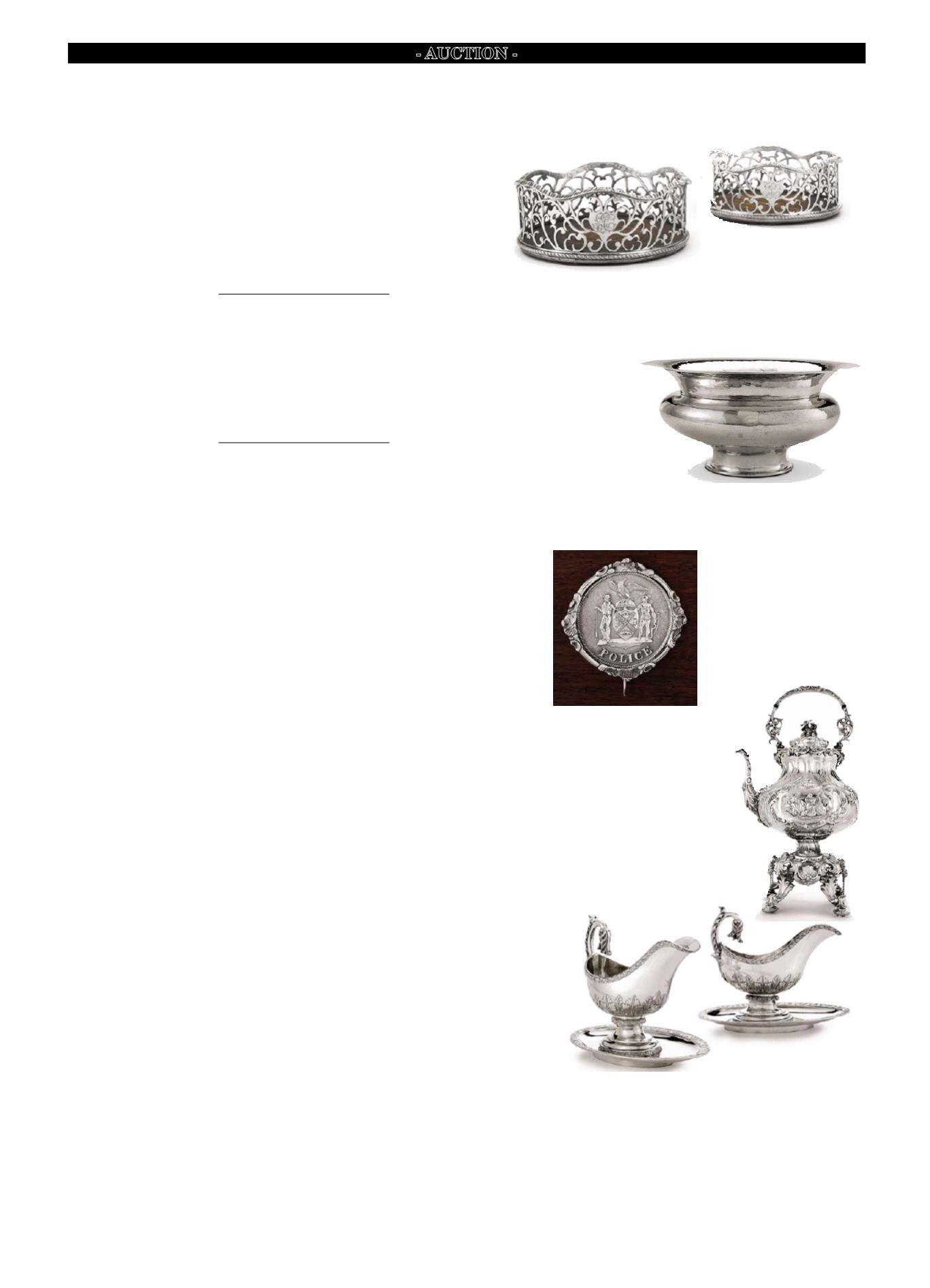

American policeman’s badge,

New York, dated 1849, the back

engraved “Joseph Britton, Esq.

Aldr 15th Ward 1849,” 2½" in

diameter, sold on line for $1375

(est. $400/600). Joseph Britton was

also an ice dealer, according to the

catalog. The 15th Ward stretched

from Houston Street to 14th Street

and from Sixth Avenue and Han-

cock Street east to the Bowery.

Monumental American silver kettle on lamp

stand, made by Lincoln & Foss, Boston, circa

1850, of good quality and good weight

and of unparalleled scale for American

silver made before the Civil War, sold

in the salesroom to Tim Martin of S.J.

Shrubsole, New York City, for $23,750

(est. $10,000/15,000) for the St. Louis Art

Museum. It is boldly chased with scrolling

leafage, the side applied with 18th-century

fêtes galantes,

the back cartouche engraved

with a crest of a griffin’s head erased with a

star in its beak, the hinged cover with a flowering

sprig finial, on a matching stand with detached

lamp, marked on the base of the kettle and

burner, 171 oz. 5 dwt., 21" high.

A pair of large American silver sauceboats and stands by Thomas

Fletcher, Philadelphia, 1830-35, engraved with a crest “SCP 1877 to

ABP 1895” and on the base “Anne R.P. Burroughs 1855/ Sarah C Ken-

nard-1877/ Anne B. Pierce 1895,” marked on the base “T.FLETCHER/

PHILAD,” stands are 11" wide, 82 oz. 5 dwt. The pair was made for the

Pierces of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, who bought a large group of sil-

ver from Fletcher in the 1820s and ’30s. They have been widely exhibited.

They sold on the phone to a collector for $62,500 (est. $20,000/30,000). At

Sotheby’s in November 1976, just one of these sauceboats sold for $2500

to Elizabeth Feld of Hirschl & Adler. Hirschl & Adler either had the

other or found it and sold the pair to Ruth Nutt in 1999.

☞