Maine Antique Digest, March 2015 35-C

- FEATURE -

The cover has a circular mark on it obviously made by the bottom

of a wet drinking glass. “That’s how much they thought of it,” Tane

said of whatever previous owner had been so careless. “They used it

for a coaster.” That afternoon at her apartment, the coaster Tane gave

me to put under my teacup was a facsimile of that abused cover—

from a set given to her as a gift by Loewentheil.

With both

The Raven

and

Tamerlane

in her possession, Tane had

to make a decision. She could go on to collect other high spots of

19th-century literature or she could concentrate on Poe. Icon-buying

is the style of collecting preferred by many new collectors, perhaps

because, although it takes more money, it takes less time. Nonethe-

less, while Tane does now have notable works by other 19th-century

masters, she decided at that turning point to dive deeply into Poe, col-

lecting not only first editions and manuscripts but also letters, peri-

odicals, newspapers and other ephemera, Poe artifacts, Poe-inspired

artworks, books about Poe, illustrated Poe titles, and all sorts of other

Poeana. What is Poeana? Here’s one example from the Tane collec-

tion: a copy of

Register of the Army and Navy of the United States

for

1830, where Poe is listed on page 84 as a student at the U.S. Military

Academy at West Point. (He was there for seven months, dismissed

for deliberately bad behavior in January 1831.)

“I often give talks on collecting, and I tell people that, rather than

getting high spots, you can develop a much more important collec-

tion if you specialize in one area,” Tane told me. “It wasn’t that I was

so smart. It was just more interesting to me to do that.”

Tane’s story of Poe begins with his forebears, a complicated family

tree. Numerous pieces of ephemera represent the theater backgrounds

of some of his biological relatives. These include two playbill broad-

sides advertising performances by Poe’s grandmother Elizabeth

Arnold and copies of plays in which Poe’s parents performed. Tane

has, from Poe’s adoptive family, a seven-piece decanter set, each

piece etched with an “A” monogram. The set was originally owned

by Poe’s foster father, John Allan. It came to Tane from “a man who

was selling some of his things down south,” said Tane. “People who

have things find me. They want me to have them. They know I’ll take

good care of them and that I’ll share them.”

Items that relate to Poe’s early successes include not

just Tane’s rarer than rare

Tamerlane

, which has

been called “the black tulip of American litera-

ture.” She also has such things as a copy of the

periodical in which his prize-winning tale of 1833,

“MS. Found in a Bottle,” was published. An auto-

graph manuscript of Poe’s early tale “Epimanes,” is

another of her treasures. A single folded leaf of four

pages, it is the only Poe tale, early or late, in private

hands. I was shown “Epimanes” in Tane’s library

on the afternoon of my visit and marveled at Poe’s

tiny handwriting that resembles lacework. I marveled

again at the perfectly formed rows of inked words

when I saw “Epimanes” and other manuscripts in the

exhibit. This evidence of his steady hand is particularly

notable considering the notoriously unstable nature of

his mental life.

As Poe’s literary stature grew, he began to attract

fans. A book (not one of Poe’s own) that he inscribed

to a young admirer is part of Tane’s collection. He also

acquired unimpressed critics, one of whom described

The

Raven

as “a parcel of current trash.” He had numerous lit-

erary feuds over what critics said about him and what he

said as a critic about others. That’s par for many a writer, but

when he got himself involved with two married women (an

image of one, Frances Sargent Osgood, is owned by Tane),

the scandal led to his banishment from the New York branch

of the literary world.

Poe’s famous tale “The Cask of Amontillado,” whose

protagonist’s plot of revenge is ignited by an insult, reflects

some of the anger Poe felt toward his banishers, Tane specu-

lates in her catalog. More overtly autobiographical is his poem

“Ulalume,” which first appeared in

The American Review: A Whig

Journal

in 1847, a copy of which Tane has in original wrappers. The

poem was inspired by the death of Virginia Poe within the same year.

The poem’s narrator wanders through a landscape with “ashen and

sober skies”—a “ghoul-haunted woodland”—until he comes upon

the tomb of his beloved on the anniversary of her death.

When Poe married Virginia, she was 13 and he was 27. Poe’s first

cousin, Virginia died at age 24. Poe himself died two years later at

age 40. “There was a terrible obituary of Poe written by Rufus Gris-

wold that starts with something like, ‘He’ll be missed by nobody,’”

Tane said. Actually, the wording was “He had few or no friends,” and

it is true that only eight people attended his funeral. His write-up in

the

New-York Organ

, a weekly journal devoted to the cause of tem-

perance, was no better than Griswold’s. It called Poe an “unhappy,

self ruined man.” Poe’s cause of death, however, has never been

determined.

A traditional biography would end there. Not this one. Poe’s after-

life, as Tane calls it, is the subject of the second half of her Poe story.

In that afterlife, Poe’s literary greatness was gradually understood;

his reputation underwent repair; and even his bodily remains were

exhumed and dealt with more reverently than they had been upon his

demise. Buried in Baltimore in the Poe family plot, he was relocated

in 1875 to a new marble monument in the city’s Westminster Hall

and Burial Ground. At the time of the exhumation, artifacts were

“collected,” including coffin fragments. Tane owns one.

In 1909, the centenary of Poe’s birth, there were celebrations

and publications. The Grolier Club itself issued a bronze memorial

medallion, sculpted by Edith Woodman Burroughs, in an edition of

277. Tane has one of them. On September 26, 1930, the first meeting

of the Edgar Allan Poe Club was held at 530 North 7th Street, Phil-

adelphia, where Poe, Virginia, and Virginia’s mother, Maria Clemm,

lived in 1843. (Today it is a National Historic Site.)

A certificate commemorating the event was signed by a participant

who was an early collector of Poeana, as well as

the then owner of the house, Richard Gimbel. Tane

owns that certificate. She got it on eBay.

Tane has not neglected artists’ renderings of

Poe-inspired images. They constituted a rich part

of the show, and many were reproduced in the cat-

alog. One of them is from a series of woodcuts by

Antonio Frasconi (1919-2013), published in 1959

in

The Face of Edgar Allan Poe

with a text by

Charles Baudelaire. Another is a lithograph of a

raven’s head by Édouard Manet for his illustrated

book of

The Raven

, titled in French

Le Corbeau

.

Published in 1875, the book, with a translated text

by Stéphane Mallarmé, is signed by both men.

On the afternoon I visited Tane in her apartment,

she told me the show would be called “From Poe

to Pop.” In the end, the Grolier Club thought that

title didn’t reflect the importance of this nearly

500-object show or its full depth and breadth. “So

we had a brainstorming session,” Tane recalled,

“and ‘Evermore’ came out.”

The original “From Poe to Pop” phrase was

retained as the title of one of the show’s final chap-

ters. That was all about kitschy Poe. A T-shirt with

an image of Poe captioned “Dropout” says every-

thing we need to know about how Poe’s popularity

has made him a hero in circles other than literary

ones. The same goes for the skateboard of Tane’s

fellow collector Peter Fawn. On the board’s deck is

an illustration of a raven pecking the top of Poe’s

head, which is opened like a lid to reveal the pink

squiggles of his brain.

If asked to choose my favorite item in the show,

I would say Tane’s photograph of the place where

Poe is thought to have composed

The Raven

. It is

an image of a farmhouse in a rural setting. In fact,

it is present-day West 84th Street. Poe lived there

in 1844 (

The Raven

was published in 1845) when

what is now the Upper West Side was far from the

heart of the city. It’s not a particularly rare image,

but it provides the kind of context that makes this

collection unique. That quality is also what made

Tane’s telling of Poe’s story in an exhibit so appeal-

ing. Now that the show is over, the same quality is,

likewise, the reason why the catalog makes such a

satisfying permanent record.

Of collecting Poe over these last nearly 30 years,

Tane told another interviewer, “I love doing this.

I love putting all the pieces together, and there’s

still so much more to learn.” She has, however,

moved on a bit to Walt Whitman. The bicentennial

of his birth is May 31, 2019, and she hints that she

is gearing up for it. “I had the opportunity to buy

some major Whitman pieces from someone. I have

the good pieces. I need some fillers,” she said.

In the more immediate future, Tane is under-

taking another Grolier Club exhibit of items from

her collection, this time one that is not Poe-cen-

tric. Scheduled for September to November 2016,

the as-yet-untitled show will explore 19th-century

American authors’ relationships with each other

and with their publishers. For more information,

contact the Grolier Club through its Web site

(www.grolierclub.org).

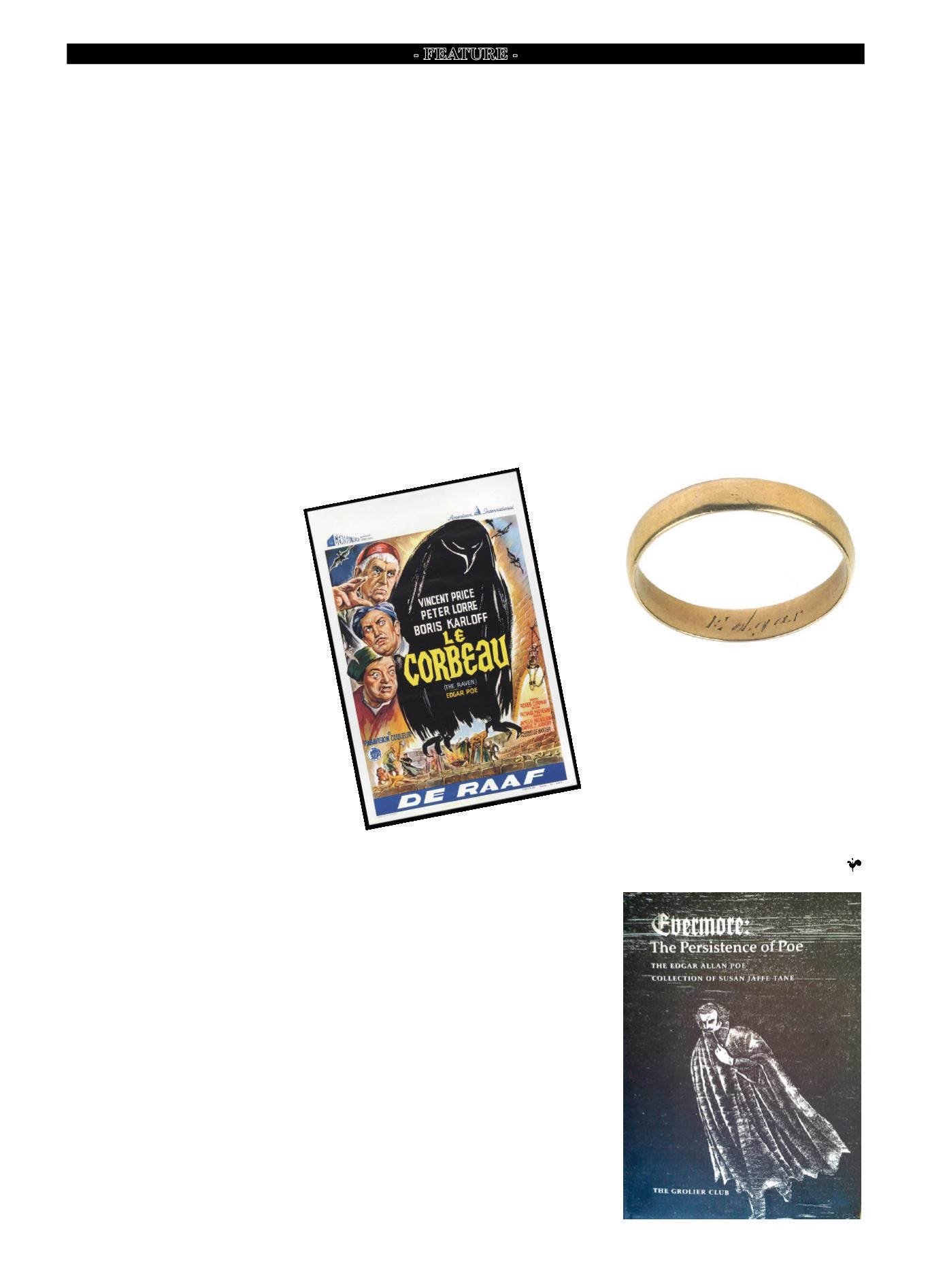

This gold engagement ring was given by Poe to Sarah

Elmira Royster in 1849, shortly before he was struck with

whatever ailment killed him. It is engraved “Edgar.” The

ring was sold along with other items and accompanying

documents to Tane for $96,000 at a Profiles in History

sale in December 2012. The cache came directly from Poe

descendants. As a teenager, Royster became Poe’s first

love, but her father’s disapproval ended the relationship

while Poe was at the University of Virginia, where he did

no better than he had at West Point. She married, had

children, and was widowed in 1844. Poe came back into

her life four years later; they were engaged but never

married. Photo credit: Robert Lorenzson.

Dust jacket of

Evermore: The Persistence of Poe:

The Edgar Allan Poe Collection of Susan Jaffe

Tane

. It was published in hardcover by the Gro-

lier Club in conjunction with the exhibit of the

same name, on view at the club from September

17 through November 22, 2014. The book is 208

pages and fully illustrated. Its price is $60 plus

shipping and handling from Oak Knoll Books

(www.oakknoll.com), exclusive distributors of

Grolier Club publications. The portrait of Poe

on the cover is a woodcut by Antonio Frasconi.

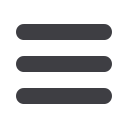

Belgian poster for Roger Corman’s

1965 film of

The Raven (Le Corbeau).

The poster measures 21¼" x 14". Cor-

man’s popular series of Poe adaptations

“take great liberties with their source

materials,” the

Evermore

catalog states.

Photo credit: Robert Lorenzson.